Byrd Camp resurfacesNSF to resurrect deep-field site to support major West Antarctica sciencePosted June 12, 2009

The International Polar Year (IPY) A key element in the West Antarctica Support (WAS) project plan is the revival of one of the U.S. Antarctic Program’s Originally established during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) More on Byrd

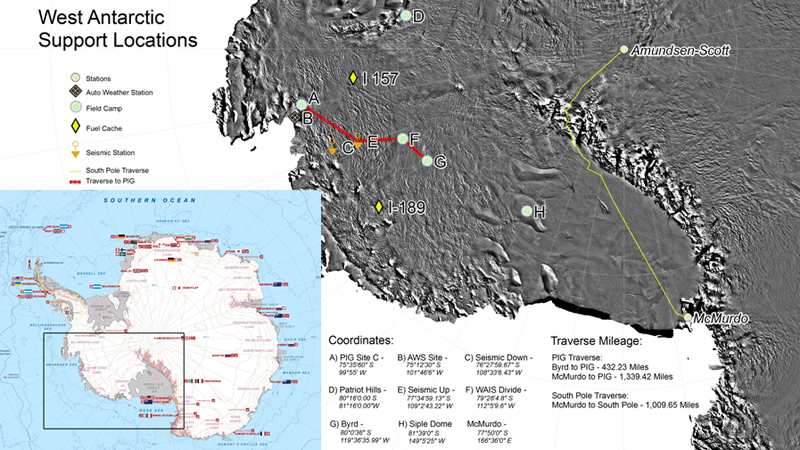

Now, a completely new camp capable of supporting upwards of 50 people will be constructed this coming field season, as scientists fan out across West Antarctica to install a GPS and seismic network, to fly radar-equipped airplanes over the ice sheet and to peer underneath the continent’s fastest-moving glacier at Pine Island. “We’re starting new. A new skiway. Everything,” said Chad Naughton, a Science Planning manager for Raytheon Polar Services Co. (RPSC) Naughton’s job has been to help plan the camp for its many tasks ahead, including its service as a waypoint for a second field camp at Pine Island Glacier (PIG), which is even farther from the U.S. Antarctic Program’s logistics hub at McMurdo Station “Byrd is actually the beachhead to Pine Island. Byrd will become the staging point for the Pine Island traverse,” said Naughton, referring to an operation planned for 2010-11 to shuttle equipment to Pine Island Glacier using tractors and sleds across 700 kilometers of ice and snow for a helicopter field camp. Robert Bindschadler, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center “No one knows why [the glacier] is moving so fast. No one knows what the under-shelf topography looks like. There’s a lot of interest to go out there,” noted Naughton, who has a background in construction and science. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the Pine Island Glacier camp — once we get everything out there — if it stays out there for more than two years,” he added. “The helos are currently planned for just two field seasons. … Woody [Haywood] and I are firm believers that if you build it they will come. It’s unexplored out there, and it’s pushing the logistics chain out of McMurdo.” Haywood is the supervisor of Science Construction for RPSC’s Facilities, Engineering, Maintenance and Construction department. It will be up to his team to build the camps at PIG and Byrd, the former more than 2,000 kilometers from McMurdo. “For us, in terms of what I’m used to, this is pretty far out there,” said Haywood, who has worked with the USAP on and off for two decades and was in charge of constructing a large field camp last year in East Antarctica. [See related stories: Field of dreams, Alps in Antarctica and Mountainous mystery.] “You can have 20 to 30 people working really hard at varying stages to assemble the whole thing,” he added, which include not just his team of trades people like carpenters and electricians, but the camp staff, and cargo and fuel specialists. “Every camp [put-in] is different based on how far away it is, how intense the flight logistics are, how much fuel they need and heavy equipment.” While the plan is still in flux for Byrd, RPSC planners expect to have the main parts of the camp in place in about three weeks — an impressive feat given the remoteness and weather conditions even in the Antarctic summer. “We strive for that efficiency,” Haywood said. “All the components are planned with gaining efficiencies in mind. The buildings are modular, so they’re easy to ship, store and set up. They’re also modular because the camp designs change.” Noted Naughton, “If you think about it, it’s pretty amazing. When you think about where it is in the world — the military probably doesn’t put up camps that fast in remote places. For a bunch of Antarctic hands to do it in 2 ½ weeks is pretty impressive.” The team will enjoy the relative luxury of having another large field camp — WAIS Divide, an established field camp and site of an ice-core drilling project — only 160 kilometers away. [See related story: Deep into WAIS Divide.] In fact, Byrd construction hinges on the WAIS Divide camp because the New York Air National Guard “We’re basically going to use WAIS as our beachhead to fly in the heavy equipment and re-assemble it. Having WAIS operational will drive the timeline,” Haywood said. “In my experience, this season we will have the most large deep-field camps we’ve had at one time.” Naughton said there were several reasons the NSF decided to opt for re-establishing Bryd rather than trying to use WAIS Divide as the waypoint to Pine Island Glacier. “In order to support the science, WAIS Divide would have had to have over 80 LC-130 missions land, and that is completely unrealistic. “You can’t have a hundred people at a field camp. It’s mayhem. It’s a population issue, it’s a safety issue,” he added, explaining that thinning the resources at WAIS Divide could possibly affect its science mission — extraction of a 3.5-kilometer-long ice core. Byrd will support its own science missions. One involves scientists making aerial and ground surveys of the ice sheet using instruments developed by the Center for Remote Sensing of Ice Sheets (CReSIS) Naughton said that it’s not particularly difficult to plan an operation like Byrd Surface Camp. The key is to understand what everyone needs to make the season successful. “The plan evolves as you learn the requirements,” he said. “You can share that with everyone, then people get into the details, and then you figure it out. That’s what I love about this stuff. It’s fun. You get to be creative and figure out new ways to do things.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |