|

Page 2/2 - Posted November 26, 2008

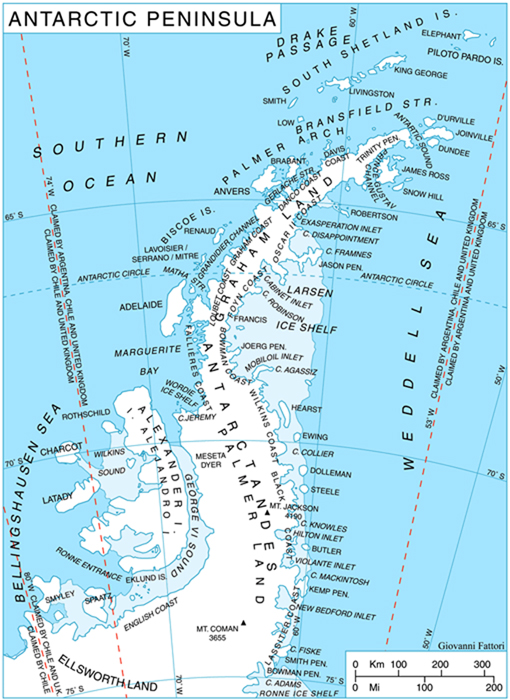

Peninsula camps offer challenges and rewardsRoss MacPhee “I work a lot in the Arctic … but it’s nothing compared to setting up camp in the extreme south,” MacPhee says. “In both places, I work in the summer, but in the Arctic, summer is really summer. There’s not a lot of snow, and it’s actually quite pleasant.” The scientists only had two good days of weather — the day they arrived and the day they left. “In between, it was pretty miserable in terms of these storm fronts coming in one after another,” he says. The team will arrive later in the austral summer this year at the same location, hoping for better weather. “One of the big areas of special projects activity is paleontology because some of those islands off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula are true hotbeds of Antarctic paleontology, and they’re kind of hard to get to,” says Evans, who has a background in geology. On the Peninsula

The draw at Livingston and King George islands for biologists like Wayne Trivelpiece His wife and co-principal investigator, Susan Trivelpiece “After all these years, it runs pretty smoothly,” Susan Trivelpiece says, “thanks in large part to John, who has done it for so many years now.” The grantees, particularly newcomers to the USAP, learn to appreciate even the oddest bits of advice from Evans. Joe Kirschvink Good advice, it turned out. Back in South America, lugging a crateful of rocks, the scientists had to unpack all the rocks and remove them from the wood crate on the orders by customs agents in Chile. “It’s funny; John Evans had this incredible intuition,” Kirschvink says. “If we hadn’t had those extra bags we would have been carrying rocks one by one.” Kirschvink and his colleagues will return to the peninsula this season, to James Ross Island, for a project that may challenge the well-established impact theory that an asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. It could be that climate change had a larger role to play. [See story: What killed the dinosaurs?] Despite the challenging conditions and fickle weather, Evans says the Gould’s crew has always managed to make landfall, though sometimes plans change. For instance, the Kirschvink and MacPhee projects will share the same science cruise. Evans scheduled the James Ross Island stop first, because that one is trickier in terms of ice and weather.

Photo Credit: Melissa Rider

Scientists search for dinosaur fossils on James Ross Island during a previous expedition.

“If it looks like they have a chance to get in to James Ross, they should shoot right over there and do it,” he says. If not, the ship will cruise to Livingston Island and then back to James Ross for a second try. “If you can’t get ashore, you can’t do your work,” Evans says. “That’s never happened, but it’s never far from the back of the mind of the people that are doing it. An icebreaker is kind of a challenging way to try to get to some of these places. Some of the islands you just can’t land on.” Mike Goebel Big or small, the Gould’s crew usually finds a way to shuttle needed equipment and supplies to the islands. Personnel have even transported all-terrain vehicles (ATV) to and from the islands. Getting the ATV on the Zodiac wasn’t difficult using the ship’s crane, but reloading it onto the boat from the island required a bit more ingenuity. In the end, the crew deflated the Zodiac, rode the ATV on the small boat, and then refilled it using scuba tanks. “The whole concept [behind special projects] is that there is so little infrastructure on the peninsula side,” Evans notes. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |