Hitting the groundInternational project monitors permafrost in AntarcticaPosted September 23, 2011

The thawing of frozen soil in the Arctic is becoming a familiar story. Concerns range from the release of powerful greenhouse gases into the atmosphere to the destruction of infrastructure like roads and buildings as the ground collapses from the melting of ice-rich permafrost below. The picture in the Antarctic is less clear, largely due to the scarcity of monitoring sites until recently. An international effort is now under way to learn more about the characteristics of Antarctic permafrost and its sensitivity to climate change. The program is called PERMANTAR “We chose Palmer [Station] Climate records from a Ukrainian research base, Vernadsky Station Bockheim has a four-year project from the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs “In the Arctic, there’s a lot of carbon locked up in the upper part of the permafrost,” he explained. “The concern in the Arctic is that as you warm those soils and increase the thickness of the active-layer — in other words, the depth to the permafrost table — the carbon can be available for oxidation chemically and by microorganisms and go back into the atmosphere as CO2, and that exacerbates the warming.” Carbon dioxide is a key greenhouse gas that helps trap heat in the lower atmosphere, warming the planet. It is rapidly approaching 400 parts per million — higher than any time in the last 800,000 years, based on ice core records. However, Bockheim said researchers believe climate change in the Antarctic may be a double-edge sword when it comes to the carbon cycle. “In the Antarctic, with the warming of the climate there, we’re going to see, and we are already seeing in certain places, an increase in the vegetation, an increase in biomass, and an increase in soil organic matter. So, the Antarctic might become a receptacle for the carbon, which is in contrast to the Arctic,” he said. But it is unclear how effective new vegetation may be in sequestering carbon dioxide. A paper published two years ago in the journal Nature suggested that additional tundra plant growth from climate change in the Arctic may initially keep up with rising carbon dioxide. But if thawing continues, the permafrost will spew carbon for decades, and the plants will become overwhelmed. Less than .5 percent of Antarctica isn’t covered by ice. However, Bockheim and his colleagues predict that while the soils of the Antarctic Peninsula and offshore islands comprise only 20 percent of the ice-free area of Antarctica, they will account for more than 80 percent of the soil organic carbon. Hence the need to monitor the soils around the peninsula region.

Click on the image above to see a YouTube video interview with James Bockheim on his research involving permafrost. The link will take you away from this page to a nongovernment website.

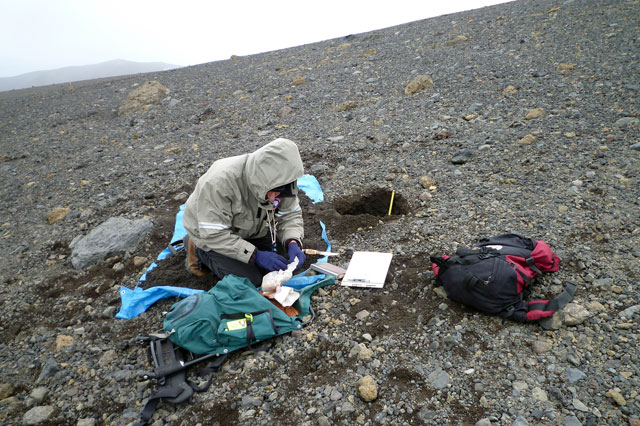

Bockheim, who has previously worked on the far colder, drier soils of the McMurdo Dry Valleys He and two students then worked out of Palmer Station for nearly a month over March and April to install shallow soil monitoring stations that consist of strings of sensors that measure soil temperature at regular intervals. The data from the thermistors will give the researchers an idea about the thickness of the active-layer depth — the portion of the ground that regularly thaws and freezes during the year. This year the small team from Madison will be joined by two colleagues from Portugal to install deeper boreholes that will monitor temperatures in the permafrost as far down as 15 meters at sites around Palmer Station and at an Argentine station about 100 kilometers north. All the data from PERMANTAR will feed into a computer model that can predict the possible carbon flux and other impacts from climate change based on the temperature, chemistry, depth and distribution of permafrost. Surprisingly, the soils of the Antarctic Peninsula offshore islands are somewhat similar to those in the Arctic, according to Bockheim. In fact, the Palmer area receives almost as much rainfall as Madison, he noted. “To me, it’s like working in Alaska in August or September when it’s spitting rain and snow,” he said. NSF-funded research in this story: James Bockheim, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Award No. 0943799 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |