Page 2/2 - Posted August 27, 2010

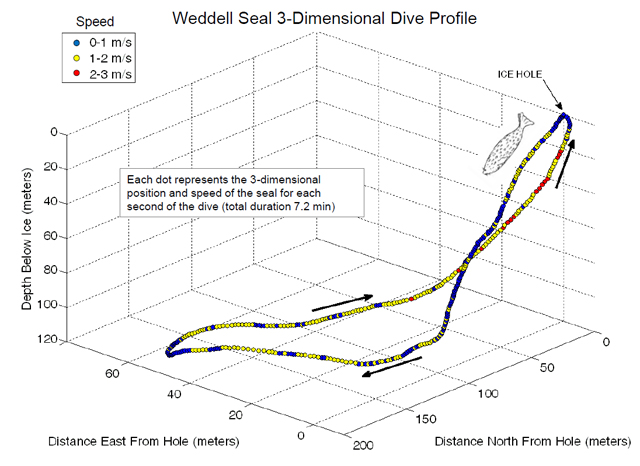

By a hairIn spite of their work on other critters, the focus of the group remains the Weddell seal. The video data recorders glued onto the seals’ fur collect a variety of data that allow the researchers to create three-dimensional dive profiles, which they can then use to interpret the animal’s behavior. The data include depth, compass bearing and number of flipper strokes. The recorders also report on environmental conditions such as temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen in the water. “It’s a suite of variables that allow us to look at diving and swimming performance, as well as the animal’s immediate environment in three-dimensional space,” Davis explained. From the videos and other data, the seal biologists have learned a great deal about Leptonychotes weddellii behavior during the daylight hours. For example, after dropping away from a breathing hole in the ice, the seals become negatively buoyant in the first 30 to 50 meters, allowing them to dive with little effort as they make a “meandering descent,” according to Davis. Davis said he believes that the seals rely primarily on vision when light is available, possibly detecting the silhouette of fish from below when they go in for a kill. “They’re probably backlighting their prey, which means they’re relying on vision,” he said. “They have exquisite low-light vision. We’re pretty convinced of that.” Fuiman politely disagrees with the “backlighting” assessment by his colleague. However, both men believe other senses are in play in low-light or dark conditions. “If they’re catching fish in total darkness, then clearly they’re not using vision alone,” Fuiman noted. “It’s not likely that an animal is going to rely on one sense when it has so many available to it.” Hearing is out. The seals don’t vocalize while hunting under water, and the fish don’t make noise. Instead, the team believes the seals rely on vibrissae, or whiskers, which are not just hairs but very complicated sense organs with more than 500 nerve endings that attach to the animal’s snout. “We think they could detect the wake of swimming fish and use that to capture prey,” Davis said. Advances in technologyThe video will provide some of the key evidence for the hypothesis, according to Fuiman. The camera is positioned in such a way that the scientists can observe the seal’s muzzle and the whiskers, allowing them to see if there is any movement prior to a capture.

Photo Credit: Robyn Waserman/Antarctic Photo Library

A Weddell seal pops its head out of the water to take a breath.

“It will be interesting to see if their movement is more pronounced when it’s dark versus when it’s light,” Fuiman said. So far, the team has been busy building the three-dimensional dive profiles, and is now combining them with the video-recorded behavior. The fourth generation of the video-data recorder system currently in use is about one-fourth the size of the instrument deployed back in 1997, according to Davis. While the instrument has shrunk in size, its memory capacity has increased tremendously with digital technology. (The original video was on 8mm tape.) That means more data — and more work. “One of the curses of improving your technology is that we are deploying the animals for much longer periods of time, so now they’re out for many days,” Fuiman noted. Davis said he hopes to test a fifth generation this season, miniaturized to a degree that the whole package fits on the head of the animal. The system currently includes a backpack. Digital memory is no longer a limiting factor, at this point, Davis noted. “What defines the minimum size of the instrument now is the size of the batteries. It dictates how long you can record,” he said. The high-density lithium batteries are good for a one time use only at a cost of about $300 to $400. On the huntThe fieldwork itself may not be as difficult as surviving an Antarctic winter, but the temperature is still well below zero and unsettled weather quite common. But the real challenge is finding a suitable film star, Davis said. The subfreezing water is still warmer than the ambient temperature at that time of year, so it takes a little patience to locate a seal that has ventured out of a hole and onto the ice surface. Then it’s time for a little muscle, capturing and hauling the seal to a covered tent called a Jamesway where Williams’ team takes metabolic measurements. One experiment involves placing a box over the seal and measuring oxygen uptake by the animal. “If you understand how far you can push the mammalian heart or lung, you start to better understand the human condition,” said Williams, a professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at University of California-Santa Cruz (UCSC) Williams said previously in a press release from UCSC that she is also particularly interested in how the seals will respond to changes in their environment caused by global warming. “The seals are monitoring marked changes in the polar environment that will ultimately dictate their survival,” she said. The team then outfits the animal with the video-data recorder instruments before releasing it into a nearby hole. “It’s about a two-day operation,” Davis said. Each seal has a satellite transmitter and very high frequency (VHF) transmitter. When it eventually hauls out, it sends a signal to a satellite. Within about 90 minutes, the team receives the latitude and longitude location by e-mail, accurate to within 200 meters or so. Within a kilometer, the scientists can pick up the VHF signal and home in on their equipment. They can track about a half-a-dozen seals in a season. Some may not reappear for several weeks, though the recovery rate is 100 percent, Davis said. “It’s a waiting game.” And, based on the results so far, well worth the wait. NSF-funded research in this story: Randall Davis, Texas A&M University, Award No. 0739390 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |