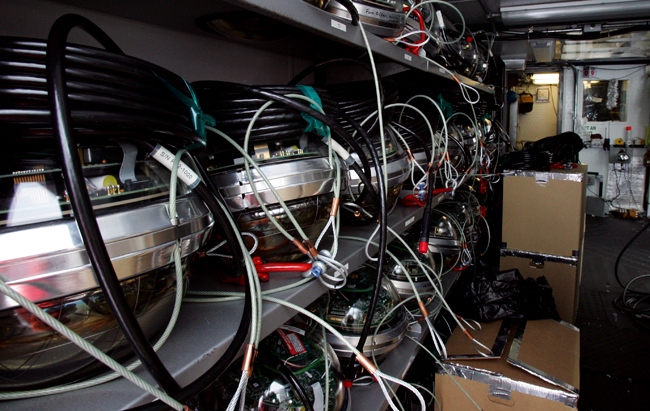

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek |

IceCube digital optical modules, also called DOMs, sit on shelves awaiting deployment down a recently drilled ice hole. The DOMs can detect the head-to-head collisions between a neutrino and an atom within the ice. |

Karle: IceCube leading the race to discover properties of cosmic neutrinos

Construction of the detector is no mean feat in itself. The IceCube camp, located a kilometer or so from the main South Pole Station building, looks like a derailed train on ice — a collection of rectangular buildings that house water tanks, generators and high-pressure heaters.

A cobweb of hoses slung between the buildings transports thousands of gallons of water through the system, which includes a Rod well, a sort of underground aquifer of water in the ice created by a heated coil. Engineers designed the system to recapture most of the water required to melt each hole, according to Australian Alan Elcheikh, IceCube’s lead driller.

Computers monitor the entire operation, tracking everything from the amount of fuel used to drill each hole (an average of 7,400 gallons last year) to the rate of drilling (about 2 meters per minute on the way down), as well as water temperature and flow.

“It’s a home-grown control system,” Elcheikh said.

The hot-water hose itself is so heavy that the drillers must tape a secondary cable to it for support as it descends slowly into the ice. A visit to the two-storey-high tower where the operation takes place found two of the drillers — Graham Tilbury and Eric “Bear” Coplin — attending to the hose and cable. Tilbury deftly cut off the thick tape as the hose and cable slowly ascended through a notch cut into a manhole-sized cover, which protects the ice hole from an errant hardhat dropping down.

An assistant at the College of Marine Science at the University of South Florida, Tilbury said he took a leave of absence from his job for the opportunity to work in Antarctica on the IceCube team. “IceCube is a tremendously cool project,” he said.

Most of this year’s drillers, Elcheikh said, have previous experience with the project or working elsewhere on the Ice. Coplin, for instance, worked several seasons at McMurdo Station before switching to IceCube.

This year’s team set a blistering pace for ice-hole drilling. Those 18 holes represent a personal best for the project, despite a late start. Improvements in technique have whittled the time required to drill a hole down to 35 hours, Karle said. Deploying a string of DOMs takes another 10 hours, he added.

“They’re an exceptionally good crew,” he said of the 30 drillers, who work in three, 10-person shifts around the clock once a hole begins. “Maybe this is the No. 1 reason for the improvement.”

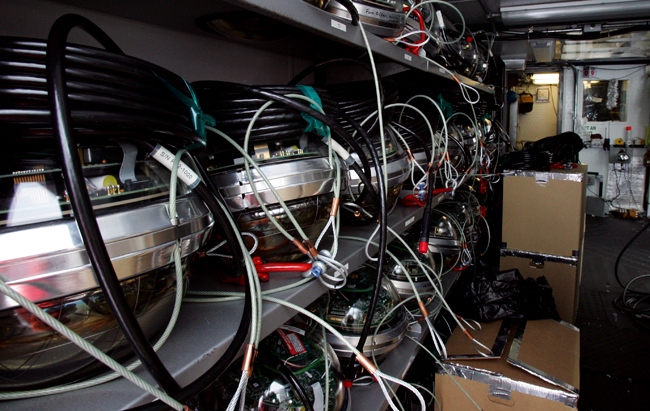

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Hoses and cables snake from one building to another in the IceCube drill camp as the water is heated up before it is pumped to the drill tower for creating a hole.

Construction is scheduled to continue through the 2010-11 summer season at South Pole. However, parts of the detectors are already working, with 22 strings taking data since May. Analysis is still ongoing, Karle said, but IceCube is already detecting one atmospheric neutrino per hour.

Those aren’t the Holy Grail neutrinos yet. “It’s too early to say anything about cosmic neutrinos,” Karle said.

IceCube isn’t the only neutrino detector on the planet. ANTARES (Astronomy with a Neutrino Telescope and Abyss environmental RESearch), is a sort of complementary neutrino telescope currently under construction in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Toulon, France.

ANTARES will attempt to capture neutrino collisions in the water as they travel through the planet from the southern hemisphere, while IceCube is actually oriented toward the northern hemisphere as neutrinos pass through the Earth.

Karle said that, while it is important to have such multiple experiments to confirm results, there is also a spirit of competition involved.

“We want to be the ones to make the discovery — absolutely,” he said. “It clearly is a race. And, at the moment, we are clearly leading the field. We want the first important discovery.”

NSF-funded research in this story: Francis Halzen, University of Wisconsin — Madison.

Back 1 2