|

South Pole Station Archives - 2010 NASA makes rare flight over South Pole StationPosted October 29, 2010

An early November storm at the South Pole Station The IceCube Neutrino Observatory Only seven holes remain to be drilled, though the observatory is already functional, collecting data on the rare collisions of neutrinos, elusive subatomic particles, with the atomic nuclei of the water frozen into ice.

Photo Credit: Sarah DeWitt/NASA

View out of the cockpit of NASA's DC-8 aircraft of the South Pole Station.

The multinational science team, led by Francis Halzen Another big-ticket item at the South Pole this season is work to repair the azimuth on the South Pole Telescope Installation is also underway for the Small Polarimeter Upgrade for Dasi (SPUD) telescope, a next-generation instrument that is attempting to learn more about the process that occurred following the Big Bang In recent years, visitors to the South Pole have also increased exponentially — at least relatively speaking. One of the more unique groups to make the trip to 90 degrees South in November was a scientific expedition from India. The eight-member team reached the South Pole on Nov. 22 after traversing about 1,500 miles in nine days from Maitri, India’s second permanent research station. The expedition traveled on four specialized arctic truck vehicles, which had some problems due to the intense cold temperatures. “We had a little problem with radiators and axles of the vehicles, which we replaced on the way,” said Rasik Ravindran, the expedition leader, in online news reports. Another type of visitor made just a quick pass at the South Pole — literally. A NASA The NASA plane completed 10 flights over 115 hours, covering 40,000 nautical miles – nearly enough to fly around the Earth twice. The National Science Foundation, while not directly involved in IceBridge, handled the mission’s environmental permits for working over Antarctica. In addition, staff at South Pole provided high-rate GPS data to the IceBridge mission, which were critical for the long South Pole mission that originated from Punta Arenas, Chile. First flights arrive at South Pole Station for summerPosted October 29, 2010

The lonely winter is over at the South Pole Station The first flights of the summer season arrived in October. Two Basler BT-67 aircraft landed at the U.S. Antarctic Program’s

Photo Credit: Ella Derbyshire/Antarctic Photo Library

A Basler aircraft lands at the South Pole in 2009.

The planes were en route from the British Antarctic Survey’s Rothera Station One Basler, a retrofitted Douglas DC3, returned to Pole on Oct. 19 (local time) with new personnel from McMurdo, officially marking the beginning of the summer field season. Temperatures that day ranged between minus 68 and 58 degrees Fahrenheit. The Baslers, along with Borek Air’s de Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otters, provide deep-field support to science parties in Antarctica. In addition, the New York Air National Guard The summer population will shoot up to more than 200 personnel and scientists over the next several months for another typically busy, but short field season. The construction crew for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory The South Pole Telescope Looking for the closest exit as winter comes to an endPosted September 17, 2010

Two of the best days during a South Pole winter might just be when the last summer flight leaves — and, ironically, the day you leave. The former is a distant memory for the 2010 South Pole Station

Photo Credit: Nicholas Morgan

A USAP participant enjoys the view of twilight, signaling the return of the summer at the South Pole.

Sept. 6 also marked the beginning of civil twilight, the final stage of sunrise before the sun breaks the horizon. Civil twilight means the window coverings that keep artificial lighting in the main station building from disrupting experiments focused on the night sky can be taken down. The latter of the two best days of winter is now in the forefront of everyone’s mind. Scheduled redeployment dates are being made, and post-Ice travel plans are well under way. Fittingly, one of the best-attended social events of the second half of winter was a play directed by winter-over carpenter David Holmes — Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit. The performance starred Holmes as the Valet, UT apprentice Shelby Handlin as Estelle Rigault, physician assistant Emily Wilson as Inez Serrano, and greenhouse technician Joe Romagnano as Joseph Garcin. The play is about three deceased people, each of whom finds the other two individuals unbearable, who must spend the rest of eternity locked in a room together — Sartre’s metaphor for spending eternity in Hell. According to preventative maintenance foreman James Travis III, “It was like Cats performed in Hell, only without the cats.” Holmes chose to direct this particular play at the South Pole because when the last plane of summer leaves in mid-February — and we handful of winter-overs are left on our own with one another for the next eight months — it can seem like we have no exit. However, unlike the three souls in Sartre’s play, we do have an exit, and it is finally near. The sun is almost up and there is a blue tinge is in the sky. Sun-drenched beaches are beckoning! South Pole observatory readies for ozone hole formationPosted August 13, 2010

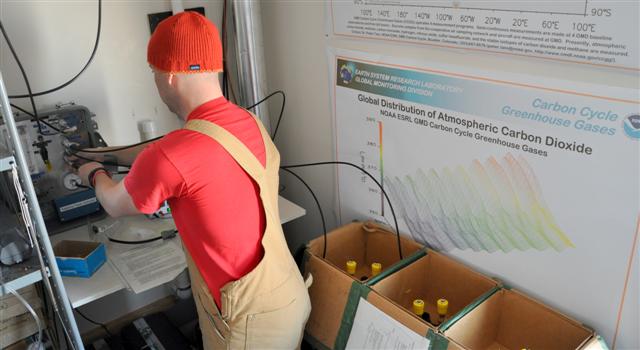

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Every year in mid- to late August, the polar vortex, an isolated area of extremely cold air in the stratosphere, develops over the South Pole, causing the formation of stratospheric clouds. These clouds create the ideal base for manmade chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the atmosphere to break down ozone. CFCs are chemical compounds that used to be common in products like aerosol sprays. An international treaty called the Montreal Protocol began limiting human use of CFCs in 1987, and completely phased them out by 1996. However, CFCs have an atmospheric life span of more than 50 years, so there are still millions of CFC particles floating around Earth’s atmosphere that were emitted as long ago as 1960.

Photo Credit: Nick Morgan/Antarctic Photo Library

NOAA Corps officer Nick Morgan fills flasks with air from the South Pole in the Atmospheric Research Observatory. The facility also monitors ozone depletion as part of its atmospheric observations.

Every August, when the polar vortex forms, the conditions are perfect for CFCs to eat away enough ozone to form a hole in the ozone layer. The polar vortex only exists for a short period of time, and disappears once the temperatures begin warming back up in October. But the residual effect of the CFC damage to the ozone during that time causes the hole to remain until late November or December. During this entire time period, NOAA is busy at work at the Atmospheric Research Observatory One method is to launch ozone balloons. These balloons are specially equipped with devices to measure ozone levels in the stratosphere, and are launched two or three times per week to begin their journey 20 to 30 kilometers straight up. The second method is to use a Dobson spectrophotometer, named after the British meteorologist who developed it. This is a device that can measure ozone levels in vertical columns within the stratosphere from the ground In a healthy atmosphere, levels of ozone sharply increase at the lower altitudes of the stratosphere, and sharply decrease back to normal levels at the middle to upper altitudes. NOAA’s studies have shown that when the polar vortex exists, ozone levels begin their same pattern of increasing at the lower altitudes of the stratosphere, but immediately drop to zero where stratospheric clouds have developed, forming the ozone. That allows the sun’s dangerous, cancer-causing, high-frequency ultraviolet rays — about 97 percent of which are absorbed by the ozone layer when it is in tact — an unobstructed path to the Earth’s surface. According to winter-over NOAA Corps representative Nick Morgan You can follow Morgan's work and adventures at the South Pole at his blog Monitoring Earth's Atmosphere on The Exploratorium's Ice Stories Web site. A French-U.S. team will arrive at McMurdo Station ***

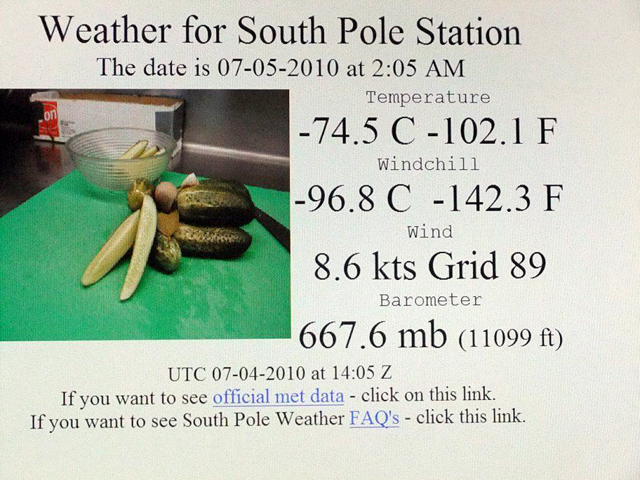

In news from the troposphere, the layer of atmosphere below the stratosphere where people live and breathe, the South Pole experienced some extreme weather. The Fourth of July weekend broke two record low temperatures. On July 3, the minimum temperature of -74.3°C/-101.7°F broke the previous record of -72.8°C/-99.0°F set in 1967. The next day, on July 4, the minimum temperature of -75.0°C/-103.0°F broke the previous record of -71.9°C/-97.4°F set in 1972. July was also an extremely windy month, and between July 15 and 22, several peak and average wind speed records were broken or tied. The windiest day occurred on July 16, with a peak wind speed of 42 knots/48 miles per hour, which broke the previous peak wind speed record of 32 knots/37 mph set in 1978. All that weather made for a cloudy month as well, tying the record for most cloudy days in July at the South Pole at 16, set back in 1990. Midwinter brings deep freeze to South PolePosted July 16, 2010

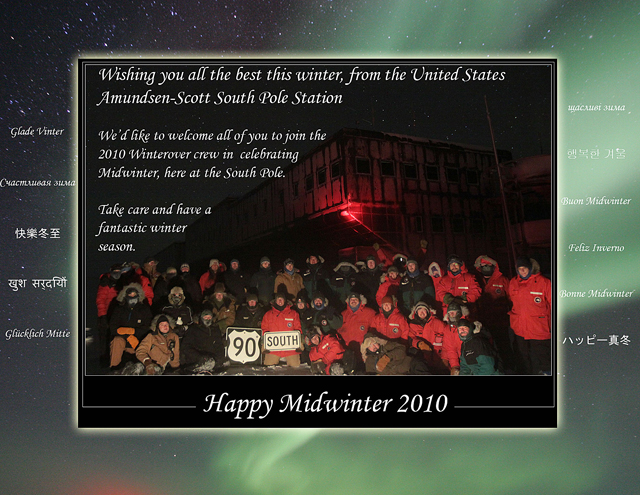

June 21 marked Midwinter Day for everyone currently on the world’s southernmost continent. Those of us at the South Pole Station Midwinter Day, or the winter solstice for the entire southern hemisphere, is the moment in time when the sun is at its lowest point below the horizon. On June 22, it begins making its journey back toward our skies. Given that the South Pole has only one sunset and one sunrise per year — and that it is generally dark for the entire winter around the rest of Antarctica — Midwinter Day is a unique holiday for this continent. The Midwinter festivities began with a formal dinner. Most Polies donned their nicest attire that they brought with them. The meal was highlighted by the main course of filet of beef seared in duck fat, with black truffles and foie gras, and handmade lobster and pumpkin ravioli. The traditional South Pole party followed the midwinter toast and five-course feast into the wee hours of the morning. Just two weeks later, it was time for yet another celebration — July 4th. Since the South Pole Station is an American base inhabited mostly by U.S. citizens, America’s Independence Day is yet another reason we have to gorge ourselves on good food and throw a party. In following with yet another South Pole tradition, an entire pig had been set aside prior to the end of the summer season for a Fourth of July barbeque. There was plenty of hog to go around, as well as burgers, hot dogs, and other traditional American fare. Real fireworks aren’t allowed, but we played a video of a professional firework display for everyone to “ooh” and “ahh” over. The July 4th weekend also brought about the longest duration of extremely cold weather we have seen this year. The temperature dropped below minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit for a considerable length of time, and set record lows from July 2 to 5. This gave everyone interested plenty of time to complete a third South Pole tradition — joining the 300 Club — if they had not done so back in April when the temperature first dropped below the magical number. Now, as we move past midwinter and perhaps start to see a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel, people’s thoughts begin to turn to planning vacations and figuring out life post-South Pole. At first it may seem like there is still a long way to go, but as anyone who has wintered here before can attest, these last few months fly by. Before we know it, sunshine will be beating down on us and we will be preparing for the planes to arrive for another summer season. Big science at Pole searches for dark matter, neutrinosPosted June 18, 2010

Compiled from the May 2010 South Pole Station Science Report by Dana Hrubes, station science leader. May is the month at South Pole Station

Photo Credit: Dana Hrubes

A view of the Milky Way Galaxy, with the South Pole Telescope in the forefront.

Station operations ran smoothly throughout the month. All the emergency response teams conducted training, and a drill was conducted on April 27. Dana Hrubes, a winter-over on the South Pole Telescope South Pole science projects collected valuable data throughout the month, with the big three — South Pole Telescope (SPT), IceCube Neutrino Observatory The SPT is surveying the night sky for galaxy clusters, which will eventually help scientists understand the nature of dark energy, a force believed to be responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe and about 75 percent of its energy-mass. In May, the telescope continued on a new scan of the cosmic microwave background (CMB). The SPT can locate galaxy clusters by detecting distortions in the CMB, called the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (SZ) effect. In 2008, the telescope detected its first galaxy clusters using the SZ effect. IceCube is a cubic-kilometer-sized detector buried under the ice at the South Pole. Its focus is the neutrino, a subatomic particle that could offer important clues to major galactic events such as supernovae. This winter, IceCube started collecting data on the 20 new strings of detectors that were installed during the summer, bringing the observatory up to 79 strings and a total of 4,956 digital optical modules. Construction of the last seven strings will finish in 2010-11. BICEP II is a microwave telescope that is also looking at the CMB, the time about 400,000 years after the Big Bang when the universe cooled enough for ordinary matter to form. It hopes to detect a “signature” in the CMB of the time just after the Big Bang when the universe expanded exponentially, to learn more about that inflationary period. As alluded to earlier, May was a stormy month. Five days experienced record peak winds, topping out at 48 miles per hour on May 28, which was also a new record for the month of May. There were only two clear days of the month, which broke the previous record of three days for the least number of clear days in May set in 2006. Consequently, the 13 cloudy days broke the record for the greatest number of cloudy days in May (12) set in 1999. Now serving fresh garden salad at the South PolePosted May 7, 2010

While the brutally cold temperatures and stunning auroras may be the biggest points of public interest during a South Pole winter, it’s often the little things about life at the bottom of the world that are most interesting. Like eating vegetables.

Photo Credit: Jeff King

Greenhouse technician Joe Romagnano works in the growth chamber, an oasis of green and humidity at the South Pole.

After all, garden fresh vegetables do not stay fresh for nine months — the elapsed time between the last plane of the previous summer and the first of the next. We receive no cargo for the duration of the winter. And a two-mile-deep pile of snow and ice on which South Pole Station So, how exactly do the temporary residents at 90 South heed the childhood teachings of their parents to finish their veggies before they have dessert? For one, canned vegetables are simple to store and last virtually forever. Plus, the station’s staff of professional cooks knows enough different ways to prepare green beans that, even after nine months, they manage to continue conjuring up unique veggie dishes. What most people do not know, though, is that we are also able to have fresh vegetables. Yes, it’s true. We had fresh garden salad with our dinner last night. The provider of such luxuries is our Hydroponic Growth Chamber — a greenhouse — that resides in a quiet, albeit most lively, little corner of the Elevated Station. Over the course of the five years that the Growth Chamber has been cranking out freshies, many improvements have been made in the quality and variety of veggies produced. In the beginning, most harvests produced an abundance of lettuce and cucumbers but not much else. According to 2010 winter-over greenhouse technician Joe Romagnano, the Growth Chamber is currently producing between 35 and 40 species of plants, only seven of which are lettuce. The station’s 47 winter-over have already feasted on more than 500 pounds of freshies over the last 12 weeks. Herbs, such as sage and cilantro, are being gown this year, and after cracking the secret to harvesting the first successful spinach crop in South Pole history in 2009, Joe has passed the torch of growing spinach to Winter Site Manager Mel MacMahon through his Adopt-A-Crop program. This fun learning experience allows community members to grow a crop “from seed to feed” under Joe’s tutelage. There are currently seven Polies participating, growing such vegetables as radishes, habanera peppers and eggplant. The Growth Chamber also quietly leads a double life. Antarctica is the driest place on earth, and penguins and seals do not venture anywhere near the South Pole. The Growth Chamber provides Polies with their only escape from the skin-cracking dry air of Antarctica, and their only exposure to non-human life. Entering the greenhouse can cause complete sensory overload for someone who has been at Pole for a few months. In fact, its impact on the human psyche in an environment completely lacking sensory stimuli is so great that human interaction with the Growth Chamber can provide NASA and universities with data they can use in researching advanced life support systems for potential long-duration space flights, such as colonizing the moon or going to Mars. That all sounds pretty glamorous and important; but Polies tend to be a humble group of people. Some hard work goes into keeping the Growth Chamber operational. In the same breathe as talking about the human psyche and space exploration, if you ask Joe Romagnano what he does all day, he says, “I spend about 75% of my time cleaning stuff.” Sun sets at South Pole: Bring on the aurorasPosted April 16, 2010

March 23 was just another day at South Pole Station But there was one difference. It was the last time we would see the sun for six months. Quite a mind-boggling phenomenon, if you really stop to think about it. Unless you have spent a winter at the geographic North Pole — or six months living in a cave — you have to be one of about 1,300 people in the history of humankind who have spent a winter at the bottom of the planet to enjoy this unique experience. The new faces and old hands, alike, anxiously await the last lingering rays of sunlight from below the horizon to give way to the deafening black sky, lit up by seemingly millions of stars and, of course, those ever sought-after Aurora Australis. On the surface, the station may seem much smaller during the winter. The outer buildings are shut down. All the windows on the elevated station are boarded up to prevent artificial light from escaping and interfering with science experiments that require darkness and only natural, ambient light. Despite these physical aspects of a closed-off, isolated building in the middle of nowhere, the six months of dark provide one opportunity so large that it renders the smallness irrelevant — the privilege of gaining a perspective of the world that only a few have ever, and will ever, get to see.

Photo Credit: Patrick Cullis/Antarctic Photo Library

An aurora above South Pole Station in June 2009.

Anyone who knows a winter-over Polie has heard the stories and descriptions, seen the pictures, and probably wonders themselves, “What is it like to stand outside at minus 90 degree Fahrenheit — with not a cloud in the sky or a breathe of wind — and look up to see stars seemingly at the end of the universe and the green, purple and red auroras dancing the tango for hours across the sky?” Imagine going to a laser light show at the planetarium. The room has a chill in the air. The lights start, choreographed to music by Pink Floyd, which really creates that “wow” feeling of being in another world. Now imagine the universe, rather than a person, created the lights, then turn the thermostat down by 150 degrees, exchange Pink Floyd for dead silence, and multiply the “wow” feeling by a thousand. This is one of the major reasons Polies become Polies in the first place. And now it is that time of year. Our eyes are on the sky, and our camera batteries are charged and ready. Someone cue up Dark Side of the Moon! South Pole crew braces for winter seasonPosted March 12, 2010

When the summer crew turns the reins over to the winter-overs, the South Pole Station This year the last flight of the summer field season, which departed South Pole at 3 a.m. on Valentine’s Day, left behind 47 people to keep the station running until October. “Skier 301 is on deck. The crossing beacon is on. Please avoid the skiway. This is the final outbound passenger flight of the season,” sounded over the all-call and radios. A handful of winter-overs, who had either stayed up or set their alarm, stumbled out to the flight deck to wave goodbye to summer, as the remaining summer-only folks boarded the plane for McMurdo Station The ski-equipped LC-130 offloaded the last bit of fuel for winter, lifted off, made a hard bank to the right, and circled around for a low-level flyover, providing excellent photo opportunities. A few people still on the ground waved. Some clicked their cameras. Some toasted the beginning of winter. And, as always, a few jokingly cried out for the plane to come back and get them, as we watched it disappear over the horizon. The walk back into the station was quiet and serene. The sound of propellers loudly buzzing on the flight deck — gone. The sound of night-shift equipment operators driving bulldozers — gone. The sound of large groups of people socializing in lounges — gone. Walking into the station: the clank of the external freezer door closing and the lumbering of bunny boots on the floor echoed through the hallway. Otherwise, silence. Those who have done this before smiled with the knowledge of what’s to come, and those who have not are excited for their new adventure.

Photo Credit: Michelle Handlin/Antarctic Photo Library

James Reaves, South Pole safety engineer, is one of 47 Polie winter-overs.

The next day was Sunday, so many of us ushered in the new season by upholding a long-time South Pole tradition — setting up a movie theater in the gym and watching The Thing the day after the last flight until summer begins again in October. Monday, it was back to work. We have many tasks to accomplish to winterize the station. To name a few: The fuel lines must be taken down and stored, outlying buildings from the main station must be prepared for electricity and water to be shut off, and the flags that line the skiway and approach markers must be taken down to prevent snow drifting. With 21 of the 47 people having previously wintered at Pole before — for a cumulative 839 months of time in Antarctica — this was nothing new, and winterization went without a hitch. Now we look forward to the sun giving way to the winter darkness. Much to celebrate at South Pole as new decade beginsPosted February 5, 2010

South Pole Station Polies transformed the gym — normally used for volleyball, basketball, swing dance class and morning stretching — into a New Year’s Eve party hall, with decorations, lighting, and a large stage. The evening’s entertainment showcased the talent and many hours of practice put in by the station’s resident bands and musicians. Blue grass, folk, country, rock-and-roll, and even a punk-rock cover band, performed. During intermission, a Wearable Art fashion show featured some of the spare treasures lying around the South Pole. Polies scavenged for spare pieces of rope, coaxial cables and cardboard boxes to make wearable creations to show off down the model runway. The crowd favorite was a giant cardboard box made into a wearable forklift, with operating lifting tongs, worn by a seasoned machine operator. The beginning of 2010 wasn’t the only thing to celebrate at the South Pole this month. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory finished drilling all 20 holes into the ice sheet this season on Jan. 20 — a full 10 days earlier than originally projected. The experiment requires a team to drill 2.5 kilometers into the ice to deploy a string of digital optical modules to learn more about neutrinos, subatomic particles from space. [See recent story: Big science.] The drill crew stuck around to empty their water lines, winterize the construction camp and prepare for next summer, which will be their final drilling season. The dome deconstruction also finished this month. The construction crew dismantled all of the panels, and the station carpenters have been busy crating the pieces for the cargo department to ship them off the continent. The annual South Pole Film Festival (SPIFF) debuted on Jan. 23 to a packed room. The film festival premieres short films written, filmed and produced at the South Pole. A rap music video parody of “I’m on a Boat” titled “I’m at the Pole” garnered many cheers and a repeat showing. Several season-long competitions ended last month, including Scrabble and cribbage tournaments. Winners received prizes for local restaurants in Christchurch, New Zealand. Some of the coldest competition occurred during the annual South Pole Snow Sculpture contest. Large blocks of snow were placed near the ceremonial pole for use. Teams and individuals willing to bear the cold sculpted the ice into frozen art. Winners included a pair of polar bears (ironic, since they only live in the Arctic) and a sculpture in tribute to the station’s beloved, if belligerent, Frosty Boy ice cream machine. Yes, that’s right: The South Pole said goodbye to a very dear and beloved friend this month. Frosty Boy, a soft-serve ice-cream machine, finally swirled cold, sugary goodness into its last cone. Though Frosty Boy has been replaced in the dinning room by a scoopable ice-cream freezer unit, it will never be replaced in our hearts. May you rest in peace, Frosty Boy. Cargo, fuel arrive at South Pole in unusual waysPosted January 8, 2010

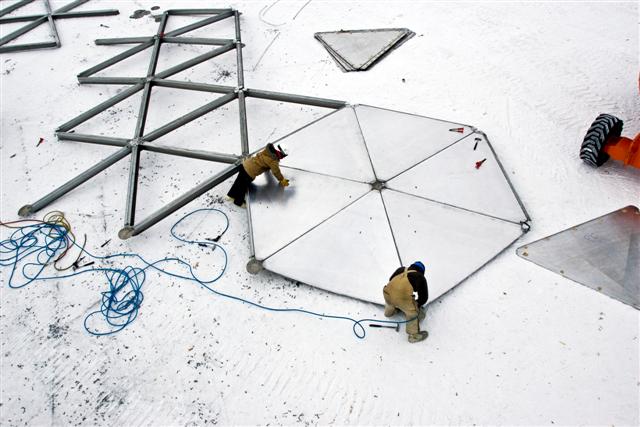

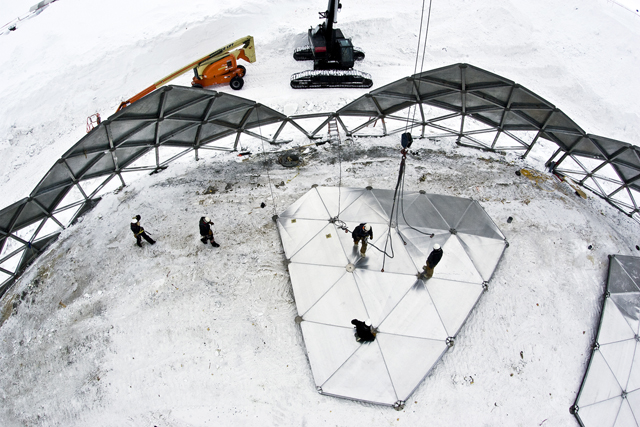

The South Pole Traverse, a caravan of tractors and heavy machinery charged with crossing about 1,000 miles of Antarctic ice, arrived at South Pole Station The is an important part of station operations, as fuel generally arrives on LC-130 flights operated by the New York Air National Guard The traverse’s arrival has kept the South Pole fuel crew busy offloading the massive delivery. The fuel bladders actually pose an interesting dilemma for the crew: The LC-130s have pumps to push fuel off the plane into the station’s holding tanks. But the traverse bladders need to have the fuel withdrawn, similar to sucking on the straw of a juice box. In order to accommodate both of these needs at the South Pole, the “fuelies” use a unique valve, created especially for the South Pole Station’s fuel pumping needs, which can regulate both positive pressure and create negative pressure. Besides being stocked with fuel, the South Pole was also stocked with dried food goods in December via an Air Force C-17 airdrop. The plane made two circles along the drop zone, dropping 13 bundles weighing approximately 14,000 pounds. The bundles consisted of dry food such as flour, dried milk, rice and cereal. Airdrops during the summer are done primarily as practice in the event of a need for a winter resupply mission. Many of the station crewmembers hiked out to watch the bundles drop and take pictures of the C-17 flying overhead from a designated safety zone. The South Pole growth chamber, the station’s specially designed hydroponic garden, is gearing up for the winter-over season. The technicians have been busy cleaning in preparation for the upcoming winter growing season. South Pole community members chipped in and volunteered their time during a Christmas Eve planting party by planting various fruit and vegetable seeds in the hydroponic growth chamber. These seeds will grow into plants that will be harvested by the winter staff long into the winter when planes have stopped delivering fresh produce to the station. The growth chamber team isn’t the only crew working hard to finish projects before the season ends. The carpentry crew has been racing to finish installing the last of the elevated station’s paneled siding. The final areas they’re attacking are the underbelly of the station, its support pilings and several smaller stand-alone buildings. The deconstruction of the old station dome is moving at a rapid pace. A crew of six started dismantling the dome’s 164-foot circumference base while waiting for special tools to begin taking apart the top of the dome. The crew ended December working from the top of the structure, removing triangular plates in expanding rings. [See related story: Deconstruction of the Dome.] The IceCube Neutrino Detector Observatory project The South Pole celebrated Christmas with a special meal in the dining hall and the annual Race Around the World. This year the 2.25-mile course consisted of loops around both the old dome and the Elevated South Pole Station. Curtis Moore won men’s first place with a time of 17:17:43 and Emily Thiem won women’s first place with a time of 20:48:33. Highlights included a welder who ran backwards, several festive costumes, and tractors decorated as medieval floats. |

Home /

Around the Continent /

South Pole Station Archives - 2010

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |