Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

|

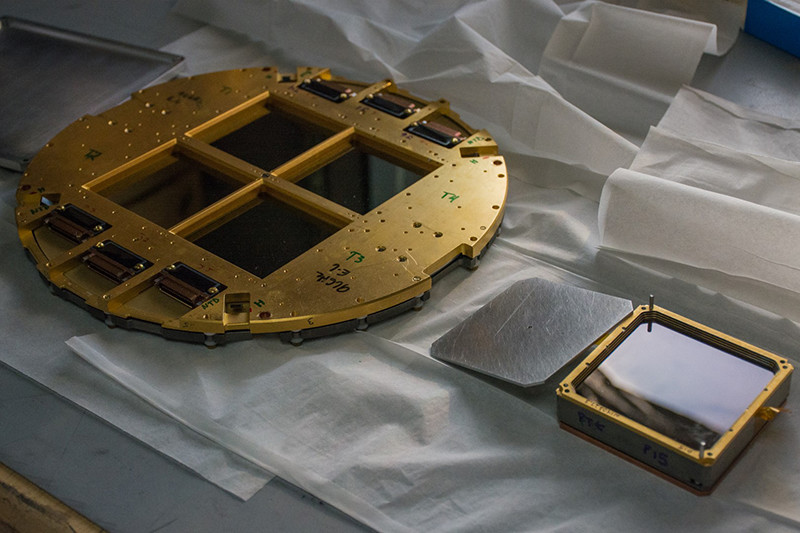

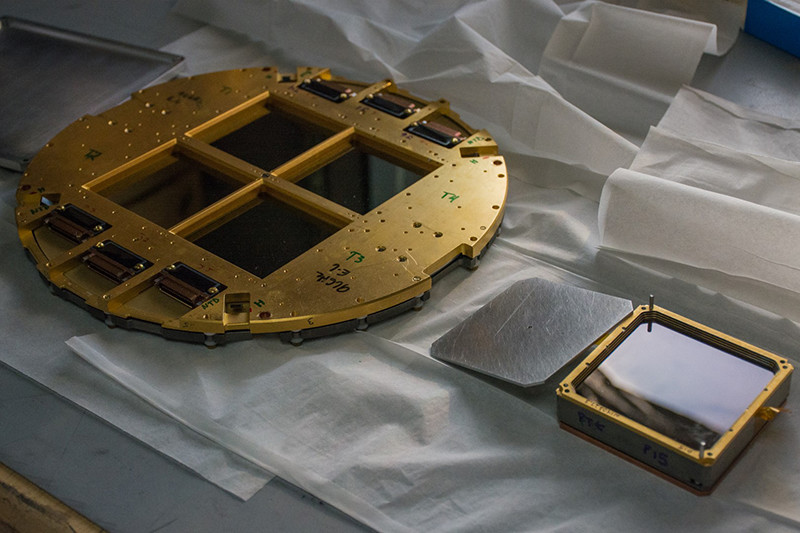

The focal plane (left) is made up of four smaller detectors (right) with thousands of pixels sensitive to the

dim microwave radiation of the CMB.

|

Searching for Inflation (cont.)

By Michael Lucibella, Antarctic Sun Editor

Page 2/3 - Posted August 1, 2016

“There is a leading theory called inflation that attempts to explain the initial conditions of the universe; how it wound up as big and as smooth, and as geometrically flat as it observably is,” Kovac said.

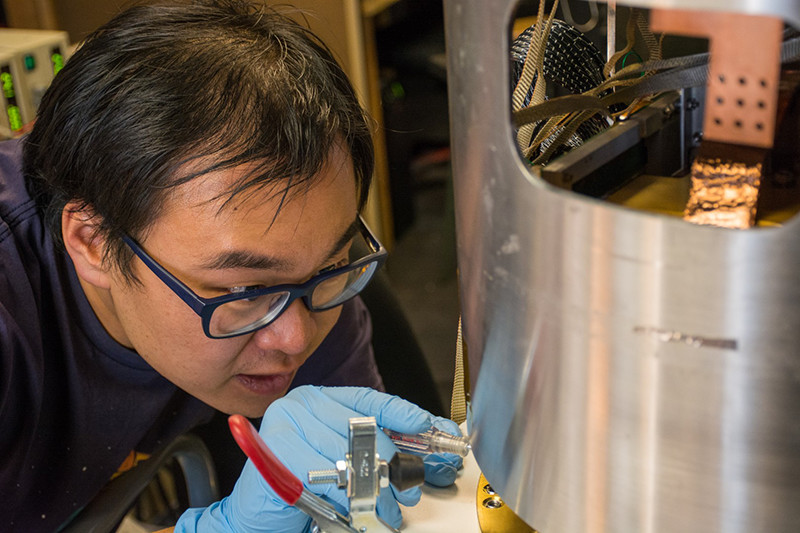

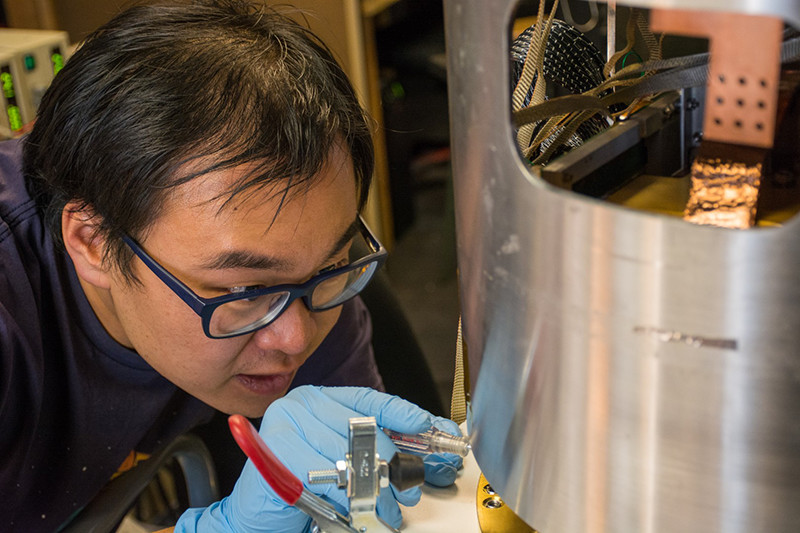

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Howard Hui works on installing a new focal plane into one of the Keck Array’s receivers.

When the universe was still smaller than an atom, it was almost perfectly smooth, essentially because everything in it was evenly distributed throughout and still close enough to interact with everything else. At such small scales the universe would have been governed by the weird laws of quantum mechanics where uncertainty reigns and particles can blink in and out of existence.

Scientists theorize that shortly after the Big Bang, the universe went through an intense period of high-speed expansion driven by quantum forces. For roughly 1 x 10¯³² of a second, the universe expanded faster than the speed of light from its subatomic size until it would have been almost big enough to see with the naked eye. In that instant, the universe grew a hundreds trillion trillion times its original size. Scientists think that this intense inflation also expanded the universe’s original near-perfect smoothness across the entire cosmos.

“What our telescopes are doing is looking for evidence that can test this leading theory of inflation, by checking for one of its key predictions,” Kovac said.

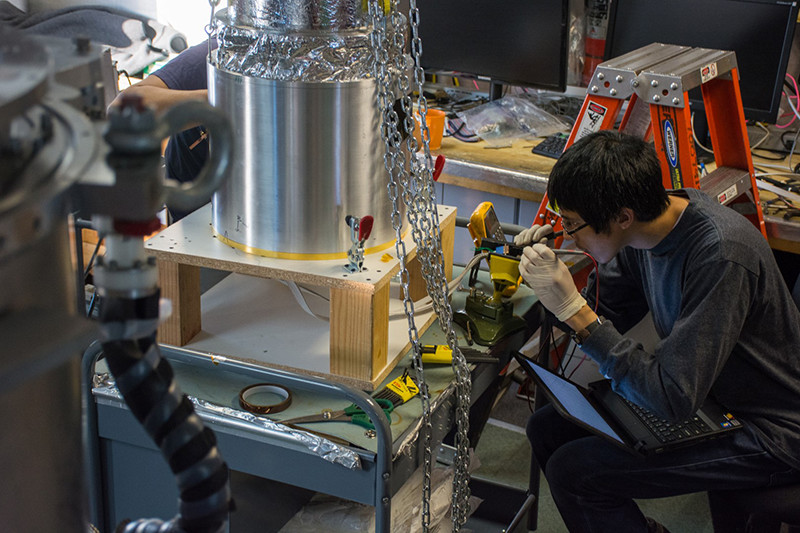

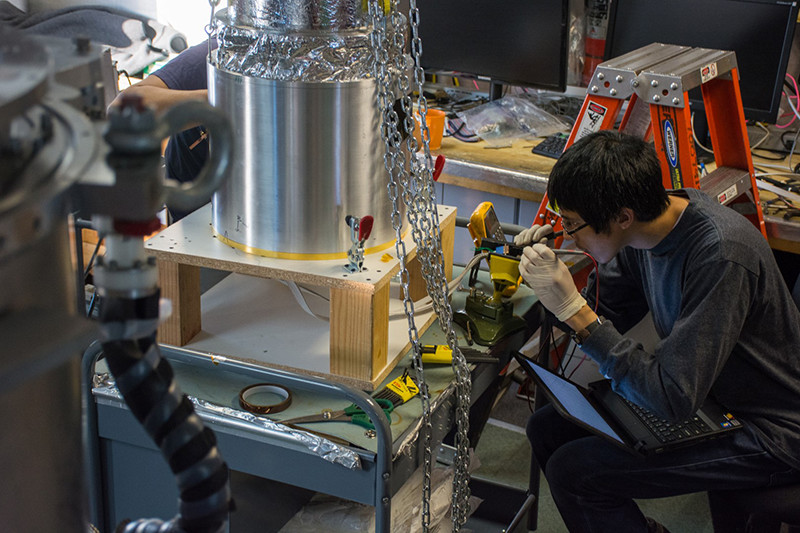

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Kirit Karkare checks the electrical connections on the Keck Array’s receiver.

They’re looking for traces of it in the cosmic microwave background, specifically what are called B-mode polarization patterns, or B-modes for short. They’re subtle, swirly fluctuations imprinted on the CMB by inflation.

As the universe violently expanded during inflation, it produced powerful gravitational waves, essentially ripples in the fabric of space-time. As these waves traversed the then-tiny universe they expand and contracted the space that they passed through.

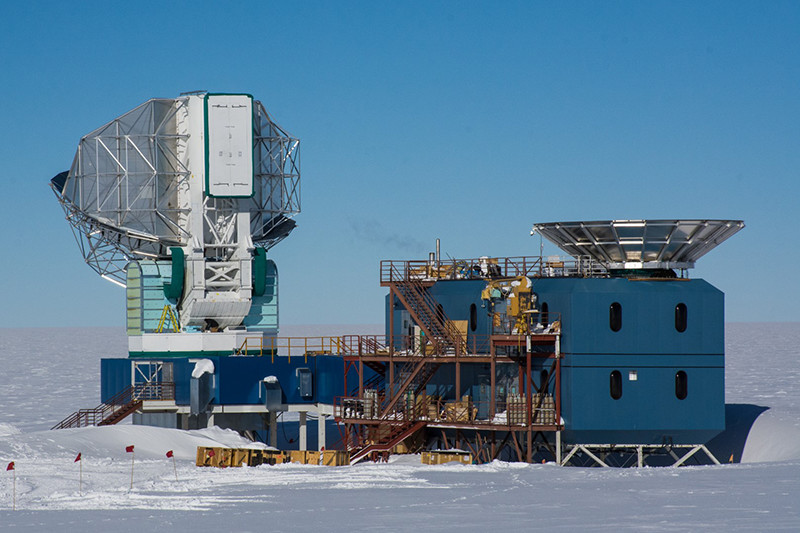

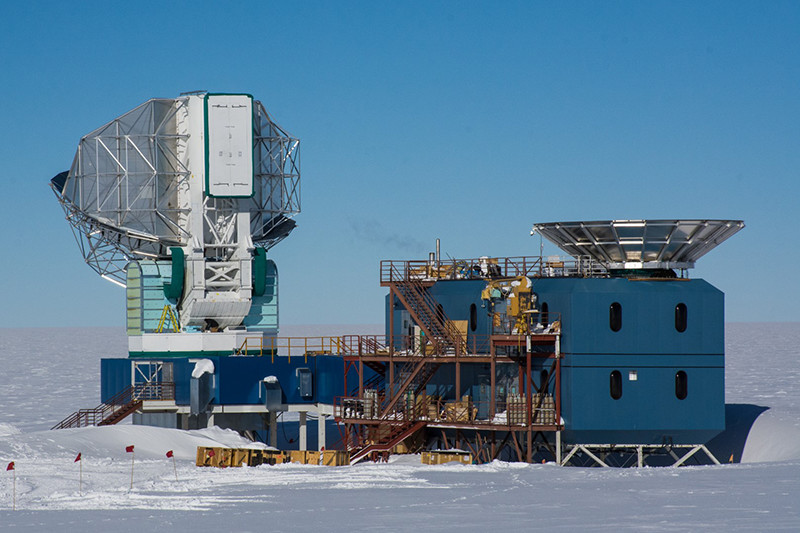

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Shrouded inside the inverted silver cone, the BICEP3 telescope is housed a short distance away from the Keck Array.

“Modern physicists have long believed, that general relativity and quantum mechanics must be compatible and ultimately that there must be a consistent quantum theory of gravity, and yet producing that theory in detail has been a project that’s been ongoing for the last 50 years in theoretical physics,” Kovac said. “The observation of quantum generated gravitational waves would be unique evidence that there is indeed a quantum theory of gravity, that gravity is a quantum phenomenon.”

The discovery wouldn’t tell scientists exactly how the two theories tie together, but it would be the first concrete proof that they do.

Finding these swirly B-modes hidden in the CMB would be a major advance for theoretical physics. However, there’s more than just the cosmic microwave background in the skies. Floating throughout the galaxy are wisps of cosmic dust that can emit similar signals, and they’ve proven to be unexpectedly troublesome in the past.

In March of 2014, at the end of the run of their previous telescope BICEP2, the team announced that they had made a potential discovery.

Previous

1

2

3

Next