|

Page 2/3 - Posted February 10, 2012

Now, in addition to tagging newly born pups in the early Antarctic summer, researchers weigh pups as closely as they can to the day after birth, at 20 days of age and at 35 days of age, when they’re nearly weaned from their mothers. Only pups with mothers that have known life histories are weighed, Garrott said. “We know everything about the mom, and we can use her attributes that we know, because she’s been tagged since she was a pup, to see how that influences the mass of the pup,” he explained. More Info

Be sure to check out the research team's education and outreach website, Weddell Seal Science

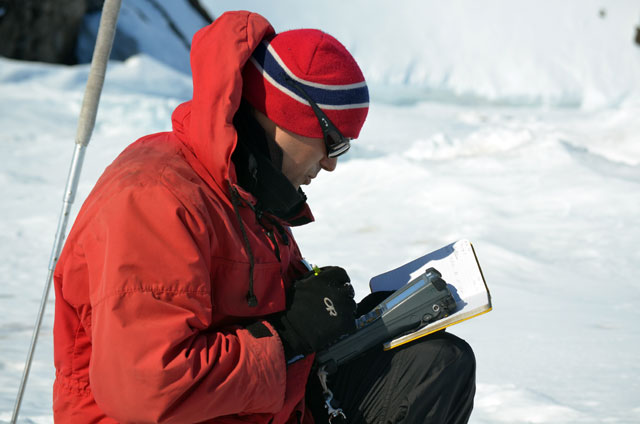

Sidebar article — Getting techie: Weddell seal population dynamics study employs different technologies The life history includes not just a Weddell seal mom’s age, but also her mass from year to year and the number of pups that she has produced. Garrott said the team is able to indirectly measure how resource-rich the region is each season — if there are lots of fish to eat — based on how “fat and happy” the pups are that year. A bigger pup, something in neighborhood of 130 kilograms, is more likely to survive. And a large pup birthed in a generally successful year for everyone — like the last two seasons, which have each seen more than 600 newborns against an average of about 400 — has an even better chance to grow to maturity. Still, chances of survival are grim. Only 20 percent of tagged pups ever show up at the colony again. Many probably end up as prey to orcas and leopard seals. Some may just be poor foragers and starve to death. All that data have given rise to the hypothesis of what Garrott calls the “supermom,” individuals that live longer and produce more pups than other Weddell seals. Similar to a theory put forth by seabird researcher David Ainley “We have tremendous variability in individuals for how many pups they produce in their lifetime,” Garrott said. “Some of it is probably genes; some of it is luck for the kind of year that you were born, and several other mechanisms, so we try to tease out all of those things through these studies as well.” The generally docile behavior of what scientists call an apex, or top, predator like the Weddell seal makes it an easy animal for the scientists to handle, especially when they need to weigh pups. That makes Chambert and DeVoe’s job a bit easier as they move among the seals at Hutton Cliffs, checking tags on back flippers against their records. They find one particularly plump fellow who hasn’t been on the scale for its third and final weigh-in. The pair of young researchers fit the pup into a heavy-duty blue canvas bag, which they suspend from a scale that they hoist upon their shoulders. The whole operation takes about two minutes, and the freed pup squirms back toward its mother. “This is the best animal in the world to work with for this kind of study,” said DeVoe, who has also assisted Garrott on a similar population dynamics study in Yellowstone National Park “The exact same processes that we’re studying here in this Antarctic marine system are the same processes that I’m studying in Yellowstone National Park in a terrestrial system” Garrott noted. Even the abiotic environmental factors are similar. In McMurdo Sound, sea ice plays a key role in driving the marine environment from the bottom up, from serving as a habitat for microorganisms to a platform for seal breeding. In Yellowstone, winter snowpack is a key abiotic, or nonliving, factor in the environment that affects the ecosystem. “Our combined understanding of looking at the same processes in different systems helps allow us to make generalizations about those ecological process anywhere, whether it’s one we’ve studied or not,” Garrott said. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsNational Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |