|

That's heavyGravity helps measure subglacial lakesPosted April 24, 2009

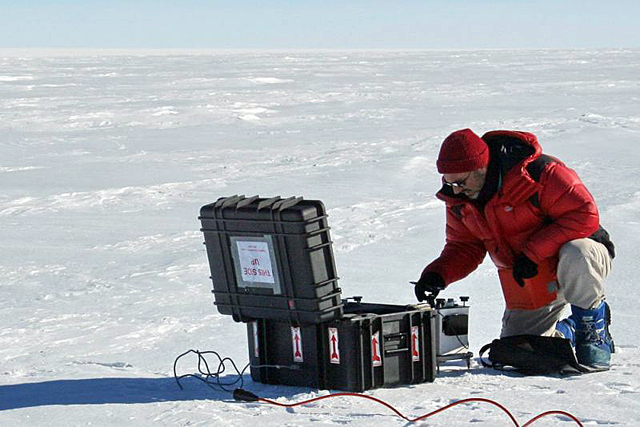

[Editor's Note: Ted Scambos One of the new geophysics studies we’re doing this year on the Recovery Subglacial Lakes side traverses is measuring gravity. The Earth’s gravity varies a tiny bit from place to place, depending mostly on elevation, latitude and the column of rock, water, or ice below a given point. The goal of our gravity measurements is to try to map the thickness of the water layer in the lakes. To do this accurately, we need three things — an accurate elevation profile, a good measure of the ice thickness, and very precise gravity measurements. The signal that would indicate water (of at least 10 to 20 meters thickness) would be lower gravity than expected once the elevation and ice thickness are accounted for. The ‘missing mass,’ making the gravity too low is water — instead of rock — just below the ice. The gravimeters are amazing pieces of engineering. They are actually based on a design that has been around since the 1960s — a very precisely made spring, very delicate and with many turns, is connected to a complex lever and weight system inside the meter. The lever system amplifies the tiny stretches or contractions of the spring. The inner chamber is kept at a constant temperature of about 50° C (about 140° F) and it has to stay perfectly constant even in Antarctic conditions. But, if set up properly, the system can measure gravity differences between two sites to about five part per billion of the Earth’s average gravity level. We have a special insulated and heavily padded box to keep the two gravimeters, and it has a power plug on the outside so that we can keep the internal heater and thermostat system running at all times. So far, the data look very promising. Supplemented with ice thickness data from the radar profiles and elevation data from precision GPS logging, they should allow us to map the lake depths — even though the water is more than a mile and a half/two kilometers below us. Return to main story: IPY Traverse. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |