The Prehistoric Forests of the Frozen ContinentPosted June 30, 2017

Paleontologists uncovered the fossil remnants of the oldest forest yet discovered in Antarctica.

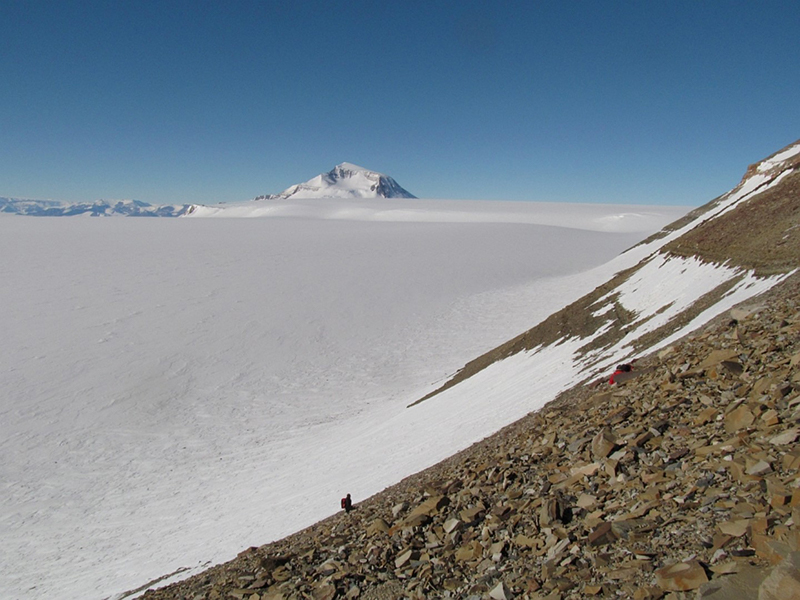

Photo Credit: Anne-Laure Decombeix

Erik Gulbranson and mountaineer Jonathan Hayden look at a small fossil tree.

“In this forest we found at minimum 13 stumps in place,” said Erik Gulbranson, of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “There are many more but they are either covered in all of this scree or covered by these large snowy drifts.” At about 270 million years old, the stumps come from an extinct species of tree known as Glossopteris. The fossils promise to offer paleontologists insights into the prehistoric climate and ecology of Antarctica, and the dramatic ecological changes that were about to sweep across the continent. These trees pose an interesting question for researchers. While most other continents around the world drifted far distances across the planet’s surface, Antarctica has remained largely in the same location. “Antarctica at that time is still around the South Pole, so you’re talking about plants that existed in an extinct biome. They’re polar forests,” Gulbranson said.

Photo Credit: Anne-Laure Decombeix

With the Twin Otter plane in the background, Erik Gulbranson carries a bag full of ash samples that the team will use to date the layers with fossil plants.

The researchers were looking for the remains of ancient plants near the southern tip of the Transantarctic Mountains. It’s an ideal location to recover specimens around the Permian-Triassic extinction event, a period of time about 252 million years ago when nearly 90 percent of the Earth’s species suddenly died off. “It was probably the greatest mass extinction ever,” said John Isbell of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, of the National Science Foundation-funded project. NSF manages the U.S. Antarctic Program. Fossils from around the time of this global cataclysm have been recovered from across the globe. However, because of its remote location, scientists have only begun to explore what Antarctica might be able to tell them about this mass die-off. “Most everything that has been done has been done by looking at stuff in low latitudes, so we really need to understand what’s going on at high latitudes to make a complete picture,” Isbell said. “Antarctica is the only place that you can go to get that polar view of the world.” Scientists hope to learn more about the climate and ecosystems that once existed on the now-frozen continent by studying what kinds of trees and plants lived in the region. Focusing in on the time of the great extinction between the Permian and Triassic periods lets researchers better understand why some species go extinct and while others manage to pull through. The fossilized forest helps them establish a sort of ecologic baseline to compare what and exactly how much changed over the tumultuous transition. At the end of the Permian Period, 252 million years ago, the planet was a much different place. “The Earth at the time, instead of having many continents like we do today, there was one large supercontinent, Pangea,” Gulbranson said. “A sector of that, the southern sector, is referred to as Gondwana, and that included the continental masses of South America, Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Australia and Antarctica.” The climate was dramatically different as well. Today most of Antarctica is buried under thousands of feet of ice, but the continent wasn’t always a frozen desert. Over hundreds of millions of years, the continent drifted between its current ice-covered state and more temperate climates. “Roughly 300 million years ago, Antarctica was glaciated much as it is today,” Gulbranson said. “Over the intervening basically 45 million years or so… those glaciers waned and melted away and transitioned into a very lush, forested ecosystem.” Rudolph Serbet of the University of Kansas added that months of total darkness during winter would pose unique challenges to the plants and animals living in such a polar forest. “We don’t have any living analogies to that kind of climate where a plant can stay in darkness for so many months,” Serbet said. “How can they stay in darkness for six months? Did they lose all of their leaves? And if they did then what was the food supply for the animals that were there that are vegetarian?”

Photo Credit: Anne-Laure Decombeix

The white rocks at the foreground of the rock outcrop are ash layers that allow the researchers to accurately date the to the fossil plants.

Five science researchers traveled to Antarctica to search for the fossil remnants of these ancient ecosystems along an area of the southern Transantarctic Mountains known as the McIntyre Promontory. They established their base of operations at the Shackleton Glacier field camp, and flew to their survey sites to hunt for fossil remains. Originally, they had hoped to set up camp at a different location--Alfies's Elbow in the Cumulus Hills--and travel to numerous sites using snowmobiles over two months. However, over the winter, the ground conditions around the region changed unexpectedly to the point where a plane couldn’t land safely to unload all the supplies they would need for their project. After a number of other sites failed to pan out, their planned two months in the field became a handful of daylong trips to exposed rock of similar age and composition along the McIntyre Promontory. Despite the limited time the team had at the fossil beds, they returned with some significant new findings. “We were only able to visit one site four times, and in those four trips we discovered three new things,” Gulbranson said. In addition to the oldest forest discovered on the continent, they found also a number of smaller plant fossils mixed in with the forest, and ash left over from at least six volcanic eruptions from the late Permian and early Triassic periods. “The ash is important, and it’s actually the reason why this region is important for us,” Gulbranson said. “It’s really exciting to see them here, because what also comes out in the volcanic ejecta are special minerals called zircons. And zircon is fantastic for us because it incorporates a lot of radiogenic uranium when it crystalizes in the melt.” The uranium in the volcanic ash is key to be able to accurately date the embedded fossils within. Because it’s radioactive, uranium breaks down into other radioactive elements at a predictable rate. These other elements do the same until they reach the element lead, which is stable, and the decay chain ends.

Photo Credit: Anne-Laure Decombeix

Rudy Serbet sorts through a number of plant fossils brought back to Shackleton Camp after a daytrip.

“We can come by 200 million years later and extract those zircons and simply try to count how much lead has been evolved from that uranium that was initially there, and that allows us to get the precise age control on this,” Gulbranson said. Altogether, the team found six eruptions, which will go a long way to helping pin down exactly when these Glossopteris trees were growing. This precision is important because recent fossil finds surprised scientists when they seemed to indicate that Glossopteris trees may have persisted through the massive extinction event at the end of the Permian period about 252 million years ago. “What’s tantalizing about this site is that 12 years ago or so, a group here found evidence of a Glossopteris plant in stratigraphy that we think is Triassic,” Gulbranson said. “That potentially suggests it did not go extinct, or it persisted across the boundary.” Intermingled amongst the trunks of the Glossopteris trees were the fossilized remains of another plant species, ones that were close relatives of today’s grass-like horsetails often found in wetlands throughout the world. It’s another important find for the team, as it reveals a more complete picture of the ecosystem that made up these ancient forests. “We don’t have a good idea of the understory of the forest that these trees were forming,” said Anne-Laure Decombeix of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Montpellier, France. “This gives us an idea of what was growing lower in this forest. It’s the first time we found this association. We also found seeds and other types of leaves.” There’s a lot that the researchers hope to learn when they return to the fossil sites. ”The current interpreted age of the last appearance of Glossopteris fossils in the Shackleton Glacier region is Late Permian. However, a specific age is unknown,” Isbell said. “Therefore, further work on these strata may provide important clues as to the evolution and demise of this important fossil flora." The team is excited to be returning this upcoming season and continuing their search for more fossilized remains. The Shackleton field camp will be equipped with helicopters during the 2017-18 season to help transport them and their field equipment to their planned campsites. They’re planning to stay out in the field longer and hope to return with many more specimens. “Getting out into the field and camping, you have a lot more time to find the different areas, excavate the sites that you want to,” Serbert said. “What’s nice about a camp put-in is even if the weather goes down and you can’t travel, you’re still at a camp where you can still go up and collect data.” In the meantime, the team is continuing to catalog and study the fossils they brought back. They’re working to better understand the ancient history of the continent and also glean insights into what the future may hold as current climate change continues. “There’s also a lot of questions for the future, [like] how are plants going to react if the climate keeps changing,” Decombeix said. “We can look at a place where we can see back into the past, and maybe get some clues.” NSF-funded research in this story: Edith Taylor of the University of Kansas, Award No. 1443546. |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |