|

SPICE-ing it upNew project plans to retrieve South Pole ice core beginning in 2014-15Posted March 8, 2013

Glaciologists plan to SPICE things up at the South Pole. Most researchers head to the research station at the bottom of the world for studies related to astro- and particle physics. The South Pole Station One team of scientists is more interested in the thick ice sheet upon which the station sits. The South Pole Ice Core (SPICE) “It really is a blank spot on the map. I think we’re really going to learn a lot from this core,” said Eric Steig An ice core is something of a time machine for Earth’s past climate and environmental conditions. Scientists can analyze bubbles of various gases trapped in the ice to get a sample of the ancient atmosphere. Dust and chemicals found in the ice can also provide details about past temperature and climate. SPICE is targeting a timeline 40,000 years back into the past as part of an initiative called International Partnerships in Ice Core Sciences (IPICS) The target of 40,000 years spans the transition from the peak of the last glacial period when ice sheets were at their maximum extent — referred to as the Last Glacial Maximum — to the present warm period called an interglacial. A series of abrupt climate changes also occurred during those 40 millennia, so another reason scientists are interested in studying ice cores is to learn more about such events in order to predict future climate patterns and variability. “[South Pole] will be the highest resolution East Antarctica ice core recovered,” said Eric Saltzman Saltzman said a 1500-meter-deep ice core from the South Pole should offer relatively well-ordered stratigraphy, meaning the layers are well defined and the youngest layers are on top and the oldest layers are on the bottom, with no evidence of folding or faulting in between.

Photo Credit: Devon Stross/Antarctic Photo Library

A sundog at South Pole. The geographic marker is at the far right.

However, the eventual analysis of the ice core’s properties will have to account for the fact that the ice originates from a region up to 400 kilometers away. The surface of the ice sheet at the geographic South Pole flows about 10 meters per year. In addition to the stratigraphy, the very cold temperatures and relatively low impurity levels at the South Pole make the SPICE core ideal for trace gas measurements, according to Joe Souney “One our primary motivations for collecting an ice core from the South Pole is that it will provide us with one of the best trace gas records possible,” he said. “This is because of the very cold temps and low impurity levels at the South Pole … enabling us to measure gases with very low concentrations with more accuracy and precision.” The logistical support offered by the research station, located at a total elevation of about 2,800 meters, is also a strong argument for drilling the U.S. Antarctic Program’s The SPICE project follows on the heels of a nearly decade-long effort to recover an ice core from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) on the divide where the ice flows in different directions, sort of like the Continental Divide in the United States. WAIS Divide

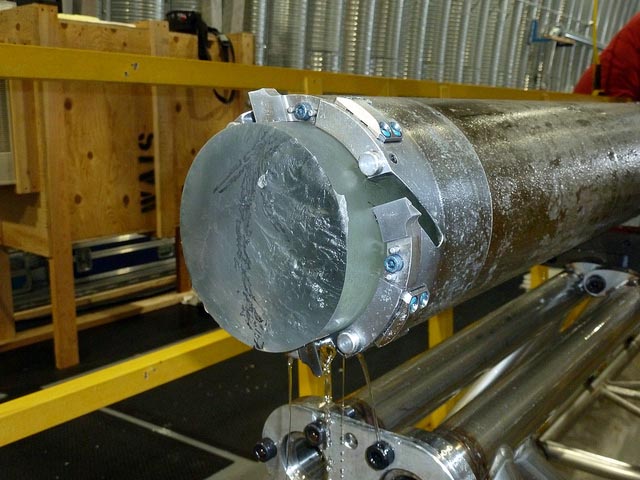

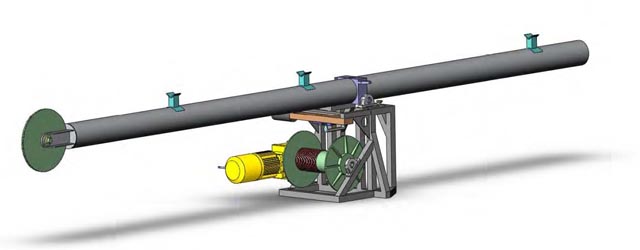

Photo Credit: IDDO/University of Wisconsin-Madison

Graphic of the new drill in development for the SPICE project.

After eight years of preparing for drilling, and collecting the main and replicate cores, it will take another two field seasons to measure various properties of the borehole (called borehole logging) and remove the WAIS Divide field camp. The SPICE project timeline is relatively short in comparison. The schedule calls for two drill seasons, beginning in the summer of 2014-15. The exact location of the South Pole borehole is still to be determined. That was one of the reasons behind the February workshop in Boulder. The schedule does present some challenges, particularly regarding a zone of the proposed core called brittle ice. The air bubbles in brittle ice are so compressed that pressure is intense enough to shatter the core once it reaches the surface. T.J. Fudge “It is an inexact science figuring out where brittle ice occurs,” Fudge said. The brittle ice, based on the initial estimates on the age-depth ratio of the ice sheet, would likely overlap with the last glacial maximum and the beginning of the current interglacial known as the Holocene, a time period between 26,500 and 10,000 years ago. Jeff Severinghaus at Scripps Institution of Oceanography “Ice becomes as strong as steel at minus 100 degrees,” Severinghaus noted. SPICE will employ a smaller, more mobile drill than the one used for the WAIS Divide project. Dubbed the Intermediate-Depth Drill (IDD) The Ice Drilling Design and Operations (IDDO) “We’re trying to develop a smaller-scale capability for the [ice-drilling] community,” Saltzman noted. NSF-funded research in this story: Eric Saltzman and Murat Aydin, University of California-Irvine, Award No. 1142517 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |