Crowning achievementTop of iconic South Pole Dome hoisted into museum dedicated to Navy SeabeesPosted July 29, 2011

Lee Mattis was never meant to go to Antarctica. The job of helping oversee construction of the iconic South Pole Dome research station in the early 1970s was originally to be done by someone else. Forty years later, Mattis found himself once again raising the dome in the air — but this time at a U.S. Navy museum in Port Hueneme, Calif.

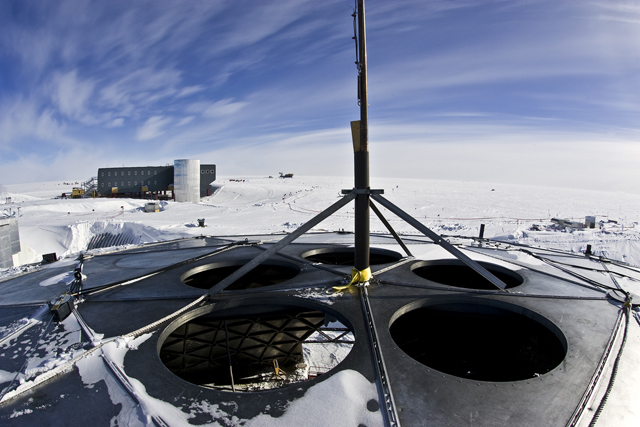

Photo Credit: Josh Landis/Antarctic Photo Library

An American flag is visible through one of the vent holes of the Dome at the South Pole.

“Some things come full circle,” mused Mattis, talking by phone after he and several others installed the top ring of the iconic dome in a new 38,000-square-foot museum dedicated to the U.S. Naval Construction Battalion Mattis was the civilian project engineer who designed the specialized erection equipment and the scheme of how to assemble the geodesic dome on ice. He spent two summer seasons at the South Pole between 1971 and 1973. It was a job and an adventure, and he had assumed that was the end of it. Until John Perry, a retired Navy officer, recruited him in 2003 to save the dome for posterity. A new and advanced research station His Antarctic experiences, which included a winter assignment in 1968, never left him. “Over the years, I was always interested in seeing how the dome was doing, how it was faring,” said Perry, 74. “We hated to see the dome destroyed. Wasn’t there something else that could be done?” Jerry Marty was also keen to save the dome. He had been a civilian contractor with the company Holmes and Narver Inc., which tackled other projects associated with the construction of the Dome Station during the 1974-75 summer season before its commissioning on Jan. 8, 1975. [For more history about the South Pole, see Bill Spindler's South Pole Station website Marty later devoted some 15 years of his life as the construction project manager to build the new South Pole Station, which was dedicated on Jan. 12, 2008. About two years after that date, the dome did come down — with care. A construction crew unraveled the 52-foot-high geodesic structure from the top down, peeling it like a giant orange. Each panel was carefully disassembled, documented, crated and shipped to a warehouse at Port Hueneme. [See previous articles: Deconstruction of the Dome and The Dome is down.] Then, in July, less than two weeks before the new museum was scheduled to open, Marty, Mattis and Perry arrived to reassemble the top ring of the dome and hoist it into a space specially designed for its display. The men only had two days available to get the job done. “It was another Herculean effort by a lot of people. It was like a South Pole Telescope, IceCube Several active-duty Seabees, as well as a retired Navy master chief, helped with transporting, assembling and lifting the 600-pound crown of the dome into place. Lara Godbille, director of the museum, even helped bolt the panels together. “I think that the dome is going to be one of the most popular pieces in the museum,” Godbille said. “Partially, it’s the mystique of Antarctica and partially, it looks really neat. It’s impressive. It’s big.” On Day 1 of the two-day installation project, the Dome pieces were also very dirty. Nearly four decades of grime, mostly from vehicle exhaust, was caked onto the underside of the panels. The power washer gave way to hand scrubbing with Brillo pads. “We spent a good part of Wednesday shining up the aluminum,” Mattis, 66, said. The next day, the crew had to get creative. How to lift the dome crown off the floor? The ground space was too tight to maneuver the scissors lift. Instead, the team had to drape cargo straps over the ceiling I-beams and use come-alongs to ratchet the piece into the air. A company in nearby Ventura donated the wire rope and other equipment for the installation after learning about the project. “It was just like building the station,” Marty said. “It was the creativity, the passion, the excitement that everybody had to pull it off.”

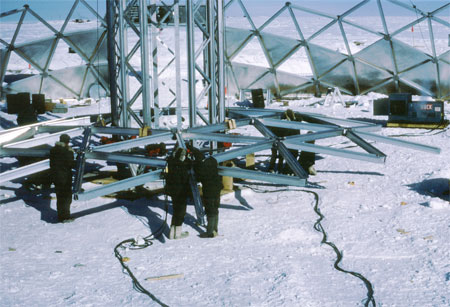

Photo Credit: John Perry/Antarctic Photo Library

Construction of the geodesic dome at the South Pole during the 1972-73 season.

Marty said the last cargo strap was removed at 4:42 p.m. Thursday, July 14. “It completes the desire to bring the dome back to U.S. soil for what [the Seabees] did in that difficult location,” said Marty, 65, who is still interested in finding a home for the rest of the dome, which for now will remain in storage at Port Hueneme. Those two days were the culmination of an eight-years-long effort for Perry. “We’ve been working on trying to get a piece of the dome back for the museum for so many years,” he said. “That was the climax — to got that top section there and put it back together. Assembling it brought back memories of assembling it originally.” Marty hopes to attach an American flag that flew at the South Pole in 2009 on top of the dome. Spectators would be able to see it through the five vent holes in the crown — just as countless Polies did for 33 years. “So when you look up it will be like how you’ve seen it a thousand times before,” Marty said. Godbille said there was a lot of interest in the dome exhibit from the Seabee community that had ventured down to Antarctica between 1955 and 1993. “They’re probably the most vocal group of all of the subgroups in the Seabee community,” she said. “They have been huge proponents of it. They have kept up on it. They will be very happy to know the dome finally made it in.” The dome will be the centerpiece of the Seabee Antarctic exhibit, along with the console from PM-3A, a nuclear power plant that operated at McMurdo Station “It was just a great experience,” Mattis, 66, said. “That’s what makes it worthwhile. We’re doing something that people are interested in and [that] has historical significance and has a story to tell.”

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |