Page 2/2-Posted February 24, 2012

Taylor Valley may once again fill with giant lakeFor scientists like Diana Wall “All of us are seeing much more connectivity between the glaciers, the steams, the lakes,” Wall said. “It’s like one big hydrologic cycle, and all of a sudden it’s tying everything together.” Flooding hasn’t been restricted to the Taylor Valley. The Onyx River in Wright Valley to the north has flowed at speeds upwards of 700 cubic feet per second in recent years. “That’s a real river, which in a very cold place like this, represents a lot of melt,” McKnight said.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Scientists John Priscu checks on an experiment looking at changes in lake biogeochemistry.

Photo Credit: John Priscu/Antarctic Photo Library

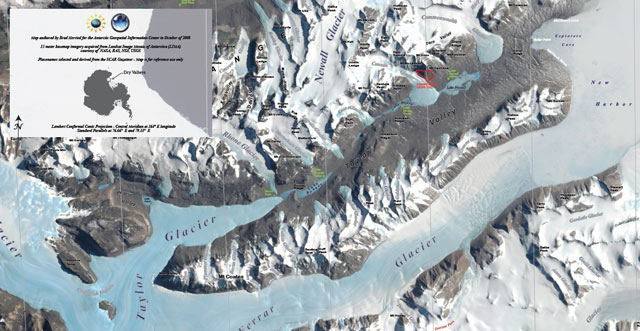

Scientists set up a tent on Lake Bonney for research.

A water-dominated system would not just affect soil biodiversity, but also biodiversity in the lakes. Priscu predicts that if the current trends continue, the biogeochemistry of the entire ecosystem would change as the water engulfs more of the valley. In 100 years, Lake Fryxell would merge with Lake Hoare. In two centuries, Lake Bonney would flow east and coalesce with Fryxell and Hoare. In less than a millennium, the lake would fill the valley and drain into McMurdo Sound. “When they starting merging again, the biodiversity is going to smear out,” he said. “We’re going to lose these unique organisms.” It wouldn’t be the first time such a lake existed. Scientists have suggested that a proglacial lake, formed by the retreat of a glacier, filled the valley to a much larger extent at the end of the last ice age. It’s also not the first time rising lake levels have prompted a field camp move. A new facility was built at Lake Hoare in the mid-1990s when it became the main gateway camp for the LTER program. The original camp from the 1980s was small — just a single lab, a storage building, and a Korean-era building known as a Jamesway that served as the kitchen and social center of the facility. However, the old camp wasn’t removed until this past field season, as the lake began to rise again in earnest over the last couple of years after idling for nearly a decade, according to Haywood. “It was obvious that it was time to move it,” he said. The Jamesway, which had still been used for storage, was relocated to the current camp onto a timber foundation. “The ‘newer’ Hoare camp should be fine for quite a few years to come,” Haywood said. For more than a decade, from the late 1980s into the early 2000s, the Dry Valleys were actually cooling. The LTER researchers even published a paper in the journal Nature Priscu said that the cooling trend has been shown to be influenced by ozone depletion in the stratosphere, which researchers believe affected circulation patterns in the lower troposphere. Basically, a cold high-pressure system settled over the region during the period of cooling, shielding it from warmer air. But as the ozone layer slowly heals, the atmospheric patterns appear to be returning to pre-ozone trends, according to Priscu. That means more grey but warmer days ahead. “Things are changing. They’re changing right in front of us,” Priscu said. “What we’re studying is pushing us out — we’re studying climate change.” NSF-funded research in this story: Diane McKnight, University of Colorado at Boulder; John Priscu, Montana State University in Bozeman; and Diana Wall, Colorado State University; Award No. 1115245 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |