Pine Island GlacierScientists prepare for difficult trip to Antarctica's most dynamic regionPosted July 10, 2009

More than 18 months ago, Robert Bindschadler It turned out to be the first and last flight to the floating sheet of ice for that field season. Bindschadler, along with his colleague David Holland More on PIG

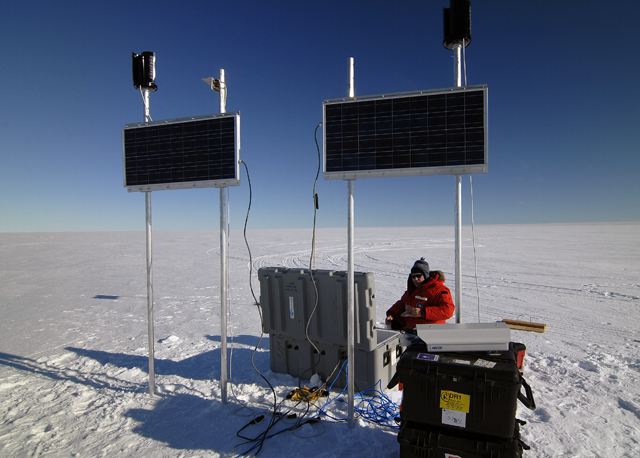

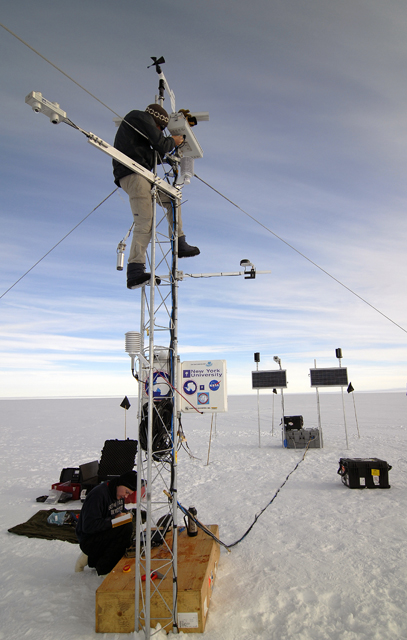

Nearly a third of the ice in West Antarctica drains through the region. Were it to all pour out in a catastrophic uncorking, sea level would rise more than a meter, enough to drown coastal areas from Florida to Bangladesh. In the immediate future — over the next century — scientists are sure Pine Island Glacier, referred to as PIG, will contribute significantly to sea level rise. Just how much remains the big question drawing them to that remote corner of the continent. “We’re going out to this difficult-to-get-to, hard-to-operate-in area because that’s where dramatic things are happening,” explained Bindschadler, chief scientist of the Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center “This is where satellite observations are setting off sirens and raising red flags,” added Bindschadler, the principal investigator for the multi-disciplinary project Despite landing on the ice shelf with a ski-equipped Twin Otter, the surface proved to be too hard and too rough to ensure a safe series of repeated aircraft landings. The National Science Foundation-funded “It was a crushing blow,” Bindschadler said. “On the fly we had to make up a different field program, at least for that season.” Convinced it would still be possible to work on the ice shelf in the future, and motivated by the unanswered scientific questions, the researchers installed an automatic weather station (AWS) near the glacier to monitor the weather and two GPS units on ice streams feeding Pine Island Glacier to track the speed of the ice toward the ocean. More than a year later, the AWS still works, shutting down only occasionally in the winter when intense storms cause icing to block the satellite communications. The information it has sent via Iridium satellites confirms that this part of West Antarctica is a common target of storms, with an annual snow accumulation of about a meter. “That’s the beginning of getting important, meaningful data,” noted Holland, a co-principal investigator and director of the Center for Atmosphere Ocean Science at New York University The road back to PIGThe road back to PIG for Bindschadler, Holland and their colleagues goes through Byrd — a former field camp and research station of the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) The plan is to construct the facilities at Byrd Camp this year and to transport all of the equipment for a second field camp at PIG, according to Chad Naughton, a Science Planning manager for Raytheon Polar Services Co. (RPSC) Tractors and sleds will haul all of the equipment needed to establish a camp near the ice shelf in 2010-11, traversing about 700 kilometers of snow and ice twice in one season. “Everything will be out there,” Naughton said. In addition, LC-130 ski-equipped planes flown by the New York Air National Guard The helicopters will solve the problem of landing safely on the PIG ice shelf, an 800-square-kilometer slab of ice that floats on an eponymous bay that opens up into the Amundsen Sea. The helicopter camp will be about 2,000 kilometers from McMurdo Station “I know we’re at the cutting edge of science, but we’re also at the far edge of logistics,” Bindschadler said.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |