|

Biological pulseWAIS Divide project searches for life in the icePosted October 31, 2008

Outside of penguins and seals that congregate on the continent’s coastal fringes, Antarctica appears to be a lifeless cube of ice, where only humans have the temerity to venture and survive for brief periods of time. But John Priscu In the nearly quarter-century that Priscu has studied biological processes in Antarctica, he and his colleagues have caught glimpses of microbial life where few would think to look — clinging in ice cores drilled en route to Lake Vostok and hiding in the icy lids covering the lakes in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Related Articles

♦ Main Story:

Deep into WAIS Divide ♦ Greenhouse gas: Connecting the pieces ♦ Special Sun package on WAIS 2006-07 “We always thought these ice covers were barriers … and we discovered a whole microbial community living in these ice coverings [over the lakes],” Priscu said. That discovery resulted in a paper in the journal Science in June 1998 Those were discoveries of opportunity. The ice-coring project in West Antarctica promises to be a discovery of intention. “With the WAIS Divide Core project, biology has come in at the planning stages,” Priscu said. Ken Taylor, chief scientist for the WAIS Divide project, said paleoclimatologists are interested in knowing if there is enough biological material in the ice to use it to reconstruct past climate as they use other material such as dust. Also, they want to know: Does the presence of bacteria affect the interpretation of the ice core — do the microorganisms produce gases in the ice that affect measurements of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide or methane? Priscu rattled off even more questions that a concentrated study of biological signals in the ice core may answer. Do more bacteria occur during glacials, long periods of colder climates, or interglacials, shorter warm trends between ice ages? Similarly, are these microorganisms more abundant during times of higher concentrations of carbon dioxide or methane? And just what are the implications to all that? “It’s breaking new ground,” Priscu said. But it’s not just in the ice core where Priscu and colleagues expect to discover life. He and Slawek Tulaczyk, with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at University of California, Santa Cruz, and Mark Skidmore Priscu boldly proclaimed, “The subglacial environment beneath Antarctica is the world’s largest wetland.”

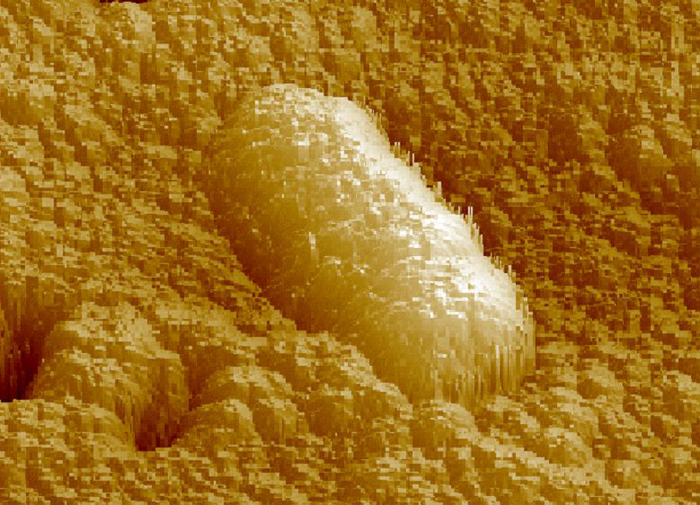

Photo Courtesy: John Priscu

A bacterium found in the Vostok ice core just above the subglacial lake.

It’s in this unknown subglacial world where the ice, bedrock and possibly liquid water intermingle that Priscu and other others believe a unique ecosystem may exist. One not driven by photosynthesis but chemosynthesis. “If it’s all wet, and we know there’s bacteria there, that’s kind of becoming the definition of a wetland,” he explained. “We’re not going to have red-winged blackbirds … and all that good stuff. It’s not that kind of wetland.” Remarked Taylor, “You have this environment that has liquid water in it that has been isolated from the rest of the planet for 10 million years. There’s a lot of interesting biological issues that could be going on with that.” The potential for discovery is big — but so is the potential for contamination, according to Taylor. The current plan is stop drilling about 20 meters above where the ice kisses bedrock unless the project can prove its merit through an environmental assessment. “What NSF does is conduct an Environmental Impact Assessment, in which we view alternatives to achieve the goal of allowing for scientific research while reaching a high standard of environmental stewardship,” explained Polly Penhale, Environmental officer for the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs The project will have to prove that it has the technology to sample the long-dormant subglacial area without risking contamination. “That will have a high bar,” Penhale said. Conceded Taylor, “It’s going to be very difficult to come up with the technology that will allow you to cleanly sample what’s going on down there.” Priscu is more optimistic that the subglacial ecosystem can be sampled without affecting the environment or the experiment. “We don’t want to contaminate the Antarctic environment. We want to be stewards of the environment. Secondly, we don’t want to contaminate the system so our samples are compromised. We don’t want to get samples out of there that are contaminated. It would be a waste of time to study those.” This subglacial lost world would not only provide new information about life on Earth but possibly life on other planets and moons. Scientists often use Antarctica as an analogue for designing intergalactic experiments. An icy ecosystem like that below Antarctica’s ice sheets may hint at what could one day be found on Mars or Jupiter’s frozen moon Europa. “As far as origins of life go, I think icy environments are real important,” Priscu said. Indeed, the veteran polar scientist would argue, “life had a better chance to evolve in cold environments rather than hot, boiling environments.” Some of that proof may sit 3,500 meters below the West Antarctic ice sheet. For now, Priscu’s team will focus on the upper range of ice cores from the WAIS project that arrived this past summer, looking for pulses of life from the deep freeze. “We’re trying to make this a field, a science, but we still have to prove ourselves,” he said. “We still have to go out there and prove it.” NSF funded research in this story: Ken Taylor, Desert Research Institute, Award Nos. 0440817, 0440819, 0230396 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |