Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

|

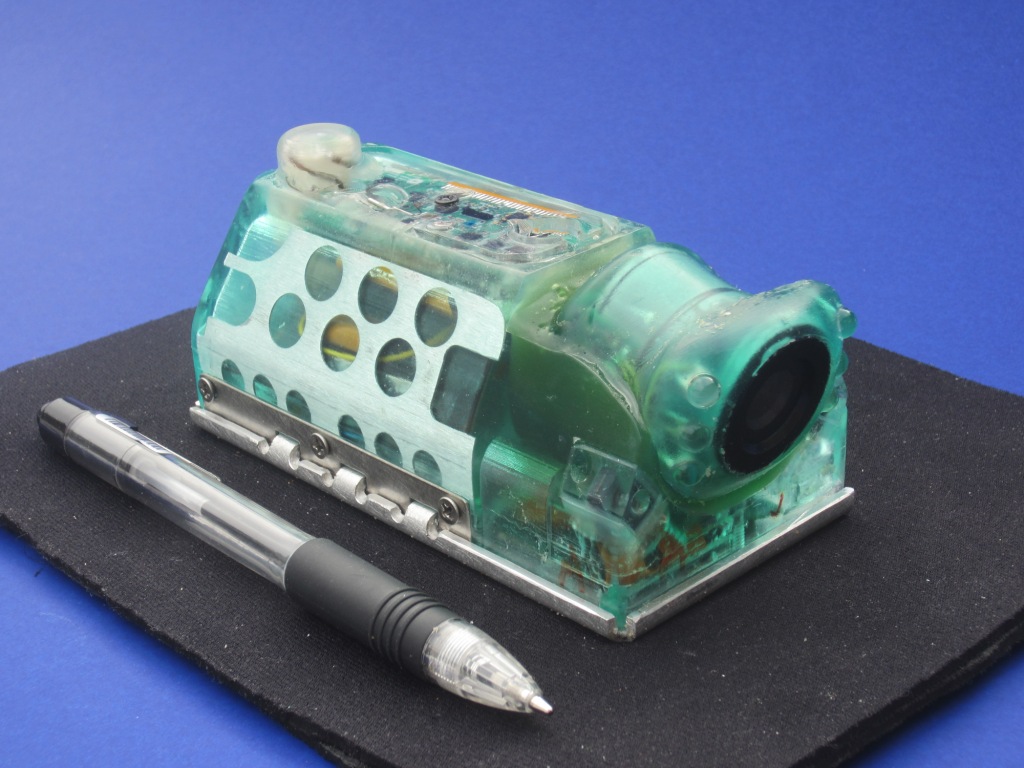

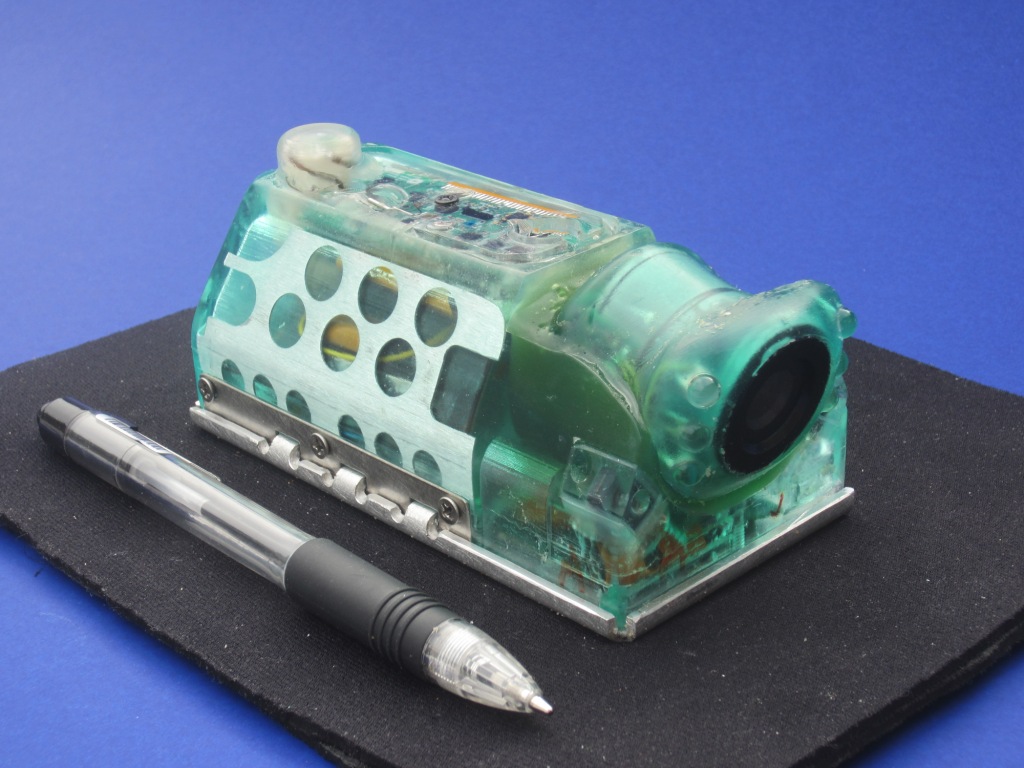

A Weddell seal outfitted with a specially designed video camera capable of recording of 27 hours of underwater

activity. Its array of sensors also records such properties as light, temperature and salinity.

|

Page 2/2 - Posted December 22, 2014

Getting hints from 3D dive profiles

There is already some tantalizing evidence this is the case.

Over the years, the team has been able to create sophisticated three-dimensional models of Weddell seal dive behavior thanks to the development of instruments that record a suite of environmental and physical data, as well as video images, that are attached to the animal’s head.

“In the late 1980s, we started playing around with an idea of putting a camera on animals, looking over their head, so we could travel with these animals vicariously to these great depths and see what they were doing – stalking, pursuing, capturing prey,” said Davis who started his career in the Antarctic as a graduate student in the 1970s.

Photo Courtesy: Randall Davis

A close-up of the fifth-generation Video and Data Recorder boasts a low-light video camera with near-infrared LEDs that can capture up to 27 hours of underwater activity.

The fifth-generation Video and Data Recorder employed for the latest project boasts a low-light video camera with near-infrared LEDs that can capture up to 27 hours of underwater activity, more than double the time of the previous model.

Its array of sensors records such properties as light, temperature and salinity. Hydrophones pick up seal vocalizations, a weird spectrum of noises that sound like special effects from a 1950s science fiction movie. Data for depth, speed and compass bearing allow the biologists to reconstruct each foray below the sea ice in such detail that they can identify prey pursuit and capture.

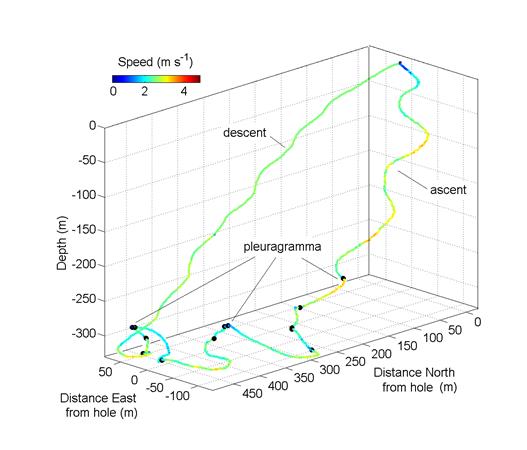

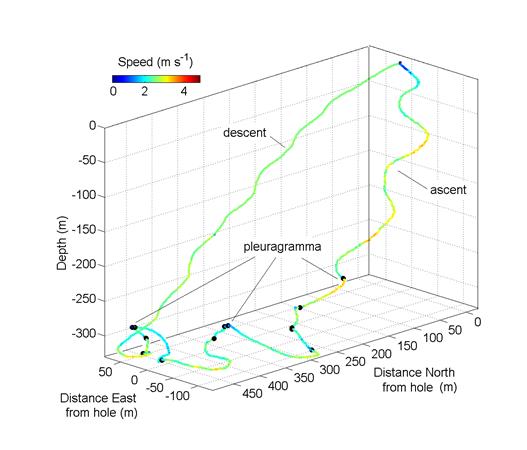

The dive profiles also revealed a sort of slalom swimming behavior that seemed reminiscent of the pattern demonstrated by Walker’s homing pigeons as they flew around magnetic lines.

Williams noted that for an animal that requires efficiency in its movement – any wasted movement represents a drain on that ‘scuba tank’ – the twisting turns the seals make while swimming would imply that indeed there may be a method to their madness.

“Navigation is costing them, and we’re going to determine how much it’s costing them to do those kinds of maneuvers,” she said.

Photo Courtesy: Randall Davis

A three-dimensional dive profile of a Weddell seal descending, capturing prey, and returning to the surface to breathe.

Getting more evidence for magnetic navigation

The behavior from the dive profiles is intriguing but not conclusive. So: How to determine whether Weddell seals, like homing pigeons, are using magnetic lines to weave their way back home?

For the next three years, the team will work with a handful of Weddell seals. Each animal will be outfitted with a Video and Data Recorder and released into three areas over the course of a couple of weeks in McMurdo Sound, where researchers have precisely mapped the magnetic field.

“There should be changes in behavior when an animal is in a different magnetic field,” Fuiman explained

In other words, comparing the magnetic anomaly maps of McMurdo Sound with dive profiles from the Video and Data Recorder should provide some answers.

“That will give us the amount of data that we need to statistically analyze the information to look for these hypothesized behaviors,” Davis said.

Next year, the group will return in August toward the end of the Antarctic winter, when there are still 24 hours of darkness. Davis said it’s possible Weddells may be using other strategies for relocating holes in the sea ice with apparent ease. One possible explanation involves the idea of piloting – using under-ice visual features, such as cracks in the ice, to navigate.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

The main field camp for the team on the sea ice..

However, without light penetrating the ice during winter darkness, the team can eliminate another factor.

“Magnetic sense isn’t the only sense that seals use for orientation,” Davis said. “What we’re trying to do is separate pilotage from navigation.”

Another sense that may be in place is hearing. Seals may be receiving acoustic cues on where breathing holes are located from other Weddells. In that case, Davis explained the team is using a directional hydrophone to pinpoint the direction of vocalization.

“Being able to travel reliably between sparsely located breathing holes is absolutely critical for their ability to live under this ice,” Davis said. “We’re trying to take away as many other potential orientation abilities of this animal and focus on this one aspect, which is the magnetic orientation.”

Previous

1

2

Next