Southern exposureScientists find further evidence that northern cold snap never touched AntarcticaPosted September 17, 2010

A sudden cold snap in the northern hemisphere about 13,000 years ago, shortly after the end of the last ice age, apparently never touched Antarctica. In fact, much of the southern half of the planet appeared to be warming up with the atmospheric increase of the heat-trapping gas carbon dioxide while the other side of the equator cooled off for about a thousand years. That’s the finding from a new study in the prestigious journal Nature that offers evidence that New Zealand was also warming in step with Antarctica. The deep-freeze that affected the northern hemisphere is known as the Younger Dryas, named after the white flower that grows near glaciers. “Glaciers in New Zealand receded dramatically at this time, suggesting that much of the southern hemisphere was warming with Antarctica,” said lead author Michael Kaplan “Knowing that the Younger Dryas cooling in the northern hemisphere was not a global event brings us closer to understanding how Earth finally came out of the ice age,” Kaplan added. Funding for the study came from the National Science Foundation’s Division of Earth Sciences The scientists estimate that New Zealand glaciers lost more than half of their extent over a thousand years as the local climate warmed by as much as 1 degree centigrade. Meanwhile, temperatures in Greenland dropped by 15 degrees centigrade, based on data from ice cores.

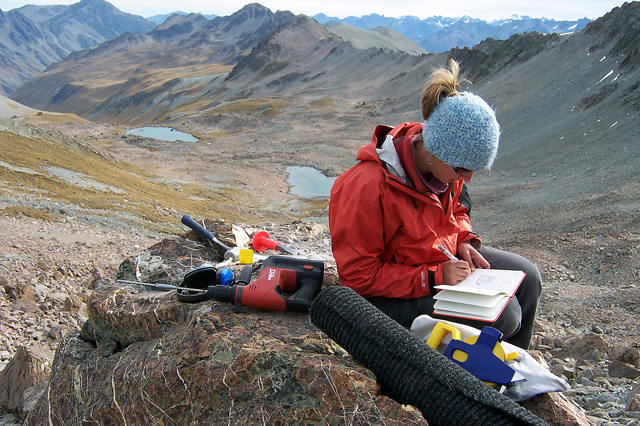

Photo Credit: Mike Kaplan

Samples were flown out of Irishman Basin by helicopter and shipped to the U.S. for analysis. To reconstruct New Zealand’s past climate, the study’s authors tracked one glacier’s retreat on the South Island’s Irishman Basin. When glaciers advance, they drag mounds of rock and dirt with them. When they retreat, cosmic rays bombard these newly exposed ridges of rock and dirt, called moraines. By crushing this material and measuring the build-up of the cosmogenic isotope beryllium-10, scientists can pinpoint when the glacier receded. The beryllium-10 method allowed the researchers to track the glacier’s retreat upslope through time and indirectly calculate how much the climate warmed. The overall trigger for the end of the last ice age, called the Last Glacial Maximum, came as Earth’s orientation toward the sun shifted about 20,000 years ago, melting the northern hemisphere’s large ice sheets. As fresh melt water flooded the northern Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf Stream weakened, driving the north back into a deep freeze. For years, scientists have tried to explain how the so-called Younger Dryas cooling fit with the simultaneous warming of Antarctica — based on data from ice cores — that eventually spread across the globe. The Nature paper discusses the two dominant explanations without taking sides, according to the press release from Columbia University’s The Earth Institute In the other, the weakened Gulf Stream triggered a global change in ocean currents, allowing warm water to pool in the south, heating up the climate. Bob Anderson “This is one of the most pressing problems in paleoclimatology, because it tells us about the fundamental processes linking climate changes in the northern and southern hemispheres,” he said. “Understanding how regional changes influence global climate will allow scientists to more accurately predict regional variations in rain and snowfall.” NSF-funded research in this story: Michael Kaplan, George Denton and Joerg Schaefer, Columbia University, Award No. 0745781 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |