Page 2/3 - Posted July 18, 2014

Age of satellitesThe satellite imagery employed by the PGC is accurate to a few meters and has a spatial resolution of a half-meter, meaning that anything that size or larger should be discernible. About 90 percent of Antarctica has been shot by commercial satellites at that resolution, and PGC is building mosaics and applications to display that imagery. PGC develops maps for U.S. Antarctic Program “We realized that to do the cartography accurately and automatically, we had to improve the location of the names,” Herried said. “Now that we’re in this age of higher-tech mapping with higher-precision data, it’s absolutely important that these names are correct for several reasons.” First, there’s the earnest desire to make better maps. Second, the Antarctic gazetteer represents official U.S. place names, so it’s important to get them right, Herried said. Accuracy is also important for planning purposes, as well as search and rescue efforts. A rescue party searching for a person stranded near a named ridge, for example, might look in the wrong place if the coordinates in a database associated with the feature relayed by the lost party are grossly inaccurate. PGC has collaborated internationally to correct locations for names that are shared by the larger community, according to Herried. For example, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) “We weren’t tackling this just by ourselves. It was an international initiative under the auspices of SCAR,” he said.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

Blood Falls in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a name commonly used to describe the feature on Taylor Glacier. It was adopted by ACAN into the U.S. gazetteer earlier this year.

Standard of common useThe United States divides geographic names of features into two broad categories: names that honor people or organizations, and non-personal names that often are descriptive in nature or commemorate some prior event. Features have traditionally been grouped into three orders of magnitude: First-order features include regions, seas, and extensive mountain ranges. Second-order features include peninsulas, prominent mountains or groups of mountains and major glaciers. Meanwhile, third-order features include minor mountains or groups of mountains, glaciers and valleys, cliffs and nunataks. For all practical purposes, all first-order features and most second-order features have been named. A geologist by training, Borg said there are still features to be named. “As there’s a need for greater granularity in describing the landscape, there’s going to be a drive to name things. It is scale dependent,” he explained. In April 2014, ACAN recommended that the U.S. Board of Geographic Names adopt a dozen names in the McMurdo Dry Valleys and Antarctic Peninsula regions that were already in common use. Common use is based on the extent to which usage has become established by those working in a particular area. One example is the feature known as Blood Falls

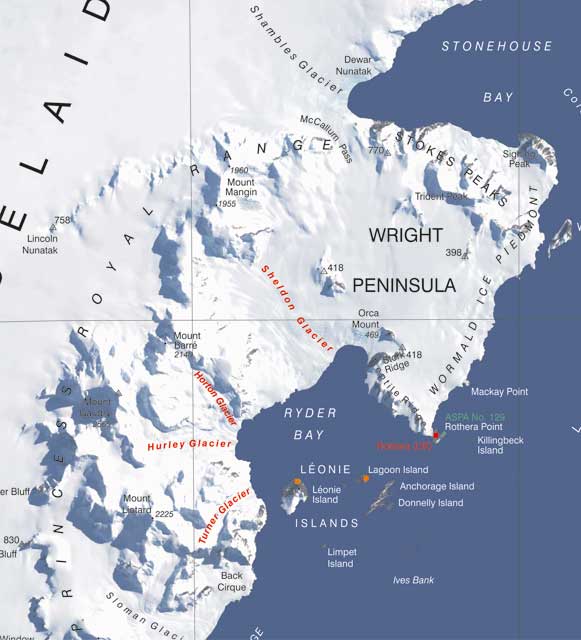

Photo Credit: UK Antarctic Place-names website

A series of glaciers near the UK's Rothera Station are named after British support personnel who worked in the region mainly in the 1970s. The British, like the Americans, have raised the bar on using personal names for geographic features in Antarctica.

Significant contribution requiredIn addition to common use, one of the other main criteria under U.S. policy involves appropriateness, which has resulted in “raising the bar,” as Borg has explained. The contribution of an individual or organization must be significant, according to the policy. “A significant contribution is characterized by some particularly outstanding and noteworthy accomplishment that would not have been possible without the actions of the intended honoree,” the policy states. Examples include major scientific discoveries or career-long contributions to advancing Antarctic research. Other noteworthy contributions that might earn one a place on the Antarctic map include areas of public policy and education. Borg said ACAN receives up to 30 proposals per year. “We’re returning quite a few because they’re being named after people who are still in the program and quite active,” he said. “They’re good people. They’re doing their job, and they’re doing it well, but it’s really got to be something significant that goes beyond that.” Place-naming after living people is a difficult issue, agreed Fox, head of BAS’s Mapping and Geographic Information Centre “The proposal has to show how the individual has made a significant contribution to Antarctic science, logistics or wider affairs such as policy, and the person usually has to have an association with the area of the name,” he said by e-mail. Recent examples include Riley and Hunter peaks in the Sweeney Mountains, named after BAS geologists who did pioneering work in the area. Features under UK policy can also be named after significant British figures, such as the well-known naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough, who was honored with Attenborough Strait. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |