|

Alps in AntarcticaInternational team maps subglacial mountain rangePosted February 27, 2009

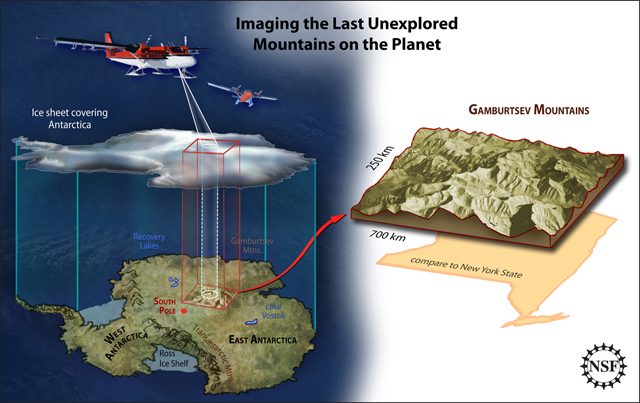

A U.S.-led international team of scientists has created the first detailed picture of a rugged mountain range buried under more than 4 kilometers of ice in East Antarctica. The researchers, based in two field camps on the high-altitude polar plateau, used twin-engine light aircraft to conduct an aerogeophysical survey of roughly 2 million square kilometers of the ice sheet, the equivalent of two trips around the globe. More Information

NSF Press Release

Previous Sun coverage: ♦Mountainous mystery ♦Prepping for science ♦Dropping off supplies The team also established a network of seismic instruments across an area the size of Texas.The instruments provide information on the structure of the mantle and crust beneath the mountains to learn more about the history of the subglacial range. The researchers suspect the mountain range served as the nucleation point for the massive East Antarctic Ice Sheet. “Working cooperatively in some of the harshest conditions imaginable, all the while working in temperatures that averaged minus 30 degrees Celsius, our seven-nation team has produced detailed images of [the] last unexplored mountain range on Earth,” said Michael Studinger, of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory “As our two survey aircraft flew over the flat white ice sheet, the instrumentation revealed a remarkably rugged terrain with deeply etched valleys and very steep mountain peaks,” added Studinger, the co-leader of the U.S. portion of the Antarctica's Gamburstev Province (AGAP) The initial AGAP findings raise additional questions about the role of the Gamburtsevs in birthing the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, which extends over more than 10 million square kilometers atop the bedrock of Antarctica, said geophysicist Fausto Ferraccioli, of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) “We now know that not only are the mountains the size of the European Alps but they also have similar peaks and valleys,” he said. “But this adds even more mystery about how the vast East Antarctic Ice Sheet formed.” “If the ice sheet grew slowly, then we would expect to see the mountains eroded into a plateau shape. But the presence of peaks and valleys could suggest that the ice sheet formed quickly — we just don't know,” he added. “Our big challenge now is to dive into the data to get a better understanding of what happened” millions of years ago. The initial data also appear to confirm earlier findings that a vast aquatic system of lakes and rivers exists beneath the ice sheet of Antarctica, a continent that is the size of the United States and Mexico combined. “The radar mounted on the wings of the aircraft transmitted energy through the thick ice and let us know that it was much warmer at the base of the ice sheet,” explained Robin Bell The scientists are particularly interested in the effect the subglacial aquatic system has on the dynamics of ice sheets, because the presence of water lubricates the ice and speeds its flow. That’s a key parameter in nailing down predictions on future sea-level rise. The most recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) The data also will be used to help locate where the world’s oldest ice is located, possibly for a future ice-coring project. Scientists estimate the ice at the bottom of the ice sheet could be 1 million years old. The oldest ice core recovered to date is about 800,000 years old. The AGAP discoveries took place during fieldwork in December and January, near the official conclusion of the International Polar Year (IPY) NSF is the lead U.S. agency for IPY, and it manages all federally funded research on the southernmost continent through the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) AGAP was fully in the spirit of IPY, noted Detlef Damaske of Germany’s Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Bell noted that AGAP is “emblematic of what the international science community can accomplish when working together.” While the planes made a series of survey flights, covering a total of 120,000 square kilometers, the seismologists flew to 26 different sites using Twin Otter aircraft equipped with skis, to install scientific equipment that will run for the next year on solar power and batteries. The seismology team — from Washington University, Penn State, IRIS, and Japan’s National Institute of Polar Research “The season was a great success,” said Douglas Wiens |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |