Getting a liftNASA upgrades ground station at McMurdo as new missions come onlinePosted March 25, 2011

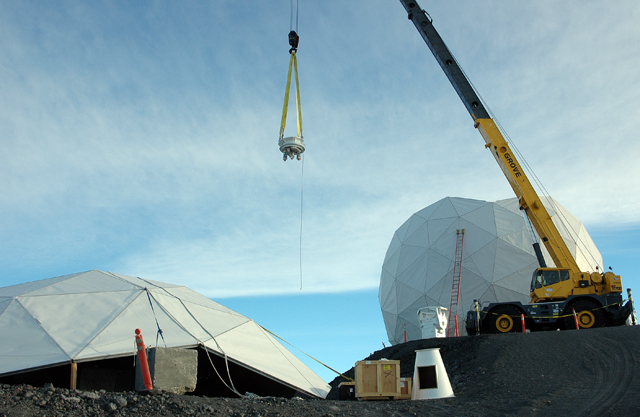

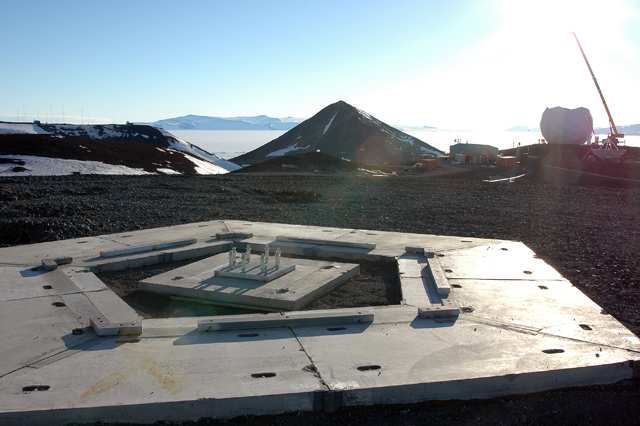

Racing against the wind is never a good bet in Antarctica. But for a group of engineers, construction workers and technicians doing a major upgrade to a 10-meter antenna housed in a golf ball-shaped dome on a hill overlooking McMurdo Station Only about six weeks after the team uncorked the radome — pulling out and replacing or upgrading tons of equipment — the refurbished NASA McMurdo Ground Station (MG1) antenna system acquired its first data from a European weather satellite in January as part of a new international collaboration. For a few tense days in December 2010, the entire project was hanging from the end of a 75-ton capacity crane. “Hypothetically, we could have lost the radome and put the [ground] station out of business for a long time,” said Kevin McCarthy, an engineer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center The antenna and protective radome were originally installed at the U.S. Antarctic Program’s The MG1 site has taken on a number of other missions over the years as part of NASA’s Near Earth Network “I think we’ve done an excellent job over the last 16 years of supporting missions out of McMurdo,” McCarthy said, though adding that over the last five years the antenna has experienced more outages. It was time for an overhaul, especially after NASA and NOAA MetOp-A is the first in a series of three European meteorological operational satellites that will serve as the space segment EUMETSAT Polar System. The MG1 site, thanks to its high latitude, is well located for downloading mission data from MetOp-A, delivering environmental data to U.S and European weather services twice as fast as they receive it today. The MG1 site will also support future MetOp-B and MetOp-C satellites over the next 15 years. “We thought it was prudent to do a complete overhaul of the antenna system,” McCarthy said. But first the NASA engineer and his 17-member team — with the support of McMurdo Station staff — had to replace the majority of the electronics systems in the ground station, as well as the pedestal that held the 10-meter dish. The laundry list for the lift operation seemed daunting: Unload the new antenna pedestal and train assemblies from their shipping containers; remove the radome lid; pull the 10-meter antenna dish; de-stack the antenna pedestal; and then put all of the new and refurbished equipment back. Finally, re-cork the radome. The catch was that winds could not be more than 12 to 20 miles per hour, depending on what piece of equipment was dangling in the air. The lid of the radome required the most care, as anything more than a gentle breeze could turn it into a sail. Additionally, without the lid in place, the radome’s structural integrity was compromised. Shifting into a night schedule when the winds are historically at their lowest, the NASA team took about three days to crack the radome open, perform its work, and recap the structure. One day was lost when the new assembly didn’t quite fit together correctly. Winds stalled completion of the work for a second night. “We knew the wind was going to be a challenge from the beginning,” said David Huntsman, senior project manager for Raytheon Polar Services It was up to Huntsman and the various work departments at McMurdo Station to make sure the NASA team had the support it needed to get the maintenance job done on the ground station. That involved another long laundry list of tasks, including constructing a warming hut out of milvans for people working long hours outdoors, as well as a restroom facility at the site, along with a whole set of stairs from the electronics building to the radome, a steep and slippery path in seasons past. “The wood for the stairway came from the old bowling ally floor joists that we demoed last year,” said Mike Ebel, RPSC construction coordinator. “We were able to retrieve it from the wood pile before it got chipped up. Weather was a very big factor with the winds at 30-plus knots and wind chills below zero.” Added Huntsman, “Everyone in [McMurdo was] very supportive.” And there will be much more work to support with a second McMurdo ground station, dubbed MG2, planned for installation by 2014 for additional NASA missions. In the bigger picture, the NASA ground stations support an umbrella project called Joint Polar Satellite System NOAA, NASA and the U.S. Air Force are working on various components of the new U.S. weather and climate satellite system. JPSS is the NOAA and NASA portion of the program, while the Air Force is working separately on the DWSS. Both U.S. satellite systems will share a network of ground station sites called the Distributed Receptor Network (DRN). McMurdo is one of 15 locations for DRN, and this season it became the first one worldwide to complete an installation. The McMurdo site is a key linchpin of the ground system that will receive the data from the new U.S. polar-orbiting environmental satellite system. Its high-latitude location will nearly halve the time it takes environmental data from outer space to get to end-users around the world. A second DRN ground station will be installed next year near the MG1 and future MG2 site above McMurdo Station. All that data bouncing from space to McMurdo and back again to satellites necessitated a major upgrade to the station’s communications facilities at nearby Black Island. The outbound stream of data by the NSF and various MGS and JPSS antenna systems will have 60 megabits (Mbps) per second of bandwidth to use. The project is especially a boon to the USAP for the marked increase of inbound bandwidth. The next upgrade will double inbound data — particularly for the heavily trafficked Internet — from 10 Mbps to 20 Mbps by January 2012. Some of that bandwidth will be used to control the antennae sites from the United States with new commands when necessary, according to Huntsman. “We’ll have dynamic sharing, so that when they’re not using it, we can burst up to 20 megabits,” Huntsman said.

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |