|

Money well spentToday, the ice core team led by Thompson and his colleague and wife, Ellen Mosley-Thompson, boasts state-of-the-art equipment at the Byrd Polar Research Center. The facilities include a Class 100 Clean Room, which contains less than 100 particles per cubic foot of air, where researchers, clad in all-white garb with white hoods like a nun’s habit, study ice samples. A cold storage facility, kept at about minus 40 degrees Celsius, houses about 7,000 meters of ice cores. But times were hard when Thompson first proposed to the National Science Foundation (NSF) The scientists wanted to take ice cores from the Quelccaya ice cap in the Peruvian Andes, to connect the ice data from the Antarctic and Arctic with something in the middle of the planet. Thompson and Mercer showed Jay Zwally at the NSF aerial photos of Quelccaya and outlined their plan for a reconnaissance mission. Zwally said he was intrigued, but Peru was out of the scope of the OPP.

Photo Courtesy: Lonnie Thompson/OSU

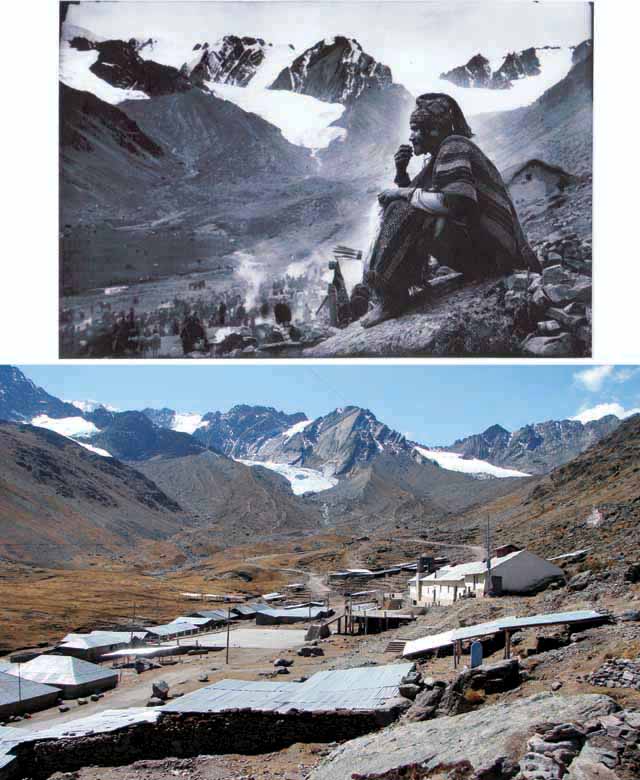

Above, an image taken by a Peruvian photographer in the 1930s shows the extent of coverage of several Andean glaciers. Below, the modern image shows the ice floes as they are today.

The opportunity apparently lost, Thompson headed to Byrd Station in Antarctica during the 1973-74 summer season. Toward the end of his fieldwork, he received a telex from Zwally, who said he had funded all of his polar projects — and had $7,000 left. As Thompson tells the story, Zwally asked, “What could you do on that tropical glacier for $7,000?” Thompson quickly responded, “‘I think we can get there.’ … The next summer, that’s what we did.” Never mind that Thompson had little practical mountaineering experience (and has often said he’s not particularly fond of recreational hiking and climbing). Nor the fact that no one had tried to haul tons of ice coring equipment up towering mountains and return back with ice. But Thompson — standing on the summit of the Quelccaya ice cap in 1974 with Mercer, Chilean glaciologist Cedomir Marangunic, and Canadian mountaineer John Ricker — knew there was a unique treasure before him. “Sure enough, it was clear there was a record, but getting that record was going to be a challenge because it was a two-day journey from the end of the nearest road to the margin of that ice field,” he recalls. The exploratory trip led to a full-on expedition in 1979. But the team went in heavy, assuming drilling for core in the mountains would be like working on an ice sheet in Greenland or West Antarctica. Thompson and his team had hoped to transport the drill equipment and generator aboard a helicopter. But the machine had a maddening (and no doubt sickening) propensity to free-fall around 19,000 feet. In the end, the researchers lowered themselves by ropes down the wall of the ice and sampled to the bottom of a 25-meter crevasse, returning with a perfectly preserved, 25-year record of El Niño, with the research later published in the journal Science. But the small samples were merely unsatisfying appetizers for Thompson. “I was just really discouraged,” he says. “At that stage we were either going to have to give up or find a new way to drill.” They did the latter. Working with Bruce Koci, an engineer at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln “We had no porters, we had no one,” he says. “We carried everything to the summit, assembled the drill, carried the samples back down, prepared them, bottled them and shipped them out.” But they did it, drilling two holes and pulling the first deep ice core from the tropics, which required cutting the 6,000 samples of ice by handsaw. With those first samples, Thompson managed to build a 1,500-year record of tropical precipitation. The record revealed past El Niños, as well as dry periods, including evidence that that the Southern Hemisphere was cooled by the “Little Ice Age” recorded in Europe between 1500 and 1800, according to his biography published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America in 2006. “It all started on that $7,000 that was left over in 1974,” Thompson muses. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |