|

Bridge to the pastResearcher looks for evidence mammals traversed Antarctica to other continents 100 million years agoPosted November 6, 2008

Was part of Antarctica once a sort of highway upon which vertebrates, perhaps even early mammals, traversed between South America and Australia? Could some of these mammals have arisen in ancient Antarctica, before the continent turned into an inhospitable wasteland some 40 million years ago? Those are just some of the intriguing questions drawing Ross MacPhee “Antarctica was in between [Australia and South America], and presumably that was the highway, but we know nothing about when that highway was in operation or who was riding along it because there are no fossils,” MacPhee explained. Indeed, the only window into mammalian history in that part of Antarctica comes from Seymour Island right off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, according to MacPhee. Fossil evidence there is much younger, dating back to the late Middle Eocene, about 40 to 45 million years ago. “It’s pretty close, of course, to the overturn of the pre-existing climatic regime around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary, ushering in what we now regard as normal,” said MacPhee, referring to the time about 40 million years ago when the Drake Passage between South America and Antarctica widened far enough to allow a major ocean current through. Some scientists believe the event, the formation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, triggered the transition of Antarctica from a greenhouse to an icehouse. “It’s obviously important; if any further useful inferences are to be made about how mammals got [to Antarctica] and what they did there, we have to find other localities representing other slices of time,” MacPhee said. The timeframe MacPhee has targeted — 120 million years ago — is particularly intriguing, a time when therian mammals (placentals and marsupials) had only recently appeared on the geologic stage. Due to the dearth of vertebrate fossil evidence from Livingston, any find could prove to be significant. Mammalian fossils would not only connect Antarctica to other continents, but also possibly be a sign that certain groups of mammals arose on the continent. That’s one theory MacPhee is entertaining for a suborder of mammals called Xenarthra, which includes species like sloths and armadillos. “It’s not out of the question that xenarthrans arose in Antarctica,” he says. “It’s all extremely speculative and arm waving at this point, but my retort [is] since nobody has looked in a place like Livingston for early vertebrates of this sort, we just don’t know. It’s worth the effort to see if we can make any headway in this regard.”

Photo Credit: Ross MacPhee

Louis Jacobs examines 120-million-year-old frost-fractured sandstone on Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island.

The idea of land bridges connecting the continent is on far more solid ground. The Seymour finds, for instance, provide evidence of fauna that closely resemble those in South America. “What that tells is that there probably was, as has always been posited by both classic paleographers as well people doing plate tectonics, a persistent barrier, presumably at least partly subaerial, that connected Antarctic Peninsula with southernmost South America,” MacPhee said. This will be MacPhee’s second field season at Livingston in as many years, leading a small international team of researchers including Argentines and Australians. The plan is to base their camp at Byers Peninsula and look for deposits of bone and teeth. Poor weather all but ruined last year’s fieldwork. “We were killed by snow,” MacPhee said, noting that by all accounts the storms that plagued the team were the biggest in some years.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia Commons

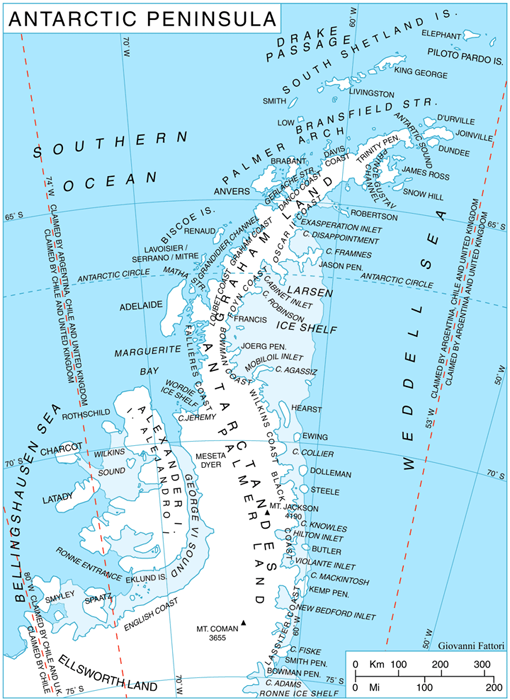

Antarctic Peninsula map shows Livingston Island, site of Ross MacPhee's project.

“What that meant was that all we were able to do was look at ridge tops because all the valleys were snow-filled,” he said, explaining it was impossible to dig through the snow cover to reach the sediments they needed for the project. “It would be like cleaning a million driveways to get down to anything resembling pay dirt.” That was particularly problematic for MacPhee’s team. They’re not looking for huge dinosaur bones (but would be happy to find them, of course) like those found on other Antarctic islands. Instead, the search will be for small bits of fossil evidence, particularly teeth of very small mammals on the size of modern-day rodents. That will require the use of screens to shift through sediment, MacPhee explained. “When you’re dealing with much smaller stuff you need to finely screen the sediments, and then examine the residue under a microscope to see whether or not you’ve turned up anything,” he said. Such fossils would probably be only 2 to 3 millimeters in size. Teeth are particularly attractive because they help the researchers identify which group of animals they found. Such finds would go a long way to helping the team unravel the dispersion of mammals long ago, an area of study called paleo-biogeography. “It’s really just a question of persistence and willingness to look,” MacPhee said. NSF-funded research in this story: Ross MacPhee, American Museum of Natural History, Award No. 0636639 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |