Cracking the caseCrevasse-riddled ice shelf poses logistical challenge for climate-change scientistsPosted October 8, 2010

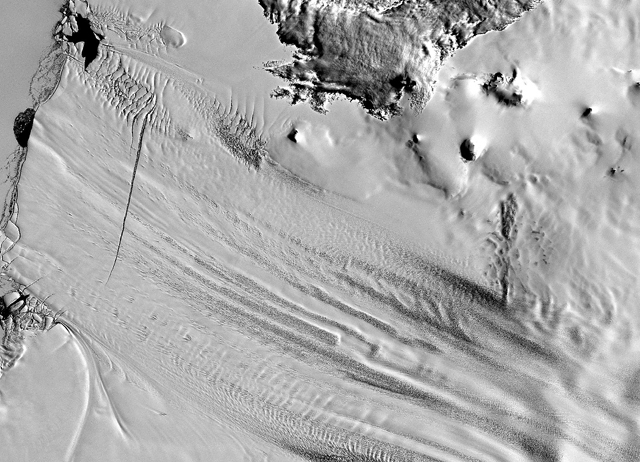

The satellite images projected onto the wall flashed through a series of photos of the Pine Island Glacier Ice Shelf, a warp speed tour through the last several years of one of the most dynamic ice regions on the planet. The last image — taken earlier this year before the sun plunged most of Antarctica into 24-hour winter darkness — left the room quiet. Several dark stripes ran the length of the ice shelf, like skid marks on snow. But those black bands aren’t tire tracks — they’re crevasses, large enough to be seen from space with high-resolution satellite imagery. And the scientists want to put several field camps amid those seemingly endless rows of fissures in the ice. “You wouldn’t want your worst enemy to go there,” noted Robert Bindschadler Bindschadler is the lead principal investigator for the two-year field project Pine Island Glacier (PIG) is the fastest flowing glacier in Antarctica, moving about 4,200 meters per year toward the edge of the continent. The ice flows into a relatively small but thick ice shelf. Thinning of that ice shelf allows the glacier to flow more quickly, ultimately adding to the global equation of sea-level rise. Bindschadler has said in the past that it is imperative that the science community understand what’s going on in this isolated region of the Amundsen Sea. “This is where all the action is taking place. We don’t have any choice in the matter. We have to go there,” he said previously. That’s proving to be quite a trick. Bindschadler became the first scientist to stand on the ice shelf in 2007 when a ski-equipped plane landed on the crevasse-ridden ice. That first and last trip to the ice shelf only lasted about 20 minutes. The ice shelf surface proved to be too hard and too rough to ensure a safe series of repeated aircraft landings needed to establish a field camp. [See previous article: Pine Island Glacier.] Plan B has required several years of patience as the logistic machine of the U.S. Antarctic Program This year several tractors will haul about 15,000 gallons of fuel and 100,000 pounds of cargo to a site near the ice shelf from another field camp called Byrd Surface Camp. That will set the stage for the 2011-12 season when Bindschadler and colleagues will be flown by helicopters from the main PIG field camp base to the ice shelf for their work. [See previous article: Byrd Camp resurfaces.] But where to deploy their instruments? That was the question facing the team as several of the principal investigators met last month on the campus of Pennsylvania State University Its defenses turned out to be more formidable, forcing the researchers to re-think the location of two field camps on the shelf itself where they’ll deploy their instruments the first year. “We’ve been overtaken by reality,” Bindschadler said. The crevasse fields aren’t the only feature of the region causing a change in strategy. This summer an international team of researchers reported in the journal Nature Geoscience that they had found a 300-meter-high ridge on the seafloor where the ice shelf was once attached. The ridge is believed to play an important role in the changes under way at the ice shelf.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |