Byrd historyIGY station, field camp has supported West Antarctica science for more than 50 yearsPosted June 12, 2009

“Snow melter shoveling is one of the exciting experiences you get at only small inland stations, so consider yourself one of a select group.” — Your Stay at Byrd Station 1970-71 That little excerpt from the 10-page New Byrd Station guide from more than 35 years ago is a light-hearted reminder that life in Antarctica’s vast backyard is far from the comforts of home — or even the relative luxury of McMurdo Station At 80° south latitude and 119° west longitude, it’s not a spot on the world map suitable for a family vacation. The Navy personnel charged with establishing the first Byrd Station during 1956-57 for the International Geophysical Year (IGY) More on Byrd

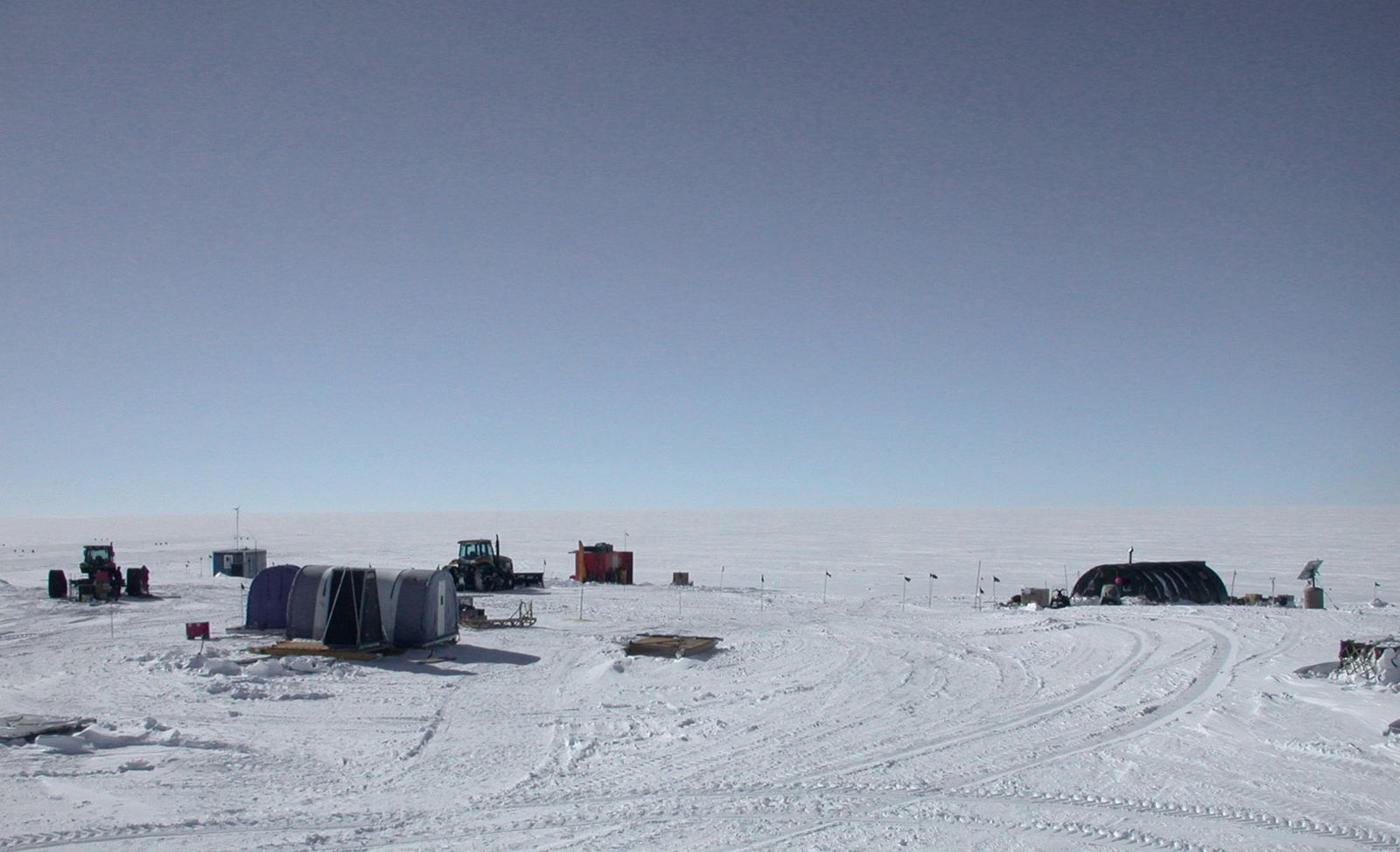

Named after the famed polar explorer Rear Adm. Richard E. Byrd Jr., the new station was something of a hurried, ad hoc effort that first season when the military officially commissioned it on Jan. 1, 1957. A tunnel system connected the station’s five main buildings, but most of the supplies for the underground corridors never arrived. So the men improvised, welding together empty oil drums to serve as vertical columns for the tunnel framework. The first winter-over crew of scientists and Navy personnel had enough food, if the variety was limited, but a short supply of libations, including a ration of only 10 cans of beer per person for the entire season of darkness. Not all was deprivation. Charles Bentley, a scientist who spent the first two winters at Byrd Station, had his collection of chamber music with him. On his way north after 25 months on the Ice, he lent the records to an incoming seismologist, who promised to return them. “He never brought them back,” said Bentley, who at 78 returned to Antarctica in 2008 for the WAIS Divide ice-drilling project. “My records are still out there. I always had the idea that I could go back and get them.” [See related story: Practically home.] No one is likely to see them ever again. The first station was only used for four years because the weight of snow threatened to collapse it. Construction of a second research station began in 1960, about six miles from the original location. Prefabricated buildings with steel “wonder arches” were lowered into man-made trenches and manually covered with snow, a concept first developed and tested in Greenland by the U.S. Army. Commissioned on Feb. 13, 1961, New Byrd Station was located underground except for some scientific structures. Tunnels connected the stations’ various facilities, which served to support the largest inland scientific program at the time. New Byrd Station outlived its predecessor, lasting for about a decade. However, equipment vapors, human breathing and various other sources caused rime to form on the inside, and over a period of several years, the structures buckled from within. In 1972, the station was redesigned and moved to the surface. It was then used as a summer-only field camp. MemoriesPatrick Haggerty is the Research Support and Logistics Manager in the Arctic Sciences Division of the Office of Polar Programs at the National Science Foundation Part of the house mouse duties — common housekeeping tasks shared by all at the station — included roof maintenance, he said. “[We spent] a day per week with an electric chain saw cutting snow blocks from over the buildings (standing on the roofs), and dropping them over the side into a snow melter. Hot water from the electric snow melter would then be drained into a hole in the bottom of the tunnel.” Recreation at New Byrd Station was “self-made.” There was a library and club, which contained a pool table and BYOB bar. Byrd Surface Camp carried on support for science in West Antarctica in succeeding summers, albeit scaled down from the heyday of the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1970s and 1980s, the camp primarily supported the new Siple Station at the base of the Antarctic Peninsula as a waypoint for flights, according to Dave Bresnahan, a long-time U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) “Flight time, round trip, to Siple was 11 hours via LC-130 from McMurdo,” Bresnahan said. Byrd Station essentially served as a gas station to increase the amount of cargo each plane could carry between McMurdo and Siple. The standard routine, he said, was to fly direct to Siple from McMurdo, offload the cargo, and then stop at Byrd for additional fuel before returning to McMurdo. “For every three flights to Siple Station we needed two flights to Byrd to position fuel at the camp,” Bresnahan explained. “So, if we had 75 flights planned for Siple, we had to make 50 to Byrd just for fuel for the return flights.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |