Deep core completeWAIS Divide project finishes five-year effort to retrieve 3,331 meters of icePosted January 31, 2011

More than 20 years in the planning. Storms often prevented planes from arriving for days or more at a time. In the final weeks, mechanical breakdowns of the drill and the usual weather delays appeared to derail any hopes of reaching the final depth goal for the season of 3,330 meters. But it happened. It is done. The U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) The core — drilled at a location dubbed WAIS Divide, a high point on the ice sheet where the ice begins to flow in different directions, akin to the Continental Divide in the United States — is the second-longest ice core ever recovered anywhere. The Russians have the record for the deepest ice core, which they drilled in the 1990s at Vostok Station in East Antarctica, to a depth of 3,701 meters. The previous U.S. record was in Greenland, when scientists reached 3,053 meters on July 1, 1993. “Not only is this the deepest ice core ever drilled by the U.S., but the fact that we have reached our target depth for this season means that the project is on track to be able to complete the entire … project schedule,” said Julie Palais, program manager for Antarctic Glaciology in the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs “It is wonderful to see everything coming together so nicely. ... It is gratifying for me as the program manager, but also for everyone who has been involved because I know how much work has gone into making it happen,” Palais added.

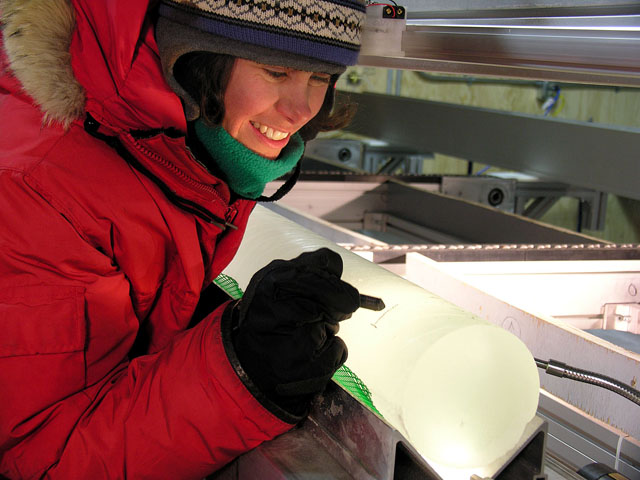

Photo Credit: Mark Twickler

Scientist Gifford Wong samples for water isotopes in a section of ice core.

For scientists who will spend the next years, if not decades, analyzing various properties of the ice to understand past climatic and environmental conditions, depth is less important than the timescale represented by the core. “We did not come here to study the climate of Antarctica — we are here because this is where the information is stored,” said Kendrick Taylor The last 100,000 years covers the most recent glacial period, when the Earth was cooler, and large ice sheets covered the northern and southern hemispheres. Concentrations of the main greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) were much lower than today’s high of 390 parts per million. In fact, based on other ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland, scientists are convinced CO2 levels are the highest they’ve been in at least the last 800,000 years. Climate scientists are particularly excited about the WAIS Divide ice core because it promises to offer a particularly “high-resolution” record of the past 40,000 years, with thick annual layers akin to tree rings. “It is the most detailed record from Antarctica covering a long time period,” said Ed Brook Thanks to the region’s high snowfall rate, there is more ice and more air per year in the core than any other previously collected core. That means scientists can analyze the core in detail, in some cases seeing how year-to-year climate changes unfold. “That kind of data is critical for understanding how and why climate changes,” Brook explained.1 2 3 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |