|

Type C personality'Ross Sea' killer whale one of several species found around AntarcticaPosted May 24, 2013

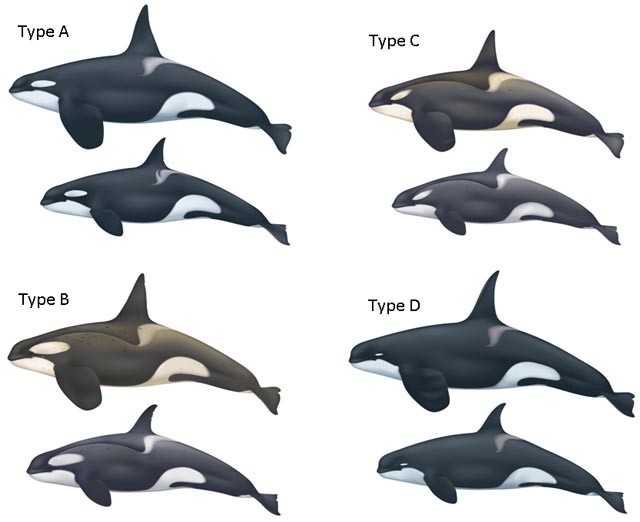

If Captain Ahab of Moby Dick literary fame had been a scientist, it might have been an orca and not a sperm whale that drove him to madness. Not because of some antagonistic relationship, but because Orcinus orca has proven to be a tricky animal to study. That’s been particularly true because not everyone agrees on how many species of killer whales even exist. Robert Pitman Pitman and colleague John Durban The project, which involves tagging both killer and minke whales with satellite transmitters to track their movements, also offered an opportunity to collect biological samples from the animals. The biopsies can provide information about the animal’s diet, as well as genetic samples that will bolster the evidence to classify the orcas into separate species. There is still some controversy and resistance to the idea of multiple killer whale species, according to Pitman. However, even before the genetic evidence, scientists had noted differences in physiology and behavior, particularly the feeding preferences among three types of orcas found in the Antarctic. Type A is the sort of prototypical killer whale, with a medium-sized eye patch. Its preferred prey is the Antarctic minke whale. Type B killer whales, with a white eye patch twice the size of the Type A species, are believed to prey primarily on seals. Finally, Type C, the smallest of the trio, has a small eye patch that slants forward (the other two are parallel to the body). It chases fish, and has been known to prey on the large, long-lived Antarctic toothfish. “It’s fun working with different kinds of killer whales and seeing how different they are,” Pitman said during an interview at McMurdo Station last December. Later, in February of this year, he and Durban also worked aboard a small research vessel around the Antarctic Peninsula, where Type B seems most prevalent. In contrast, fish-eating Type C appears to favor the Ross Sea region near McMurdo Station. That’s also the area of the Southern Ocean where a commercial fishery that targets Antarctic toothfish operates. The NOAA researchers said they believe it’s important to quantify the Ross Sea population, particularly if Type C is in direct competition with the commercial fishery for Antarctic toothfish. They photograph each whale, which will help them to identify individuals and estimate the number of killer whales in the region. “We need to know not just what they’re feeding on, but how many are here,” Pitman explained. Durban said that based on popular media programming — what he calls the BBC effect, referring to documentary series like Frozen Planet — it’s tempting to believe that there are plenty of killer whales. “It’s really important to get a handle on individuals,” he said. Killer whales are not believed to be a threatened species, though Type C orcas may not be faring as well as their cousins because their preferred prey is also popular on dinner plates around the world. In contrast, Type B killer whales, which hunt protected mammals, are probably doing better, according to Durban. In addition to the three types of true Antarctic killer whales, Pitman said he believes there is a fourth subantarctic species, Type D, which has proven to be somewhat elusive. Evidence so far relies on observations dating back to a 1955 mass stranding in New Zealand, along with a half-dozen sightings at sea over the last 10 years. In February 2011, Pitman, Durban and colleagues published a paper in the journal Polar Biology that described the fourth Southern Hemisphere killer whale type. Its diet remains a mystery, through researchers believe it too many be a fish-eater that preys on Patagonia toothfish, a cousin of the Antarctic toothfish, which is found in the Ross Sea on the other side of the continent. However, Type D doesn’t seem equipped to live south of 60 degrees. “I think that shows how important that barrier is physiologically,” Pitman said. “You have to be a different kind of killer whale to come down here and live.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |