Killer newsScientists suggest several new species of orcas, including in the AntarcticPosted May 14, 2010

New technology in gene sequencing confirmed what scientists have long suspected about Orcinus orca: The large marine mammal commonly referred to as a killer whale actually represents several genetically distinct species, including at least two new ones that swim in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. Scientists analyzed tissue samples from more than 100 killer whales from the North Pacific, the North Atlantic and the Southern Ocean. As a result of the study, published last month in the journal Genome Research, the scientists suggest there are two types of killer whales in the Antarctic and a mammal-eating “transient” killer whale in the North Pacific, in addition to the “standard” black-and-white orca of SeaWorld fame.

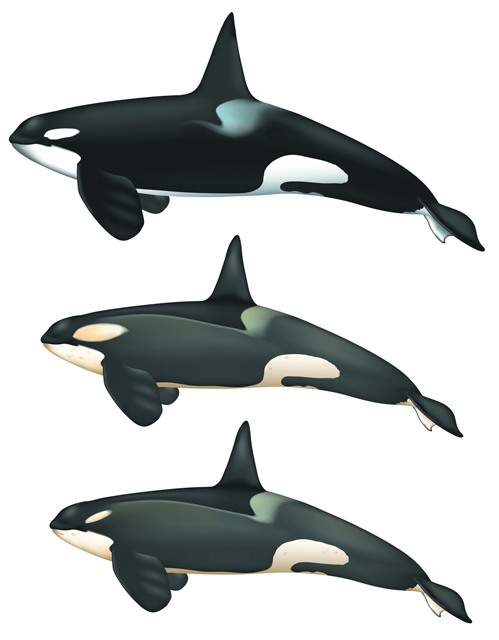

Graphic Credit: Uko Gorter

A graphic shows the "standard" killer whale at top, followed by type B and type C.

Part of the study is based on Antarctic fieldwork conducted by Robert Pitman, with NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center Pitman said he was aware of previous scientific literature by Soviet-era scientists in 1979 and 1980 that there were killer whales in the Antarctic that appeared dissimilar enough to be different species. He first traveled down to McMurdo Station with help from the National Science Foundation During the trip, he spotted three distinct types of killer whales, and collected tissue samples from all three. Pitman made two subsequent trips to McMurdo and several expeditions to the Antarctic Peninsula for additional observations and sampling. “After we published papers about our observations, and I collected a series of tissue samples, I was able to interest a number of my co-authors [on the Genome Research paper] into looking into species-level differences among killer whales worldwide, including the very distinctive Antarctic forms,” he wrote via e-mail while in the field tagging killer whales off the coast of California. The two additional types of killer whales in the Antarctic are not only genetically different. One (Type C) dines on fish while the second (Type B) prefers a diet of seals. “Dietary specialization seems to spur speciation in killer whales, even among populations with overlapping distributions, because of the behavioral and ecological divergences involved with taking different kinds of prey,” Pitman explained. For example, fish-eating orcas use echolocation almost continuously to communicate among group members and to locate their prey while those that prey on mammals rely on silence and stealth because their prey has acute hearing abilities. “Our information on dietary specialization in Antarctica comes mainly from observations, but elsewhere, in the North Pacific for example, these differences in diet are reflected in chemical signals in the skin and blubber of the different ecotypes,” he said. Differences in behavior, feeding preferences and physical features among killer whales around the world made it likely there were several species. However, DNA analysis had been inconclusive because of scientists’ inability to map the entire genetic picture, or genome, of the whales’ mitochondria, an organelle within the cell inherited from the mother. “The genetic makeup of mitochondria in killer whales, like other cetaceans, changes very little over time, which makes it difficult to detect any differentiation in recently evolved species without looking at the entire genome,” said Phillip Morin Previous coverage

The researchers used a relatively new method called highly parallel sequencing to map the entire genome of the cell’s mitochondria from the worldwide sample of killer whales. Highly parallel sequencing of DNA is far faster and less costly than historical methods of analysis, according to NOAA. For instance, the examination of mitochondrial DNA genome in one sample can take several months. The new technique allows researchers to analyze 50 or more samples in just a few weeks. While the paper suggests three new species, the authors say more species may emerge upon further analysis. Pitman said there may be at least a half dozen new species, including a fourth killer whale (Type D) in the Southern Ocean that he believes will prove to be a different species. The authors of the study also say that determining how many species of killer whales there are is “critically important for resource managers to establish conservation priorities and to better understand the ecological role of this large and widespread predator in the world’s oceans.” For instance, Pitman noted that Type C killer whales that feed on fish in the Ross Sea may be under stress from commercial toothfish longlining operations. “This need for data to make management decisions should make it likely that someone should be looking at how the fishery may be impacting this species,” he said. The NOAA biologist also said that the killer whale study highlights how far science still has to go in understanding the vast array of life on the planet and its oceans. “The killer whale is arguably the most universally recognizable animal that swims in the ocean,” he said. “It has been studied intensively for decades, and we still don’t even know how many species there are out there. I think it is a clear indication about how little we know about what swims in our oceans.” NSF-funded research in this story: Robert Pitman, Richard LeDuc and Wayne Perryman, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Award No. 0338428

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |