Shifting windsNew study says change in westerlies draws more CO2 out of the ocean and into the atmospherePosted March 20, 2009

Natural releases of carbon dioxide from the Southern Ocean due to shifting wind patterns could have amplified global warming at the end of the last ice age — and could be repeated as manmade warming proceeds, a new paper in the journal Science suggests. Many scientists think a change in Earth’s orbit triggered the end of the last ice age and caused the northern part of the planet to warm. This partial climate shift was accompanied by rising levels of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2), ice core records show, which could have intensified the warming around the globe. A team of scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory “The faster the ocean turns over, the more deep water rises to the surface to release CO2,” said lead author Robert Anderson In the last 40 years, the winds have shifted south much as they did 17,000 years ago, Anderson said. If they end up venting more CO2 into the air, manmade warming under way now could be intensified. Ice cores show that the ends of other ice ages also included increases in CO2. More Information

Two years ago, J.R. Toggweiler, a scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Anderson and his colleagues are the first to test that theory by studying sediments from the bottom of the Southern Ocean to measure the rate of overturning. The scientists say that changes in the westerlies may have been triggered by two competing events in the northern hemisphere about 17,000 years ago. The Earth’s orbit shifted, causing more sunlight to fall in the north, partially melting the ice sheets that then covered parts of the United States, Canada and Europe. Paradoxically, the melting may also have spurred sea-ice formation in the North Atlantic Ocean, creating a cooling effect there. Both events would have caused the westerly winds to shift south, toward the Southern Ocean. The winds simultaneously warmed Antarctica and stirred the waters around it. The resulting upwelling of CO2 would have caused the entire globe to heat. Anderson and his colleagues measured the rate of upwelling by analyzing sediment cores from the Southern Ocean. When deep water is vented, it brings not only CO2 to the surface but nutrients. Phytoplankton consume the extra nutrients and multiply.

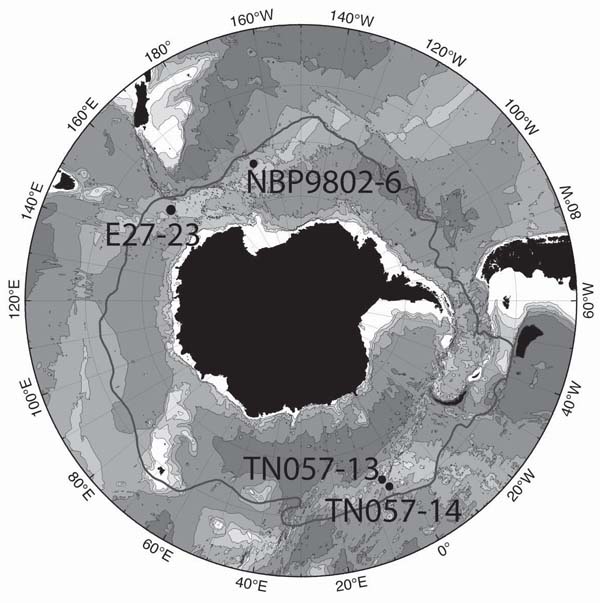

Graphic Credit: Robert Anderson/Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Map shows location of sediment cores used in the study.

In the cores, Anderson and his colleagues say spikes in plankton growth between roughly 17,000 years ago and 10,000 years ago indicate added upwelling. By comparing those spikes with ice core records, the scientists realized the added upwelling coincided with hotter temperatures in Antarctica as well as rising CO2 levels. At least one model supports the evidence. Richard Matear, a researcher at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Some other climate models disagree. In those used by the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change “It’s more complicated than this,” said Axel Timmermann, a climate modeler at the University of Hawaii. Even if the winds did shift south, Timmermann argued, upwelling in the Southern Ocean would not have raised CO2 levels in the air. Instead, he said, the intensification of the westerlies would have increased upwelling and plant growth in the Southeastern Pacific, and this would have absorbed enough atmospheric CO2 to compensate for the added upwelling in the Southern Ocean. “Differences among model results illustrate a critical need for further research,” Anderson said. Future research, he added, should include “measurements that document the ongoing physical and biogeochemical changes in the Southern Ocean, and improvements in the models used to simulate these processes and project their impact on atmospheric CO2 levels over the next century.” Anderson said that if his theory is correct, the impact of upwelling “will be dwarfed by the accelerating rate at which humans are burning fossil fuels.” But, he said, “It could well be large enough to offset some of the mitigation strategies that are being proposed to counteract rising CO2, so it should not be neglected.” The National Science Foundation |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |