|

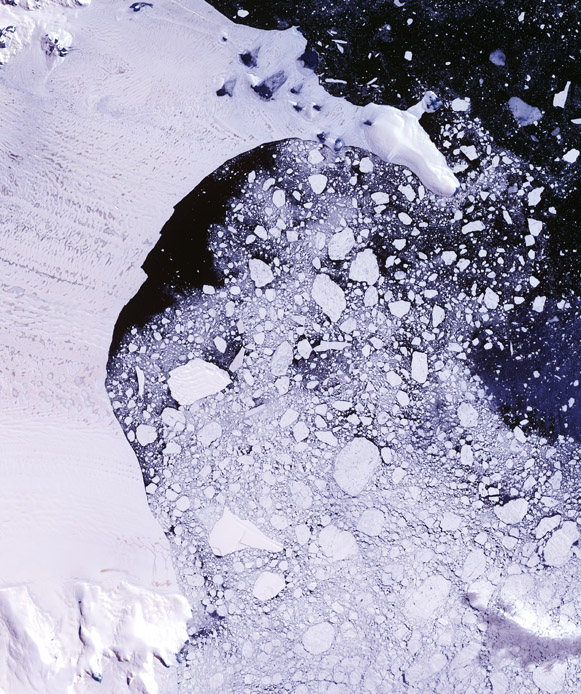

Overwhelming changesIncreased ice loss in Antarctica, Greenland has scientists worriedPosted October 3, 2008

Urgency. It’s in their words, their proclamations, and the data from their research. Greenland and parts of Antarctica are losing ice due to human-induced climate change, causing global sea level to rise. There is not panic, only sobering statistics from Konrad Steffen and Eric Rignot, who are leading a project to study the Larsen C Ice Shelf along the Antarctic Peninsula before it cracks and shatters apart like others in the region. [See related story: House call.] Director of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) “We should have more warming now, not based on models but based on simple principles,” he observed. It turns out that while greenhouse gases were trapping heat as humans pumped them ever more rapidly into the atmosphere during the last century, emissions of anthropogenic sulfur compounds and subsequent aerosol formation were working to the opposite effect — reflecting solar energy back into space. “It was the global dimming that was masking it,” Steffen said. In effect, all the polluting of years past that brought acid rain also bought the planet a reprieve from the heat-trapping gases. But since about 1990, thanks to the Clean Air Act and other national and international legislation and agreements, the air has cleared. More solar energy is reaching the Earth — and becoming trapped in the atmosphere. “That was one of the reasons we couldn’t see the greenhouse effect earlier. It should have occurred in the 70s and 80s already,” Steffen said. Few would argue that changes are under way now, though some are still skeptical that humans are the primary cause, believing instead that the climate is naturally warming. However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Even Antarctica is responding, particularly its western half, a marine-based ice sheet. A professor of Earth system science at the University of California-Irvine Rignot’s team estimated changes in Antarctica’s ice mass between 1996 and 2006 and mapped patterns of ice loss on a glacier-by-glacier basis. They reported that it lost enough ice to raise global sea level by 0.3 millimeters a year in 1996 to 0.5 millimeters a year in 2006. [See orginal NASA article Together, Greenland and West Antarctica could raise sea level from anywhere between 10 and 15 meters if all the ice drained into the ocean. “From the scientific viewpoint, I don’t think one region is more important than the other. They both require more attention,” Rignot said. “For the most part, we are overwhelmed by the changes taking place in these regions. That’s a source of concern if we want to make significant progress … to predict what these ice sheets will do in the coming decades. “The International Polar Year And such changes are likely only beginning. Steffen noted carbon dioxide emitted today will remain in the atmosphere for several centuries. He poses a rhetorical question: Whatever we do now to remediate the effects won’t have an immediate effect, so why do it? “We do it for the future, future, future generations, and it starts with our kids,” he said. “It is time to act, because it is going faster and faster.” Forget for a moment about 10 meters of sea level change. Most experts will say that’s still hundreds of years in the future. The IPCC’s worse case scenario for 2100 is about a half-meter of sea level rise. Rignot said that number is too conservative, and does not account for the relatively hard-charging glaciers of recent years. “What we see today is that glacier response is really dominating the response of these ice sheets,” he explained. A more realistic estimate is at least double the IPCC estimate, according to the scientists. Two meters is not unrealistic but more uncertain at this time. “That’s when it gets scary when you say two or three times [the IPCC estimate],” Steffen said. “That puts New York under water for any ongoing storm. Still a lot of time, a hundred years, you think, but it’s not. Time goes fast.” Societies have been able to work together previously to address global environmental problems, such as ozone depletion and acid rain. Steffen said climate change requires a similar response. “That’s why I’m quite confident,” he said. “We were able to counteract the sulfur. In the longer term, I’m quite confident we’ll be able to move ahead into an alternative way of energy.” NSF-funded research in this story: Konrad Steffen, CIRES; Eric Rignot, UCI and NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Award no. 0432946 Return to main story: House call. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |