Aspiring for knowledgeNew project seeks to learn more about biologically active polynya in remote regionPosted December 3, 2010

In a region famously isolated from the rest of the planet, there are plenty of hard-to-reach places in the Antarctic — crevassed and thinning ice shelves or glaciers squeezing through mountain peaks. And then there are the really remote places to visit — like the Amundsen Sea polynya. Related Articles

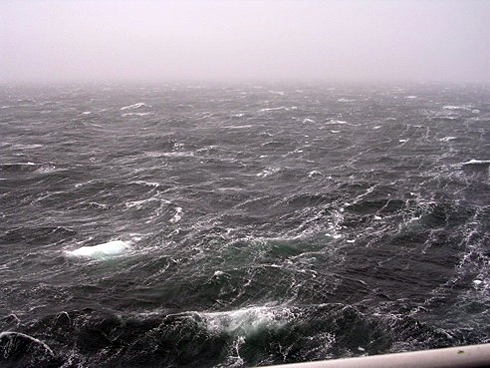

A roughly 38,000-square-kilometer area of ocean initially blown free of sea ice “It’s big enough that when you’re in the middle of it you think you’re in the North Atlantic. It’s grey, overcast, windy, open water. You can’t see any of the ice; you can’t see the ice shelf,” said Patricia Yager But it’s not the remoteness or the size of the polynya, the fourth largest in the Antarctic, that’s drawing Yager and her colleagues to the Amundsen Sea. It turns out that this particular polynya is a biological oasis, boasting the highest primary productivity of any similar region. A polynya is a seasonally recurring pool in the sea ice caused by either winds (latent heat polynya) or ocean heat from below (sensible heat polynya). The absence of ice fosters a strong exchange of heat, moisture, and gases between the ocean and air, which has implications for global ocean circulation and carbon cycling. [See previous article: Pulse on polynyas.] It’s also an area of intense phytoplankton “[The Amundsen Sea polynya] is a very dynamic place that we don’t know much about,” said Yager, associate professor of marine sciences at the University of Georgia A few measurements were made in 2007, when the Swedish icebreaker Oden Now American and Swedish scientists will return to the polynya aboard the USAP research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer Yager said the research team hopes to spend about three weeks in the open waters of the Amundsen Sea polynya to collect data that will help them better understand what’s happening to this climate-sensitive ecosystem. The first and foremost question the scientists want to answer: What is driving the high productivity, which is about double that of other polynyas? Phytoplankton growth depends on the availability of carbon dioxide, sunlight and nutrients. They also require trace amounts of iron, which caps their growth in the iron-limited Southern Ocean. Yet the chlorophyll concentrations in the Amundsen Sea polynya are so high that the greenish coloration from a bloom in the water can be seen from satellites in space. One factor in the high productivity, as well as the wild swings in interannual variability, could be the nearby Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers just to the east, according to Kevin Arrigo Pine Island and Thwaites are among the fastest moving glaciers in Antarctica, feeding ice into the Amundsen Sea. During a 2009 science cruise to the nearby Pine Island polynya, Arrigo and colleagues made a handful of chance measurements that implied the rivers of ice were dumping iron into the polynya. “We found that there was so much iron being released that it actually draws down all of the other nutrients to zero, which is something you almost never see in the Antarctic,” Arrigo said. “The reason it’s important is because if you can drawn these [other nutrients] down to zero, it becomes a very important sink for CO2.”1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |