|

Science goes to new heightsThompson travels where few dare to retrieve ice core recordPosted June 27, 2008

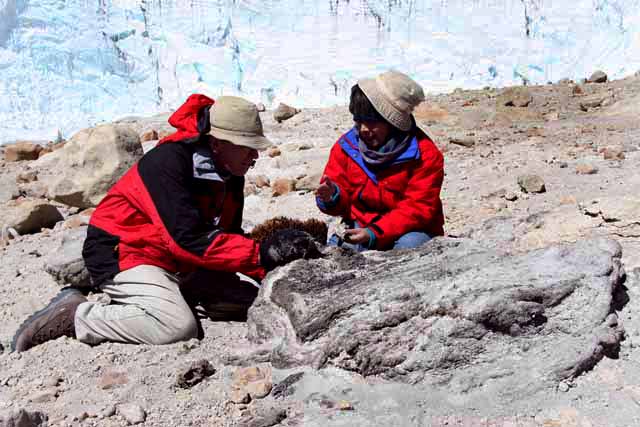

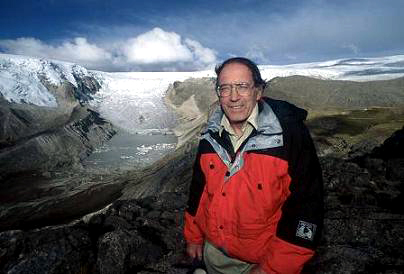

It seems there’s little that Lonnie Thompson and his team of scientists and drillers haven’t tried in their quest to retrieve ice cores from high-altitude, tropical regions around the world. A natural storyteller, Thompson spins tales of alpaca sacrifices at remote villages and abandoned hot air balloon adventures to the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro, scarcely needing journalistic prompts from his inquisitor. He’s well practiced at these sorts of interviews; his exploits a natural magnet for the armchair traveler. He’s made more than 50 science expeditions to some 15 countries over the last 30-odd years. He solidified his reputation earlier this decade after warning that Kilimanjaro would permanently lose its frosty cap by 2020, if not earlier. Yet Thompson, a paleoglaciologist at Ohio State University’s Byrd Polar Research Center “It’s a blessing and a curse, and much of it is unwarranted because it’s really a team effort,” he says when asked about the fame that he’s achieved. But perhaps it’s not so unusual given his team’s mission: to recover the climatic history stored in the world’s vanishing ice fields between 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south latitude. “I would never have guessed [it possible] 32 years ago if somebody had told me that I would still be looking at ice at my age. I’d say, ‘You’re crazy, because who’s going to fund it and how can it be important?’” muses Thompson, who turns 60 in July. “[Ice core science has] gone from being a boutique type of subject when I was a student to being center stage because of the potential impacts of sea level.” Ice cores contain a wealth of information about past climate. Scientists can analyze the bubbles of gas trapped inside the ice to determine how much carbon dioxide, for instance, was in the atmosphere in the past. That’s how we know that current levels of CO2 — nearly 390 parts per million now — haven’t been this high in some 800,000 years, the extent of the current ice core record. Dust in the cores can reveal other information about climate, such as wind conditions. Thompson, quoting Ernest Shackleton, whose ship was trapped and eventually crushed in sea ice during Antarctica’s Heroic Age of Exploration, notes, “‘What the ice gets, the ice keeps.’ … Ice will archive anything that gets trapped by it.” And it’s the archive in the tropics that particularly interests Thompson, though his first polar fieldwork in the 1970s as a graduate student at OSU “I really like the mountain ranges,” he explains. “You can look out from your drill site and you can see the Amazon Basin or the ocean. And where we work, you’re always working in a different culture.” But it’s not really for the aesthetics that he and his colleagues regularly climb and drill into ice above 5,500 meters (more than 18,000 feet), where Thompson has reputedly spent more time above the so-called death zone than anyone on the planet. He observes that about 70 percent of the world’s 6.7 billion people (and counting) live just 30 degrees north and south of the equator. “It’s an area where you need to understand natural climate variability, as well as potential human impacts on that,” he says. The ice, like Thompson, has many stories to tell. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |