|

Civilization in iceOne of the intriguing things about working in the tropics is that you’re often working where civilization started, Thompson points out. It seems that weather and climate have always been a topic of conversation since time immemorial. “You can see some of the [climatic] events that are recorded in the hieroglyphics on the tombs of the pharaohs in the ice itself,” Thompson explains excitedly. “That’s really striking that you can actually do those things.” For example, in ice recovered from the Himalayas at some 23,000 feet, scientists can see the telltale signs of a monster monsoon that killed 700,000 people in central India in 1790 from increased dust and enriched oxygen isotopes. By tracking powerful storms like these back through time, researchers can determine how often they naturally occur — and whether human-induced climate change may be fiddling with natural variability. In several recent ice cores drilled to the bedrock from the Naimona'nyi ice field in the western Tibetan Himalayas at about 6,100 meters, a more sobering fingerprint of human civilization helps date the records — thermonuclear tests from the 1950s and 1960s, particularly the U.S. Castle Bravo test in 1954 on Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands. “Those become timelines because we know exactly when the tests took place. We find that you can determine the accumulation rate for this area since 1963 or 1951,” Thompson says. “We’ve done that across China.” And what they’re finding from those radioactive layers is that there’s been little if any net accumulation in the last half-century. The 58 glaciers on Naimona'nyi once covered an area ten times greater than today.

Photo Credit: Lonnie Thompson/OSU

Nearly 100 porters were needed to carry drilling equipment from the end of the road to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro in 2002.

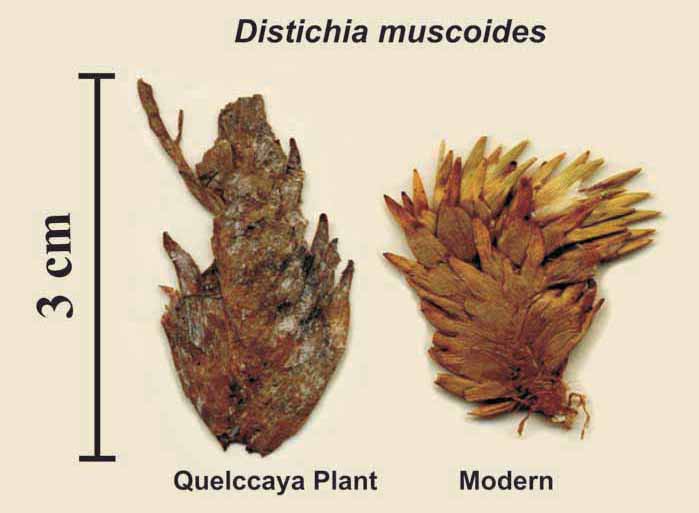

“They’re very important for water supplies in these areas, and that’s especially true in the dry season,” Thompson says. “That’s true whether you’re looking at glaciers in the Himalayas or down through the Andes. There’s a very direct link to people, to hydroelectric power production, to irrigation, to municipal water supplies.” Indeed, Thompson talks about people as much as he does the science behind his work. A favorite story seems to be about an expedition to Sajama, Bolivia. At the base of the mountain where the team hoped to drill into the glacier on the summit was a village, whose permission they needed before beginning their work. Thompson made a four-hour presentation of what the scientists proposed to do and why. But the village medicine woman considered the idea a bad omen. “She was absolutely sure that drilling these glaciers was going to anger the gods,” Thompson says. To appease the gods — and maintain good relations with the villagers, always a priority — Thompson agreed to donate $500 to the library and to hire local people for labor (already in the plan). Additionally, the ice core team participated in the sacrifice of an alpaca to ask forgiveness of the gods. In the end, the gods were happy, the villagers were happy, and Thompson got his ice cores. “All of the projects have a story, the challenge of how you get into these areas and how you get the cores out,” he says. “And all of them have stories about how incredibly supportive people are, in places where you have only met them, and they want to help you with your job. Without them, we wouldn’t have accomplished any of this. “At the end of the day, you’re a guest.” The story continuesThe next chapter in the story goes back to the beginning, to Peru and the Quelccaya ice field, when a team from Byrd Polar returns to the region this summer. Thompson and team have made several trips to the glacier in the last 35 years, like a doctor making repeated house calls to a sick patient. In this case, the fever is causing the 160-meter-deep ice cap to melt away. In the wake of the glacier’s retreat in 2002, the researchers found a perfectly preserved wetland plant. Carbon dating tests indicated the plant had been buried in the ice for about 5,200 years. That suggests that the climate had shifted suddenly to capture the plant and preserve it without killing it. The date is significant because other abrupt changes in climate from around the world — such as the shift of the Sahara from a habitable region to a barren desert — also occurred around the same time. Thompson doesn’t know what happened to cause a plant to freeze in time, but one hypothesis is that fluctuations in solar output may be to blame. Evidence shows that about 5,200 years ago, solar energy from the sun dropped sharply and then surged over a short period. This huge flux may have triggered unusually strong winters in Peru that suddenly buried plants in snow and droughts that laid waste to the Sahara. The mystery is on the top of Thompson’s scientific agenda, particularly if human-induced climate change is bringing us closer to some sort of similar tipping point. Figure out what happened five millennia ago, and you may have a crystal ball into the future. But time is running out; the clues in the mystery are disappearing. By the end of the century, Thompson says, most of the world’s tropical and subtropical ice will vanish. “It will be gone. And history will be gone,” he says. [Editor’s Note: For more about Thompson and his quest to recover ice cores from around the world, check out Mark Bowen’s book, “Thin Ice: Unlocking the Secrets of Climate in the World’s Highest Mountains.”

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |