|

Page 2/2 - Posted February 1, 2013

Scientists learning what it takes for seals to live in the wilds of AntarcticaIt’s unlikely fat and healthy adult Weddells are much bothered by such conditions, with some sporting the beer-belly equivalent of eight centimeters of blubber. But what about nursing mothers or half-starved juveniles still honing their foraging skills? Related Story

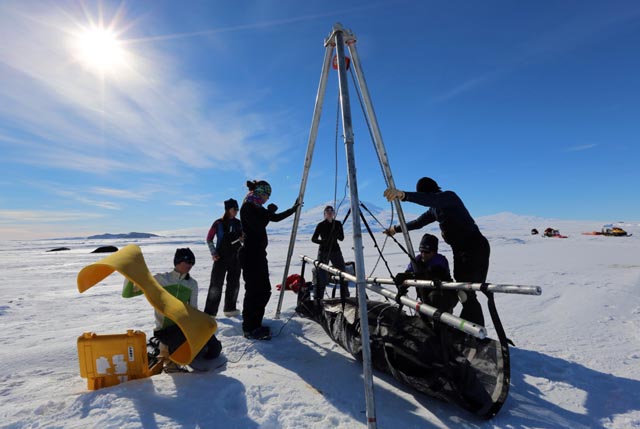

“Smaller, leaner animals are going to be at a disadvantage for heat loss,” Hindle explained. “They’re more likely to lose heat to the environment, and therefore they’re going to have to ramp up heat production.” The three-year grant from the National Science Foundation’s Division of Polar Programs Mellish noted that studying the range of physical types among the Weddell seals served two purposes. One was to look specifically at how animals of different sizes and shapes use energy to retain or release heat. In addition, the Weddell seals can serve as proxies, like a stuntman stand-in, for the more elusive pinnipeds in the Arctic. For example, small Weddell pups are about the size of ringed seals, while adults roughly match bearded seals in stature. “While it’s not exactly comparable, it’s the closest thing we’ve got, and it’s infinitely better than trying to model something based on random numbers,” Mellish said. “We have an enormous amount of variability [between individuals], which is really useful for us, because if you have the animals behave in the same way all the time, there’s no room for flexibility in the face of [climate] change.” Even with a colony containing hundreds of seals only a half-hour snowmobile away from McMurdo Station, it took the scientists weeks to find the right specimens for each physical type. “We did a lot of stalking and a lot searching,” Hindle said. Finding the right animal is just the beginning of about a half-day operation. The team first takes a surface heat profile of the animal using infrared imaging — a snapshot of its hot and cold surface areas. Then a tripod scale with a winch is used to weigh the seal; females can bulk up to about 600 kilograms. The scientists then set up a temporary shelter where team veterinarian Rachel Berngartt sedates the seal and monitors its health. Hindle and Mellish perform a medical physical, from doing an ultrasound to taking blood samples. Meanwhile, Horning and other team members epoxy their instruments to the fur of the animal. The heat flux sensors, data loggers, instruments and cables make the Weddells appear a bit like cyborg seals. The look is only temporary. The biologists will release each animal back to the wild for about a week, before they attempt to recover their data loggers and a blubber sample. After it molts, the seal will lose any sign that it has been involved in a scientific experiment. A long-range, satellite-linked transmitter on the animal first alerts the team back in McMurdo Station that it has hauled out onto the ice after a week has passed. The satellite ping comes within about two hours when a seal pops back out of the water. Each seal also carries a very high frequency tag, a short-range radio transmitter, which Hindle’s VHF antenna can locate. It still takes a bit of hunting around to locate the pup in the flat white afternoon on the sea ice this particular day. Eventually, the plump pup is found after a few more minutes of riding around the ice-locked islands where the seals tend to congregate. All four heat flux sensors — on the head, neck, under the flipper and across its flank — have come loose. “It will be interesting to see how many days of data we have on this guy,” Hindle said with a sigh. Later in the day, the team would locate a feisty female before returning to McMurdo Station. In the end, Mellish’s anxiety was unfounded: All of the seals were eventually found and the data loggers recovered with about a day to spare. It will still be another year before all the data are crunched and Hindle’s model completed. Then they may get a detailed answer on that seemingly simple question: Do seals get cold? “It’s really a ground-truthing program, because nobody really knows what it takes to be a seal in the wild in this sort of environment,” Mellish said. “You can guess, but nobody has directly measured it, so we’re pretty excited about that.” NSF-funded research in this story: Jo-Ann Mellish, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Award No. 1043779 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |