Turning over an old leafPaleobotanists reconstruct Triassic with fossilized plant materialPosted April 22, 2011

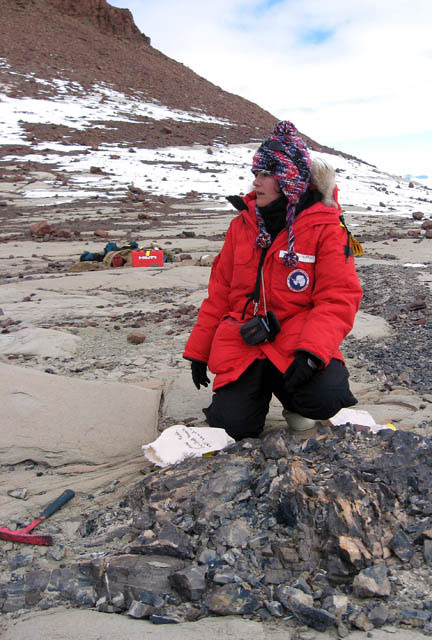

Eight years ago, when paleobotanists Edith and Tom Taylor In the field season just ended, the Taylors packed it in a couple of days early, hauling some 5,000 kilograms of rock back to the University of Kansas “It’s been the most productive year that we’ve ever had since we’ve been down here,” said Tom Taylor, who has made four trips to the region in the last quarter-century, among other expeditions to Antarctica. “It’s been an incredible season for us.” The last fossils are en route this evening, with several team members arriving via helicopter from the Gordon Valley. It’s an area where the Taylors have enjoyed considerable success in their decades-long work to understand the evolution of the flora that once dominated Antarctica more than 200 million years ago. The paleoforest in Gordon Valley thrived in the Middle Triassic, with 99 preserved seed-fern tree trunks previously documented, some trunks nearly a meter above the ground. The trees themselves grew up to 20 meters in height along what were likely the banks of an ancient river system. The site is so unique that the Taylors hope to gain a special designation under the Antarctic Treaty Evolving picture of plant historyThe Taylors and the paleontologists, geologists, sedimentologists and others who have worked in these mountains on timescales that stretch from the middle of the Paleozoic to the middle of the Mesozoic eras have pieced together a still-evolving puzzle of the continent. It’s a stretch of planetary history that covers the arrival of proto-mammals and the extinction of the dinosaurs. The southern continents of Pangaea, still glued together, stretched apart. Icehouse melted into greenhouse, for any number of reasons. Take your pick: carbon dioxide, volcanism or maybe the eruption of methane hydrates from the seafloor. Along the way, today’s flowering plants evolved. And it turns out Antarctica is one of the best places to track some of the phases of this evolution thanks partly to the sheer number of fossils to be found. And, probably more importantly, to the nearly unique preservation conditions that once existed during the cooler but wetter conditions of the emerging greenhouse. “This is one of the few places in the world where there are terrestrial rocks across the boundary,” said Edith Taylor, referring to a rough stitch in time a quarter of a billion years ago when one geologic time period yielded to another — the end of the Permian and the beginning of the Triassic. The boundary marks the greatest of five mass extinctions (or six, as some scientists claim the present age is undergoing a dying-off of similar magnitude) that rocked the planet. For the Taylors and their team of fellow paleobotanists, sedimentologists and geochemists, the boundary divides the Permian Glossopterids that dominated its environment for some 40 million years from the Triassic seed ferns that followed. The Taylors and their colleagues are interested in how the various bits and pieces of the plants are put together, as well as how the plants themselves worked. In the broader picture, the researchers, with co-principal investigator John Isbell from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Remember that Antarctica’s high polar latitude changed little over tens of millions of years, as Pangaea shifted and split apart. Part of the year, the sun shone 24 hours a day. In the winter, only the moon and stars offered any light. “There is no modern analog for that,” Tom Taylor noted. “These plants had to adapt in particular ways, and that’s one of things we’re interested in. How did they do it?” The presence of cycads — seed plants with thin-walled cells that today only grow in subtropical and tropical environments — indicate that Antarctica must have had a relatively mild environment, even through the winter, according to Tom Taylor. “They would get mushy if subjected to below-freezing temperatures,” he said. Perserving the pastThe Taylors are quick to note that the age of the rock exposures alone isn’t the most fascinating thing about the Antarctic fossils. Some of the plants undergo a rare form of preservation called permineralization. This type of preservation is one in which the organic material is only filled with minerals, in this case silica, and not completely replaced. “That preservation type allows us to look at the cells and tissue systems of these plants that lived during the Permian and Triassic,” Tom Taylor said. “The preservation is worth the trip,” Edith Taylor added. What makes the finds particularly special is that they are petrified peat deposits. The Taylors liken it to turning a compost heap in your backyard to stone. This trip yielded new sites where the plants had been silicified. “This is the largest group we’ve had down here, and I think it’s really paid off,” said Tom Taylor of the 10-member-strong field team. “They’ve found this peat in nearly every spot we’ve been to.” And the new sites have provided new insight, with the discovery of plant reproductive organs that are unique to these Antarctic plant species. “Nobody has found reproductive organs like that,” said Edith Taylor. “Although you find [Glossopteris] leaves everywhere, we really know very little about the reproductive organs of the plant and how it was put together.” Putting the plants back together is a job that takes place back in the States. The lab work involves sawing the rocks with diamond blades, etching them with hydrofluoric acid, and then squirting acetone, the main ingredient in nail polish remover and paint thinner, on the surface. A piece of plastic is then rolled over the specimen, allowed to dry, and then pulled away to reveal a thin section of the plant in the rock that can be examined under a microscope. In the past, the researchers have been able to reconstruct a whole plant with that method. And with enough material for an army of PhD students to pore through over a lifetime, the Taylors expect to add a few new chapters to the story of plant evolution in Antarctica. “It’s just one of the greatest localities in the world,” Tom Taylor said.

NSF-funded research in this story: Edith and Tom Taylor, University of Kansas, Award No. 0943934 Return to CTAM 2010-11 main page. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |