|

Field experimentsMiller’s role will be to understand the relationship between the benthic fauna and the sediments on which and in which they live. She wants to know how they churn and affect the sediments, which is a function of how many animals are present and how fast the sediment accumulates. Most of the sediment cores drilled in the region — such as from the recent ANDRILL program and the older Cape Roberts project “We’re actually doing a direct approach,” she explained. “We’re collecting animals that live there, putting them in constrained little aquaria with sediment, and we’re looking at how they mess it up.” Divers will also put out sediment traps on the seafloor to see how much sediment accumulates during the course of the fieldwork. Some traps will remain out for two years until the project resumes in 2010. More on the Web

The aquariums, which are only about 2.5 centimeters wide, include screens that allow ocean water to move through the chamber. “It’s basically a little microcosm of the natural world,” Miller said. At the end of the season, divers will collect the aquariums, which the scientists will then freeze and return to the laboratory, where they’ll X-ray the tanks to detect any churning of the sediments by the animals. Then they can compare the results with X-rays taken of sediment cores. “We’re just unclear as to the extent by which that [bioturbation] process is going on and has been going on,” Miller said. “It looks like it’s not too extensive in the cores in the ANDRILL and Cape Roberts projects.” Walker will use techniques developed for a long-term experiment in the tropics that she’s involved in called the Shelf and Slope Experimental Taphonomy Initiative (SSETI)

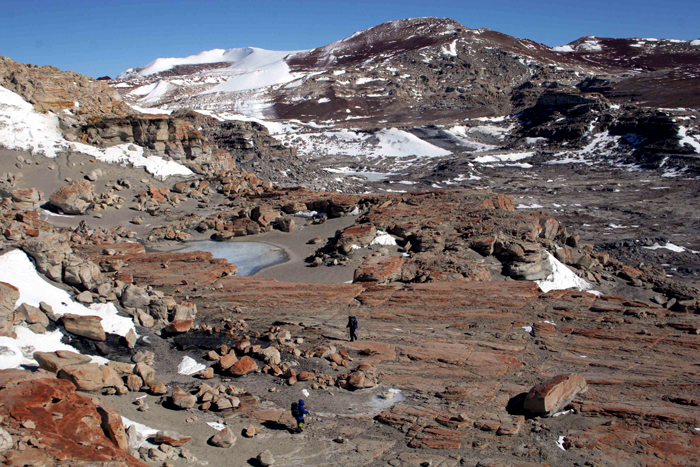

Photo Credit: Sally Walker

Sally Walker in the field — just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco.

“Just like a skyscraper is built differently than a ranch-style home, animals do that, too,” Walker said. “I would expect a spectrum of dissolution [rates] in the short term and the long term.” For example, forams build complex shells of calcite that seem to outlast a snail shell of aragonite, according to Walker. She will also use instrumentation employed by coral reef researchers, a water-quality-monitoring sonde, to measure water temperature, acidity, nutrient levels and other parameters to constrain the conditions under which the decay occurs. More generally, the scientists will track the relative abundance of species in the underwater region. “Even in a place like Explorers Cover [there are] components of the fauna that are not very well known at all,” Miller noted. “The implications of this project are greater because of the diversity of people involved,” she added. NSF-funded research in this story: Sam Bowser, New York State Department of Health, Award No. 0739583 |