Penguins of a featherSeries of fossil discoveries sheds light on evolution of iconic seabirdPosted January 21, 2011

A team of paleontologists headed to a string of wind-blown islands off the Antarctic Peninsula this austral summer don’t quite know what fossils they might find. They’ll look for evidence that Antarctica was once a sort of superhighway on which mammals once traversed between South American and Australia when the continents were linked together. Or perhaps they’ll discover further proof that at least some lineages of modern birds evolved before dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago. Related Articles

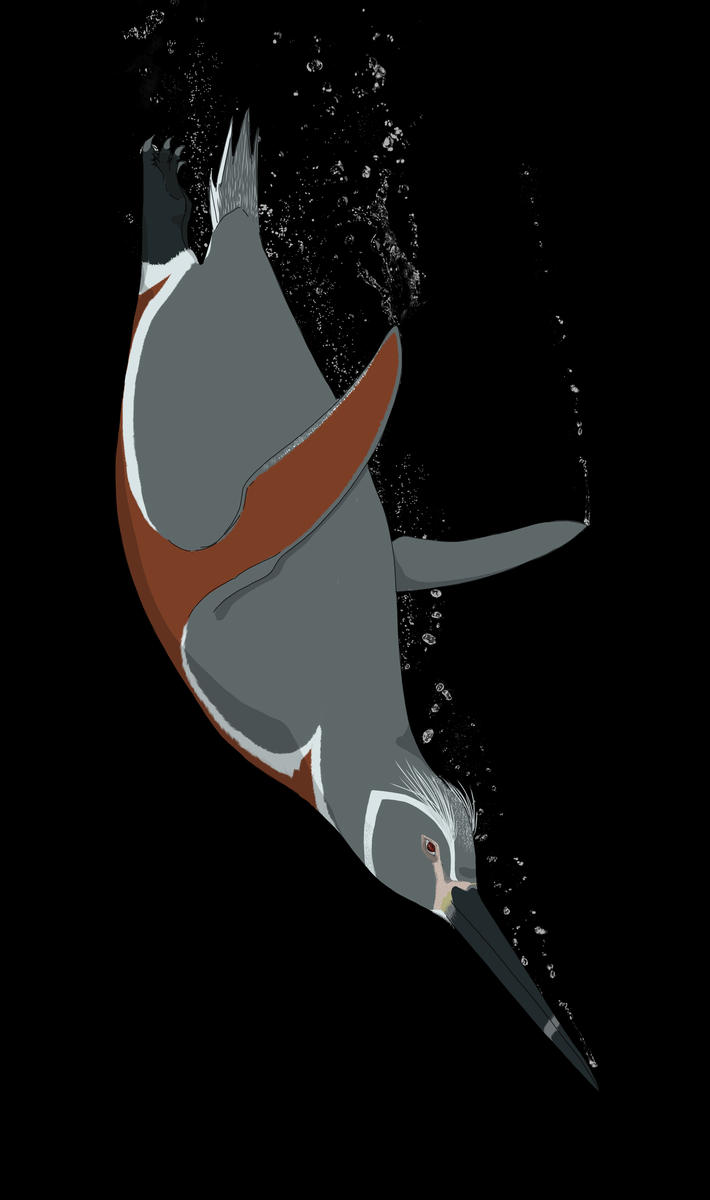

And they’ll be just as happy to find some good-old-fashioned dinosaur bones on islands like Vega and Seymour that have proved to be valuable windows into the evolution of life millions of years ago. Julia Clarke “It’s certainly not out of the realm of the possible that we could discover Cretaceous relatives of penguins,” said Clarke, a member of the paleontology team lead by Ross MacPhee Today’s body of evidence points to a high-latitude origin for penguins (Order Sphenisciformes). Fossils from Antarctica and New Zealand date from the Paleocene, right after the Cretaceous. Over the last decade, Clarke and colleagues have announced a series of discoveries concerning the evolution of penguins. The most recent, published in the online edition of the journal Science on Sept. 30, concerned a 36-million-year-old fossil from Peru with preserved evidence of scales and feathers. The new species, Inkayacu paracasensis, or Water King, was about 1.5 meters long or about twice the size of an emperor penguin, the largest living penguin today. The fossil shows the feathers were reddish brown and grey, distinct from the black-and-white coloring of today’s living penguins. “Before this fossil, we had no evidence about the feathers, colors and flipper shapes of ancient penguins. We had questions and this was our first chance to start answering them,” Clarke said in a previous press release. The fossil shows the flipper and feather shapes that make penguins such powerful swimmers evolved early, while the color patterning of living penguins is likely a much more recent innovation. In 2007, Clark and colleagues reported finding two new penguin species in Peru. The fossil discoveries showed that penguins reached the equatorial regions about 30 million years earlier than expected and during a period when the Earth was much warmer than it is now. And in 2003, Clarke was part of a team that reported fossilized bones found in Tierra del Fuego in Argentina are likely those of the earliest known South American penguin, which at the time doubled the fossil record of penguins on that continent. In the big picture of penguin evolution, Clarke said, the different physical characteristics suggest different ecologies between ancient and modern penguins. For example, Inkayacu paracasensis also possessed hyper-elongated beaks. “They would presumably be hunting in a slightly different way. We do wonder if potential differences in the color patterns of early penguins could also be related to these differing ecologies.” Clarke said. In the even bigger picture of overall bird evolution, the recent find emphasizes that numerous evolutionary shifts were happening at the end of the Cretaceous period and across the Cenozoic era. Are the changes related to even comparatively recent global events, such as the cooling of Antarctica that began about 40 to 35 million years ago? “There are so many questions we could answer with new fossil data from Cretaceous sites in Antarctica. I hope we get a chance to try and answer them,” Clarke said. NSF-funded research in this story: Julia Clarke, University of Texas at Austin, Award Nos. 0927341, 0408308, 0731404

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |