|

Page 2/2 - Posted July 10, 2009

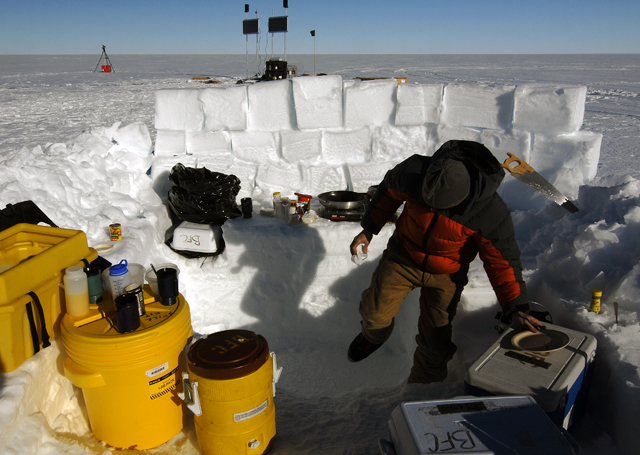

Down the holeThe scientists are still more than two years away from setting their boots back on the ice shelf, where they face a sort of Mission Impossible operation, even after many years of planning and thousands of kilometers of travel. To see below the ice shelf and into the ocean, they must use a hotwater drill to bore a narrow, 14-centimeter-diameter hole about 500 meters or more through the ice. First, they’ll send a camera down the hole to look at the ice cavity. After retrieving the camera, they’ll widen the hole to send an ocean profiling instrument down into this hidden realm. The profiler will move vertically up and down on a cable through the entire water column to measure and monitor the complex ocean currents drawing warm, deep water onto the continental shelf, across the Amundsen Sea and then beneath the underside of the ice shelf. “It’s a very, very deep, tiny little hole,” mused Tim Stanton, whose Ocean Turbulence Laboratory in the Oceanography Department at the Naval Postgraduate School Eventually, the scientists plan to deploy four ocean profilers over two field seasons beginning in 2011-12. Aside from six forays under the ice shelf by a robotic sub earlier this year by researchers collaborating with the PIG investigators, the information gleaned from the profilers will be among the first measurements of the ocean cavity. “Anything we find will be a step forward,” Stanton said. The first biteThe researchers won’t be idle for the next two years. This coming field season Holland will return to the instruments he set up in 2007-08 to perform maintenance, and to install three additional AWS systems for scientific and logistics purposes. A separate team will work at a spot called Windless Bight on the Ross Ice Shelf near McMurdo Station to test the drilling and ocean profiler systems. “The tolerances on this are so tight, we feel it warrants testing — what I call the choreography of all this,” Bindschadler said. “We don’t have much time to pull the hotwater drill hose out and get the profiler down. We’ve got one shot at doing it. If it gets stuck, there are going to be a lot of unhappy people.” Bindschadler noted that the profiler, while proven technology, has never been put together in the configuration required to squeeze down the long rabbit hole at PIG. While the ice shelf at Windless Bight is perhaps only 100 meters at its thickest point, the operation is important to bring the entire team together to not only rehearse each person’s role but to build cohesion among the members, according to Bindschadler. “Part of the practice is to live together at a field camp and eat each other’s cooking,” he said of the two- to three-week expedition. “We will learn a lot in that process and come together as a scientific team, I have no doubt.” Bindschadler said the team hopes to get some meaningful data out of the test as well. “The profiler will have some interesting ocean conditions to profile. It won’t just be a test of the choreography,” he added. “There actually will be some interesting data come from this that will tell oceanographers how the water circulates around Ross Island and the ice shelf.” Meanwhile, Holland expects to spend about two weeks at Byrd and smaller field camps in the backcountry of West Antarctica setting up the AWS systems to help with flight operations and to monitor weather over the Amundsen Sea. That information is important for the models that he and others will eventually develop to help explain and predict the ocean, atmosphere and ice processes in that dynamic region. Holland said he is hopeful to finish his job in about two weeks, but based on his previous field experience in West Antarctica, he takes a philosophical approach to the work. “There are many complications that cause one to spend a great amount of time at these camps eating vast amounts of chocolate,” he said. “It’s a logistics challenge and it’s a science challenge, and success is guaranteed in neither.” NSF-funded research in this story: Robert Bindschadler and Alberto Behar, Goddard Space Flight Center, Award No. 0732906 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |